What’s it like for a young woman artist trying to make her way in the artworld of today? Bella Chidlow is a recent art school graduate interning with the SHEILA Foundation. Here she talks about her experiences, her work and the central role of social media for young artists – viewed through the life and work of an artist who inspires her, American photographer Francesca Woodman.

My name is Bella, I am 22 and part of a generation of young female artists currently trying to get our work ‘out there’. We are born at a crucial time; with the development of the internet, the world is more connected than ever before. We have grown up with technology and are watching it expand into a plethora of career paths and opportunities. I am learning that connectedness breeds growth and that the digital world has space for everyone.

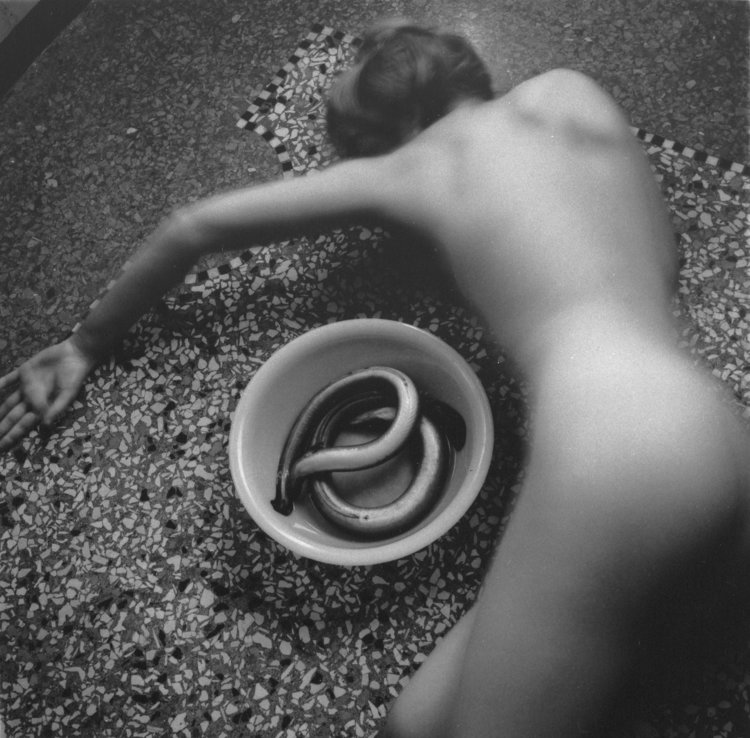

Francesca Woodman, From Eel Series, Venice, Italy 1978, Gelatin silver estate print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, © Charles Woodman, Courtesy Charles Woodman, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

I began working with the SHEILA Foundation in May 2018. As an artist and feminist I have always been naturally drawn to art by women, so learning more about this world was appealing. My first job was to carry out a gender count of the male and female artists in the 20thcentury rooms at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. I was expecting some disparity but the bias was shocking, and a reminder of why SHEILA is necessary. It also painted a bleak picture of the art world I am trying to break into – as a young female artist it is concerning to say the least!

It seemed glaringly evident that there was a great deal of female expression not being heard, or rather seen. Their voices, their perspectives, are still not considered a priority. It helped me understand that art history has and mostly still does operate within a narrow, patriarchal scope, and that in order to find the female artists I know lived and worked I must search outside the traditional institutions. One such artist captured my attention instantly; American photographer Francesca Woodman.

I was recently acquainted with her work through the book Francesca Woodman (The Roman Years Between Flesh and Film(2012) by Isabella Pedicini. It revealed she was a prolific creator of about 10,000 negatives and 800 prints before ending her life at 22. She presented a considered moment of vulnerability in each shot, mostly naked portraits of herself or her friends. In her self-portraits she inhabits the roles of both artist and muse, reclaiming the gaze and directing it towards not only herself but the space around her, the world she has carefully created.

On discovering Woodman I felt a strong kinship with her, and recognized in myself her need to present herself to the world in a way that feels authentic. It is not difficult to identify parallels between her obsession with self-portrayal and today’s selfie culture of social media users everywhere.

When I walk around this world I can sometimes feel the collective, possessive eye boring into me. I feel it when cars slow down next to me, when men stop talking and start nudging as I walk past, any time I enter a space and those curious eyes lock onto me and don’t let go. It bothers me more than most, and my defense tactic, just like Manet’s Olympia, is to use my own gaze to catch them. It fuels my connection with the generations of pissed off women artists before me.

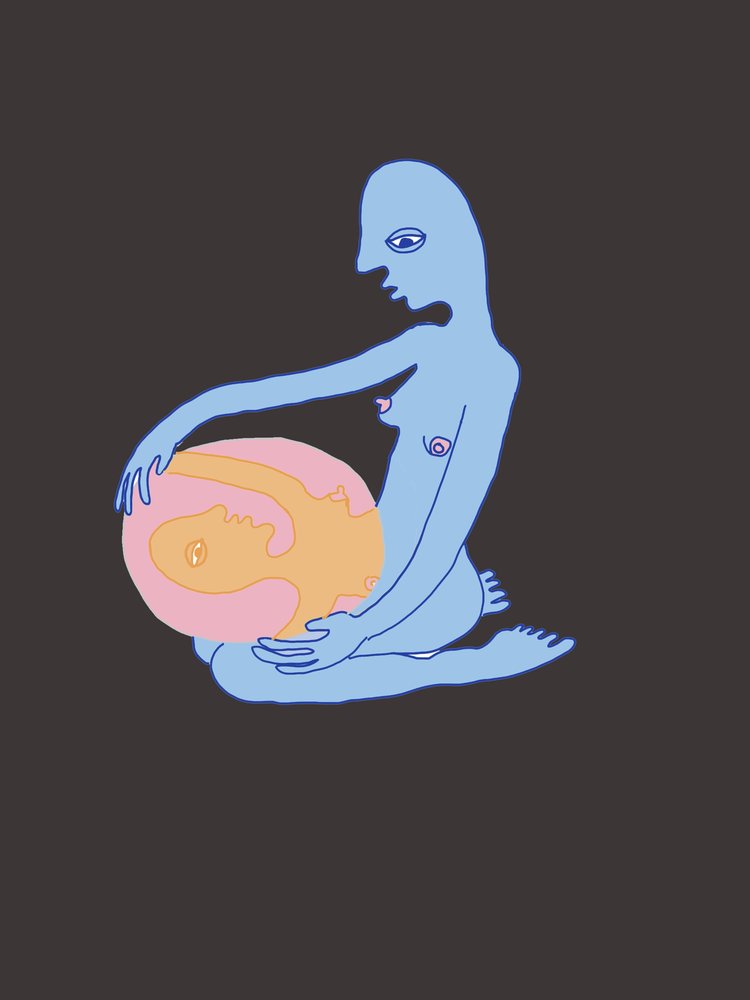

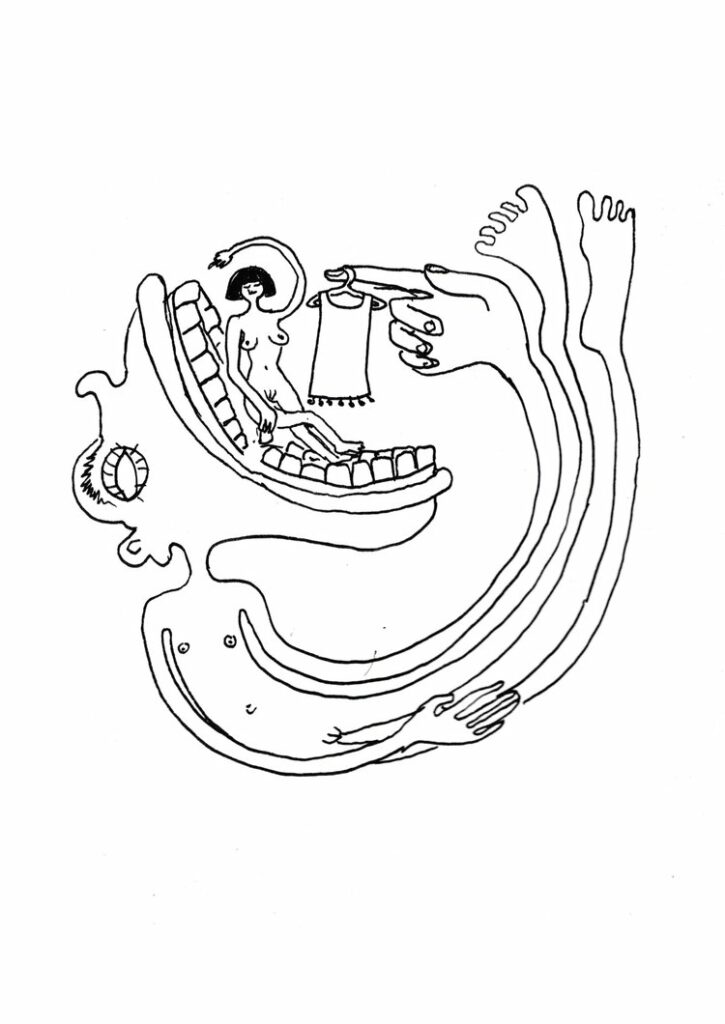

Bella Chidlow, Collecting the male gaze 2018, digital illustration, 59.4 x 42 cm.

I feel strongly that Francesca Woodman had similar frustrations with how she was being viewed in the world she lived and worked in; 1970s-80s New York and Italy. “Woodman was not motivated by narcissism, but by an obsessive need to affirm her identity. In even her earliest photographs, we can perceive her constant, penetrating self-examination.” (Pedicini 2012)

Indeed, her work was a direct action to grasp hold of the male gaze, a need to create new versions and realities of herself. Like anyone, but especially as a young woman, I can relate to her attempts to create a world in which she is free from the projections and expectations of an ultimately patriarchal society.

I think I use art making as a defense for the fact I am always being watched, and it is never with permission. Although each person has their vocation and must try to serve that, I cannot discount my discomfort at being looked at as a motivator for making something for people to look at. It boils down to deflection; it is an attempt to get them to stop looking at me. More than a distraction, it is shifting the focus and scrutiny to something I can take credit for, something my mind manifested rather than the body it resides in. It is about making space for myself in the universe.

In my work I attempt to create a world in which I am freed from scrutiny, where the body looks how it feels to me, loopy and fluid. Almost every portrait I’ve ever drawn has been bald, sidestepping all of the cultural weight hair holds. I do not want them to be defined by the external, and nothing is more external than hair.

The majority of students in my BCA were female, but having graduated last semester a large proportion are already pursuing non-art related careers. Of those who’ve stayed with art, the ones aiming for gallery shows are an even smaller group. I’ve observed that those who post art on social media are far more motivated to make work and maintain the account rather than those creating to fill the marking criteria. We are all attempting to navigate this new digital landscape together and as the image of what a successful artist looks like shifts, the playing field is leveled and the opinion of our educators often fades in comparison to those of our followers. It is undeniable that knowing how to navigate social media is an asset as we enter the workforce.

Bella Chidlow, Reflection 2018, digital illustration, 59.4 x 42 cm.

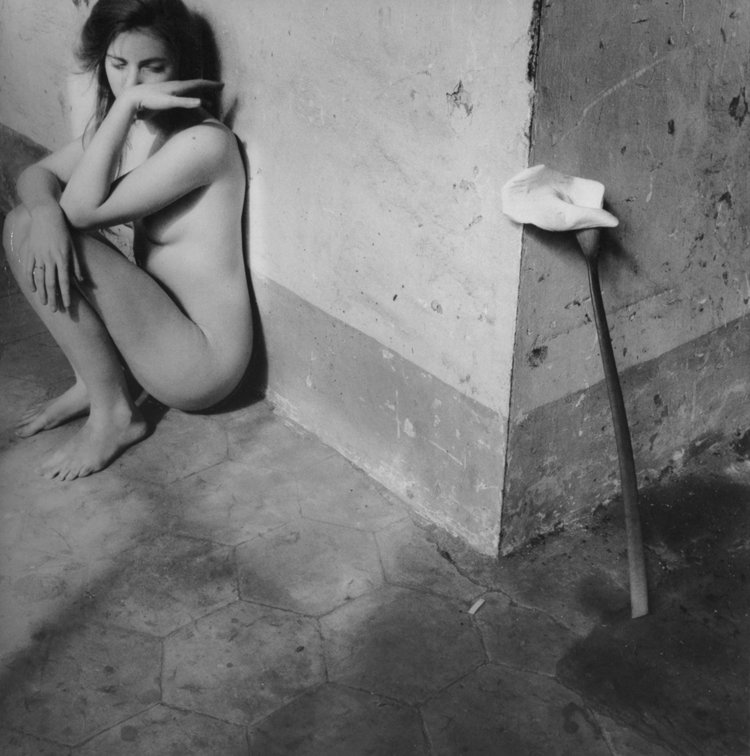

The iPhone has ensured that photography is part of our everyday life, and to flip the camera to yourself is a feature that seems natural. In the 1970s, a self-portrait was a more difficult feat – but most of what Francesca Woodman produced featured herself.

Pedicini details Woodman’s wry but pragmatic sense of humour; upon being asked why she mostly photographed herself she said: “It’s a matter of convenience, I photograph myself because I’m always available”.

It echoes the famous quote by Frida Kahlo: “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best”. The two artists share themes of introspection and an obsession with self-portraiture that presents them as both vulnerable and elevated. Both artists are loved by feminists for living an honest expression of their womanhood in their short lives. They were both significantly influenced by Surrealism; Woodman’s interest in particular ensured that her “imagery was primarily about myth and dreams, but her pictures opposed and undercut the overwhelming misogynistic tone of the original Surrealist movement, their implicit critique thus establishing her thoroughly postmodern street-cred”. (Pedicini 2012)

“I want my photographs to condense experience into small images that contain all the mystery of fear or whatever it is that’s latent in the eyes of the viewer, and bring it out as though it were her own experience”.

Letter from Francesca Woodman to Edith Schloss, 1980.

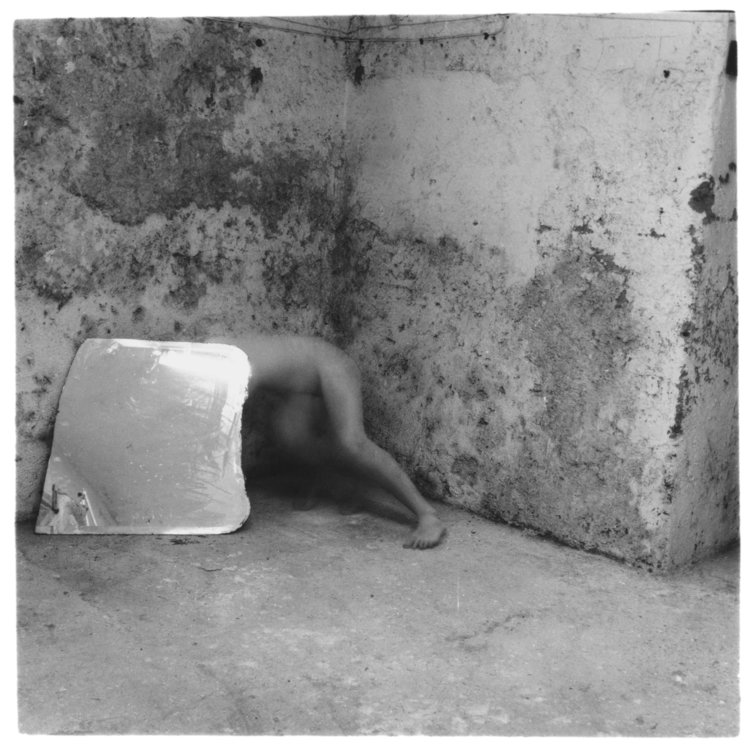

Francesca Woodman, Self-deceit #5, Rome, Italy 1978, Gelatin silver estate print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, © Charles Woodman, Courtesy Charles Woodman, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

There is no question that Woodman’s photographs have the maturity and self-awareness of someone far beyond her years. It seems that this was her personal burden as well as her artistic gift. Pedicini explains that “she borrowed the idea of integrity from objective photography and unaltered photographs – reality without artifice – but she applied this technique to a ‘subjective’ kind of photography, detached from the world around her, focusing instead upon the private, personal dimension, her own body, and her own emotions.” This is the intriguing element present in all of her work, this sense that you are looking at a vulnerable and beautiful body but also the creator of the world in the photograph; every inch of it is considered and applied by Woodman before jumping, naked, into the frame.

Her work’s strength lies in its “very intermediacy, its shifting perspectives and moods, its concerns with identity and persona” (Pedicini 2012). She created a prolific amount of work, most, self-portraits that each exposed a slightly different side of herself. Her work encompasses the self portrait, and “the coincidence of subject and object as a study of the feminine, and projects the psychic dimensions of the artist who chooses her own body as the fundamental object of her art”. (Pedicini 2012)

Although the photographs are clearly staged, it feels that we are peering into the intimate moments of her alone time – like the viewer has caught her playing a weird game with herself. This is another element of Woodman’s work that women especially connect with, this introspective conversation you have with yourself in your ‘me-time’. Pedicini affirms this:

‘We cannot exactly differentiate between Francesca the person and Francesca the character. Her self-portraits confirm this, as the artist endlessly adopted and repeated this inward-focused study, a study in which we participate, but which is addressed in the first instance to her own reflection.’

Francesca Woodman, Self Portrait, Easter, Rome 1978, Gelatin silver estate print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, © Charles Woodman, Courtesy Charles Woodman, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

The experimental nature of Woodman’s approach to photography means that she produced a variety that “indeed serves the continuous, private development of her self…. Woodman places herself completely nude before her own gaze, and before us, too”. (Pedicini 2012) In many of her portraits, the face or figure is blurred, making the subject unrecognizable and elusive, a technique which “opens the door for doubt and for that vital movement which photography necessarily, by its nature, must freeze”. (Pedicini 2012)

Her blurred figures echo the ghostly images of Victorian spirit photography, and she certainly considered themes of her own mortality in her work. Francesca had struggled with depression since she moved to New York in 1979 and her work was ignored by all of the cultural magazines she sent them to. In addition to this, her grant application was rejected by the National Endowment for the Arts. In the autumn of 1980, Francesca attempted suicide but survived, and following this received psychiatric treatment and moved in with her parents. As they were both working artists, this only made success seem more critical for he, and she was haunted by a constant sense of inadequacy; she held herself to harsher standards and felt that her career wasn’t progressing fast enough. On January 19, 1981, following the end of a romantic relationship, Francesca Woodman jumped to her death from the loft window of a building on the Lower East Side.

I cannot help but imagine Francesca’s life if it had existed today, with all the resources available to us. I can picture how her career would have blossomed through social media, how having a clear channel to stream her work into the world would have gained her both supporters and opportunities. Obviously no amount of ‘likes’ can make one accept themselves but people appreciating her work daily would have served as a (needed) reminder that she was on the right track. At that point in her career, when visibility is paramount, the viral power of the internet would have been an incredible asset.

In its eight years of (virtual) existence, Instagram has become “an indispensable, all purpose-tool for everything art related. Emerging artists have used it to establish themselves and find collectors, and high-flying art-market stars are embracing it as well, in diverse ways.” (Kino 2018). As Olivia Fleming explains in ‘Why the world’s most talked-about new art dealer is Instagram’ (Vogue 2014), “artists use Instagram as their own virtual art gallery, playing both dealer and curator while their fans become critics and collectors, witnessing the creative process in real time”. The direct nature of Instagram means that artists can sidestep the traditional route of attempting to get galleries’ attention and connect with their buyers candidly.

Francesca Woodman, November has been a slightly uncomfortable baroque 1977-78 Gelatin silver estate print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, © Charles Woodman, Courtesy Charles Woodman, and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

My main channel for getting my work out there, like most of my peers, is Instagram. I created a separate art Instagram because I was unsure about showing my art to all my regular followers and I wanted people to see it for what it was, not with photos of the woman that made it. I feel the addictive pull of Instagram, but I use it to motivate me to make work better and more often. Social media undoubtedly dominates our culture and impacts our collective psyche. Growing up with it means my peers and I are less likely to question its necessity in our everyday lives. Although you can learn to limit and manage your social media use, there is a definite sense that there’s no going back from here.

Aside from commerce, Instagram as a whole is saturated with photos people have taken of themselves. It offers anyone the opportunity to present themselves; as the subject, photographer, editor and caption writer of their self-portrait. Women of all body types can share them with the world without the restrictions of modeling or magazine standards, and creating a more diverse representation of the average body can only be encouraging from a feminist perspective. In turning the camera to her own body, a woman reclaims the narrative prescribed to it. And posting it to the internet is a validation of self-confidence which is subsequently confirmed by others.

It is also a platform for successful artists to remain connected to their viewers; for example Cindy Sherman has a public Instagram account and regularly shares bizarre self-portraits altered with airbrushing apps like Facetune. These images are designed for Instagram alone; as she has explained their quality ‘really isn’t going to hold up for a blow-up of a photograph’. She is selling work at auctions for nearly $US4 million but regularly gives these images to the public for free.

The future of Instagram is bright and diverse, because it reflects the nature of its users, the public. I hope that current and future artists will be able to use it as leverage, that it emboldens them to create work free from the constrictions of traditional galleries and directly for their supporters. At its core, social media is used with the intention of sharing our lives and what we love with each other, and we should fuel this expanded connection with as much art and beauty as possible. In 2018, I am grateful for the opportunities Francesca didn’t have, and hopeful for the female artists of the future.

Bella Chidlow, Changeroom 2018, ink on paper, 42 x 29.7 cm.

References:

Isabella Pedicini, Francesca Woodman (The Roman years between flesh and film), Contrasto, Italy 2012

Julia Wolkoff, ‘Reevaluating Francesca Woodman, Whose Early Death Haunts Her Groundbreaking Images’, Artsy.net, August 22, 2018

Olivia Fleming, ‘Why The World’s Most Talked-About New Art Dealer is Instagram’, Vogue.com, May 13, 2014

Carol Kino, ‘How Instagram Became the Art World’s Obsession’, Wall Street Journal Magazine, July 24, 2018

Wojtek Rozdzenski, ‘Selfie-feminism, the Sad Girl Theory and the Sad Girls of Instagram’, Daily Art Magazine, April 11, 2018