Eliza Burton reviews two exhibitions by women running concurrently at the Art Gallery of Ballarat, the first an ambitious survey of Australian modernism from the Gallery’s own collection and the second a group of contemporary artists engaged in discourse via podcast conversations with their colleague and artist Tai Snaith.

Becoming Modern: Australian Women Artists 1920-1950

18 May – 4 August 2019, Art Gallery of Ballarat. Find out more.

Tai Snaith: A World of One’s Own

15 June 2019 – 4 August 2019, Art Gallery of Ballarat. Find out more.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, 1929

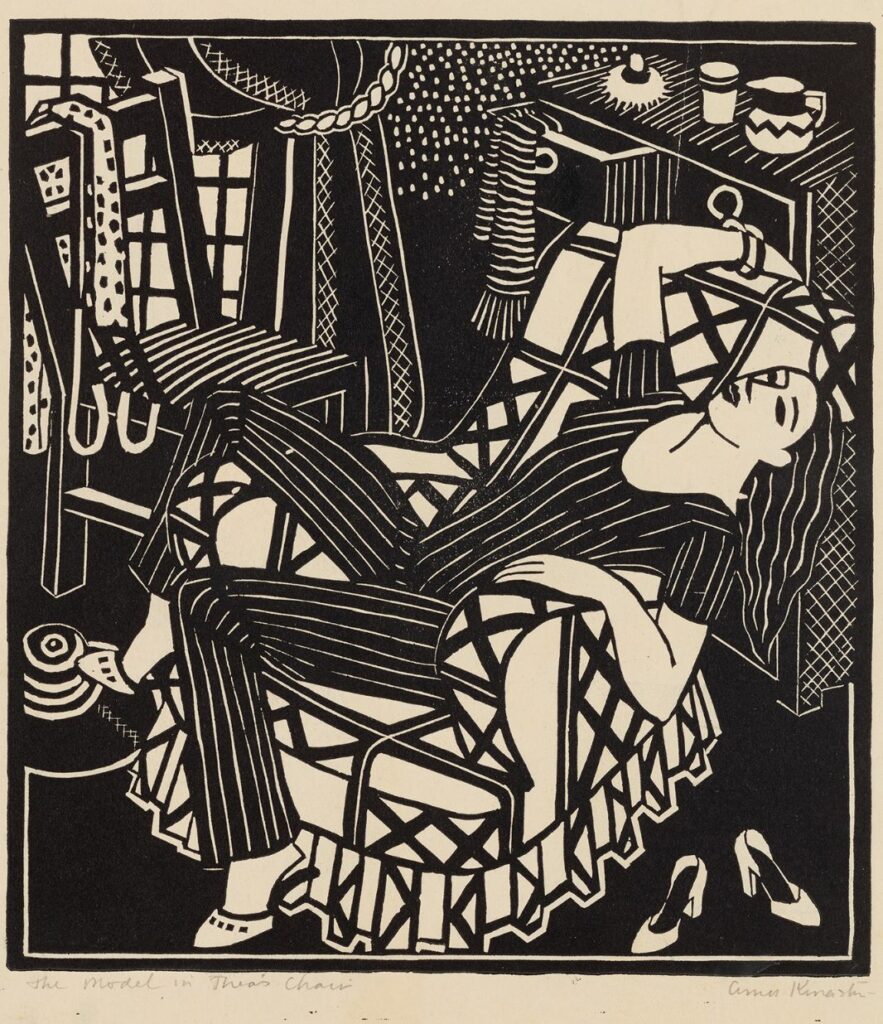

Amie Kingston, The model in Thea’s chair 1927-1928, linocut.

All-women exhibitions are often criticised for focussing too overtly on the gender of the artist and implying essentialist feminine themes, aesthetics and genres. However, such exhibitions can also demonstrate the way women’s art may be similar based upon external economic, social and political factors rather than innate femininity. To ignore the cultural factors at play in the creation of women’s art, particularly historically, is to ignore the difficulties women have faced making and exhibiting art.

Two current exhibitions at the Art Gallery of Ballarat provide a nuanced and exciting representation of women’s art, and offer convincing examples of the benefits of presenting women artists together. Becoming Modern: Australian Women Artists 1920-1950 takes works by women primarily from the gallery collection to provide insight into Australian women artists’ often forgotten innovative role in the first half of the 20th century. Tai Snaith: A World of One’s Own is based on Melbourne-based artist Tai Snaith’s ongoing podcast conversation series. This exhibition presents the work of six contemporary Australian women artists, offering a deep exploration of each artist’s creative process.

Whilst Becoming Modern looks at Australian women artists’ pivotal involvement in shaping the art world at the time, A World of One’s Own provides an insight into the contemporary art landscape. Running side by side, the two exhibitions parallel each other and create a more comprehensive view of Australian women artists and how far female representation has come. This is not to say there are no longer issues of gender discrimination in the art world, and these exhibitions are testament to the ongoing curatorial activism necessary to reinsert women artists into art historical narratives and support their contemporary practices.

Becoming Modern takes the period 1920-1950 to focus on how Australian women artists were able to innovate within the stylistic, financial and educational restrictions they faced. Throughout the period explored, open hostility to women from artists and critics alike was not uncommon. Work by women artists was often conflated with decoration and design, rather than high art and intellectualism. Influential critic and director of the National Gallery of Victoria J.S. McDonald was quoted as saying there had never been a good female artist.[1] Of successful artist Thea Proctor he wrote, “Miss Proctor is one of those rarities – a woman who can draw.”[2] Despite these restrictions, women artists were at the forefront of developing a modernist sensibility in Australian art, although this contribution was largely unrecognised at the time.

The exhibition covers five rooms that progress vaguely chronologically and explore the growing societal freedom for women in the early 20th century, the rising role of travel and overseas influences, feminine aesthetics, Australian scenes and women’s role in Australian modernism. Upon entering the first room of the exhibition one work is given its own wall space, and in many ways acts as the key opening artwork. Strangely this painting, The conversation, is by male artist George Bell. Although the caption draws attention to Bell’s depiction of Thea Proctor, it is still an odd way to begin an exhibition of women artists. It implicitly suggests that the other art by women artists that fills most of the exhibition is not up to the same standard, which the calibre of works that follow proves to be untrue. Whilst this work may help to contextualise some of the women artists on display, male artists’ representation of women is not a subject that needs more space, particularly in the context of an exhibition that highlights the artistic voice of women.

However, the remainder of the exhibition provides a greater exploration of how women depicted themselves. Works like Ethel Spowers’ Resting models and other nude paintings, prints and preliminary sketches show women representing their own bodies, and are a welcome departure from the typical male-painted female bodies often seen in art galleries.

Ethel Spowers, Resting models 1934, colour linocut.

A highlight of the exhibition is the variety of media, including advertisements, ceramics, prints, paintings, magazine covers, sculptures and cartoons. Unsurprisingly prints make up a large portion of the work on display. An abundance of prints by women is common in public collections, both due to the high volumes of most printed material and the ease with which prints can be acquired and stored, making it simpler for institutions to diversify their collections.[3] Works by artists such as Helen Ogilvie, Norbertine Bresslen-Roth and Amie Kingston, among many others, exemplify women artists’ depth of experimentation and mastery within printmaking. The small scale of many of the works is also unsurprising given many women artists were focussed on commercial sales, with works of domestic scale selling more easily than large-scale paintings.

To be commercially successful it was also to women artists’ advantage to conform to expectations about feminine art. Accordingly, most works in the exhibition are still lifes and domestic scenes, or depictions of flowers, animals and nature. It is within these genres however that artists chose to experiment and to bring a more modernist aesthetic. Works by Margaret Preston are a key example of the success some women artists found innovating within these restricted subjects.

Although women artists were largely encouraged to work within these traditionally feminine genres, there are some striking examples of works that eschew these expectations. Jessie Traill’s etchings in particular stand out in a room filled with prints of nature, animals and scenes of travels abroad for their dark depiction of industrial and metropolitan settings. Another novel example is Bertha Bennet Burleigh and Betty Newman’s cartoons from The Bulletin, a publication that rarely published satirical cartoons by women. These examples, although not numerous, are an exciting insight into the more unexpected areas in which women were working.

A key strength of the exhibition is the focus on Ballarat. 97% of the works are from the gallery’s collection, and no doubt this exhibition provided an opportunity to revisit many artworks that have rarely been publicly displayed. There are a large number of works by artists with links to Ballarat, including Alice Watson, Nornie Gude and Hilda Rix Nicholas. This connection helps to tie an exhibition that widely examines the role of Australian women artists to a local context. Many works are also not by recognisable names, which allows for the rediscovery and reconsideration of lesser-known artists. Visitors are provided an opportunity to learn about artists such as Mary Alice Evatt and Nan Hortin and the influence these kinds of figures had in the art world at the time.

Mary Alice Evatt, Portrait of Moya Dyring 1938, oil on canvas.

Becoming Modern closes with some of the more highly recognisable artists in the entire exhibition, such as Grace Crowley, Joy Hester, and Mirka Mora, whose works have a particularly bold and modernist aesthetic. Here we see artists moving further into abstraction. Displaying these works at the end represents not only a chronological progression but also demonstrates the important experimentation and influence of preceding women artists who are less well known, and the legacy upon which these well-known artists are built.

Grace Crowley, Abstract painting 1950, oil on cardboard.

This legacy is extended into Tai Snaith: A World of One’s Own, which represents contemporary Australian women artists. Moving into the second exhibition provides a shift in atmosphere and scale. The walls change from white to black, and the artworks go from small and numerous to large and sparse. The often more crowded, sometimes Salon hang of Becoming Modern against clean white walls reflects the context in which those works were created, and their domestic scale. The black rooms of A World of One’s Own on the other hand give the exhibition a more contemporary feel, with large works given space on the walls to encourage prolonged engagement with each artwork.

A World of One’s Own is based on the second series of Tai Snaith’s podcasts of the same name, in which Snaith speaks to female and non-binary artists about their artistic practices. The project started in 2017 as part of the ACCA exhibition Unfinished Business: Perspectives on art and feminism, and the second season has been funded by the Australia Council for the Arts. The first two rooms of the exhibition are filled with the works of artists whom Snaith has spoken to in the second series of her podcast. Each of the five artists, Sanné Mestrom, Megan Cope, Stanislava Pinchuk, Luccrecia Quintanilla and Esther Stewart, present two or three works in a variety of mediums.

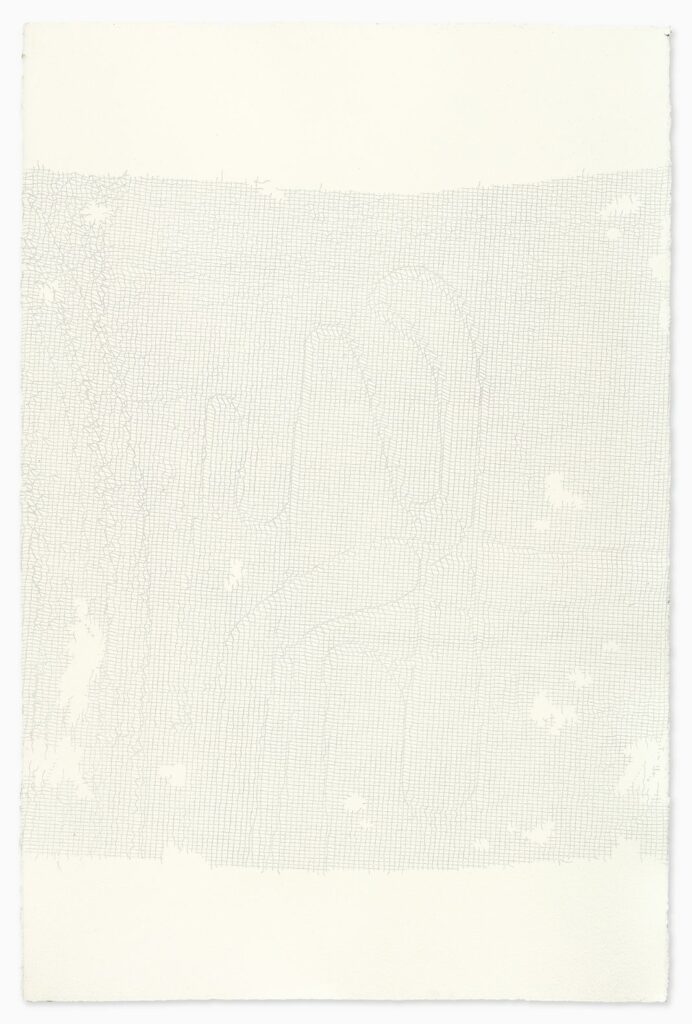

Stanislava Pinchuk, Calais ‘Jungle’: Topographic Date Map: (Entire Camp Evacuation I) 2018, pinholes on paper. Courtesy of Stanislava Pinchuk, photograph Matthew R Stanton

A highlight of this exhibition is Stanislava Pinchuk’s work based upon her time spent in the Calais ‘Jungle’ refugee camp. At first the large-scale Calais ‘Jungle’ works look like blank white paper, but closer inspection reveals thousands of tiny pinpricks in the surface creating delicate patterns that reflect the data she collected whilst visiting the refugee camp. Her data collecting involved mapping the changing topographies of the site caused by the people that moved through it. Accompanying the paper works are four terrazzo blocks created using objects and debris Pinchuk found left in the ground during evacuation of the site. The immediate appeal and minimalist aesthetic of these works is quickly undermined by the dark subject matter, and the pain, trauma and loss contained in the disassociated materials. The tiny pinpricks of the paper works also allude to women’s work and the laborious, repetitive motions associated with traditional feminine activities such as lace-making and embroidery, processes which additionally involve physical pain.

Similarly alluding to these traditionally feminine processes is the work of Esther Stewart. Presented in the same room as Pinchuk’s black and white pieces, Stewart offers a brightly coloured contrast. Her two wall hangings jut slightly from the wall and the tops are tightly stretched to resemble taut bed sheets. In her conversation with Snaith, Stewart discussed the shifting connotations of the bedspread and the growing aesthetic of messy, laid-back beds that may also suggest a changing acceptance and openness of what happens in the bedroom. Despite the aestheticised presentation of the bed sheet here, colourful and hung up on the wall, the bed as an intimate and personal site draws to mind Tracey Emin’s My bed and the symbolic sexual liberation for women that can be associated with this object.

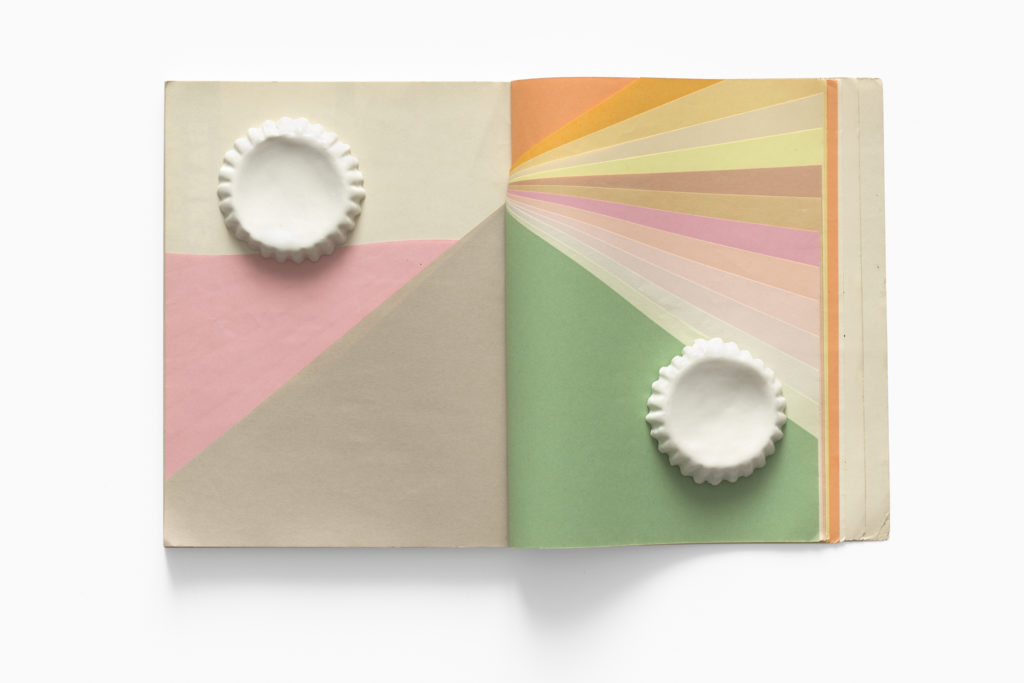

The final room has a far more relaxed feel than the sparse formal hangs of the first two rooms. Here Snaith presents her own responses to the artworks and artists we have just seen. Accompanying these works are journals and sketches documenting Snaith’s creative processes and conversations, and an invitation to sit and listen to the podcast in the form of a chair with an iPad. Like the preliminary sketches hung in Becoming Modern, the inclusion of sketches, journals and relevant reading materials means that we are again treated to an insight into the process of creation. This is a successful way to bring the informal nature of the podcast conversations into the exhibition space, and to reiterate the focus on artistic processes that is the primary topic of these conversations.

It is also interesting to see Snaith explore the motifs, materials and themes of each artist in her response pieces. Seeing the artistic responses highlights ideas of community and learning from each other that have historically been important to women artists. However, the wall labels don’t inform visitors which artist Snaith’s works correspond to. Although some are obviously linked through their repetition of certain objects and shapes, in many the reference is ambiguous. This isn’t helped by the fact that there are no accompanying didactics for the individual works discussing their meaning. Exhibiting the corresponding works in the same space as the original artwork may have allowed for a greater visual conversation between the two works.

Tai Snaith, Open Book for A World of One’s Own 2018, porcelain on paper. Courtesy Tai Snaith, photograph Matthew R Stanton.

That being said, the intimate and less intimidating feel of the final room perhaps makes up for lack of clarity. The chair offers a space to sit down and spend time with the exhibition and the artists, and the podcasts provide a more informal voice than traditional educational audio guides one is used to finding in museums. Here the focus is not only the process of creation, but also the process of conception and the forming of artistic ideas, and the importance of community and conversation for these processes.

This is elegantly summed up by the title of the podcast and exhibition, A World of One’s Own. The shift of the original quote from a “room” to a “world” entails both an expansion of opportunities and alludes to the interior “worlds” of the artist that are discussed. Virginia Woolf’s quote is also highly relevant to Becoming Modern. What becomes clear throughout the course of this exhibition is not only the innovative nature of many modernist women artists, but also their reliance on opportunity and money to achieve success. Woolf alludes to the need for women to have a certain freedom from domestic constraints as well as financial constraints. And tellingly, access to education, finances, and a space of their own to create art was key to the success of women artists at the time, a privilege not afforded to many. Unsurprisingly, although A World of One’s Own features only six artists, there is a greater plurality of voices and cultural backgrounds. This is a welcome change and reflects the increasing intersectional and inclusive nature of contemporary feminist and artistic communities.

Tai Snaith, Dancing Through Different Doors 2018, glazed porcelain. Courtesy Tai Snaith, photograph Matthew R Stanton.

A strong takeaway from both exhibitions is the importance of communities. Firstly, admittance to certain communities that allow and encourage the creation of art, and secondly the formation of communities to support and share artistic ideas and success. Both exhibitions are benefitted by their proximity to the other; Becoming Modern provides an important context for A World of One’s Own, and likewise the latter exhibition provides an extension of the ideas, themes and legacy of the historical works. Whilst A World of One’s Own demonstrates how far women artists in Australia have come in terms of their subject matter and depth of thematic concerns, the same innovative and experimental urge is consistent throughout both exhibitions. One can only hope that artworks such as those exhibited that demonstrate the dynamism and plurality of women’s art continue to be widely exhibited and seen.