History Afresh, Zahalka Style

ZAHALKAWORLD – an artist’s archive

Museum of Australian Photography, Melbourne, 10 June – 10 September 2023

By Andonis Piperoglou.

Anne ZAHALKA, The breakaway, 1985, from the series The Landscape Re-presented, chromogenic print, brown paper; plywood; balsa wood, 100.0 x 122.0 cm. Courtesy of the artist represented by ARC ONE Gallery (Melbourne) and Dominik Mersch Gallery (Sydney).

For over forty years Anne Zahalka has aided us to reconsider how we frame Australian pasts. A playful photo-media artist, she has managed to reorientate historical myths that frequently centre Anglo men as pioneering founders. With a nuanced feminist lens that is closely informed by a layered diasporic sensibility, Zahalka subtly conveys how the stories we tell about Australia can be more inclusive.

In ZAHALKAWORLD – an artist’s archive at the Museum of Australian Photography, we are invited into the many modes of her artistic practice. Centred around her home archive, the exhibition brings together key bodies of her work, alongside personal objects that inform and inspire her. Intimate and encompassing, the exhibition is a tour de force of photographic curation.

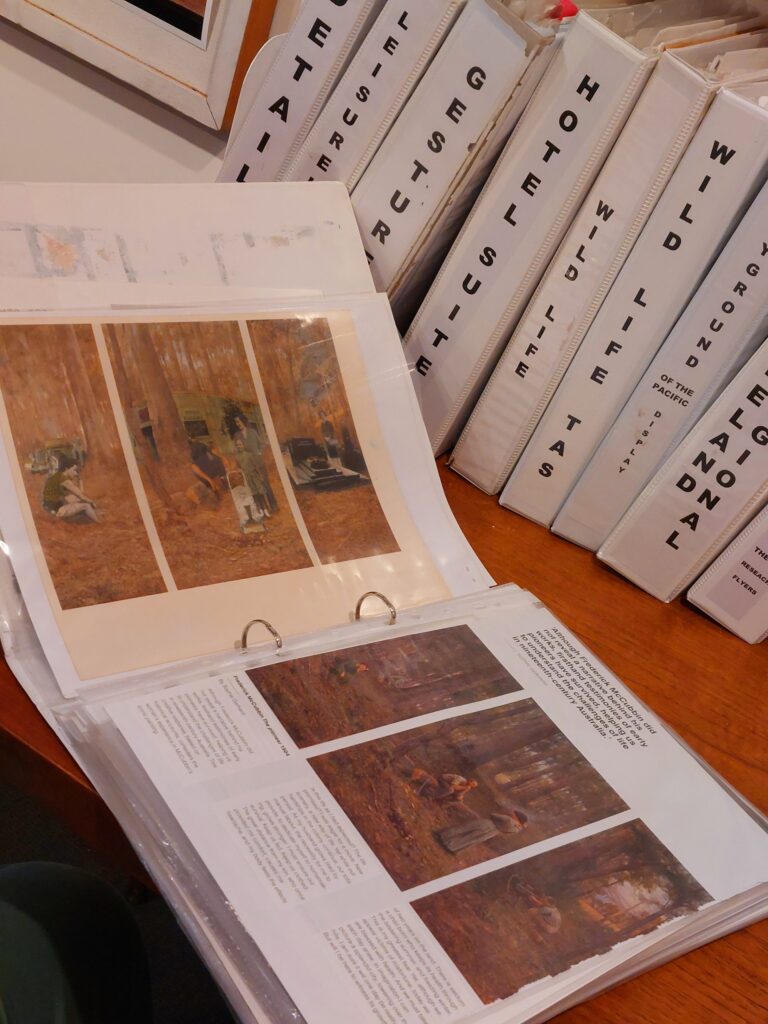

Retrospectively leading you through her creative practice, while giving off a feeling that a reconfiguration of Australian history is unfolding, the world of Zahalka that we are invited to journey through reveals a spirited career of questioning. At the centre is a recreation of her home studio. Walls depict her bookshelves, notations and a window to the outside world, while a small desk is lined with archival folders. The reconstructed studio is tantalising to anyone with historical sensibilities. As a migration historian who teaches and researches at the University of Melbourne, I am familiar with how official archives can be alienating and unwelcoming. I have become accustomed to windowless rooms, dusty boxes and the strict rules enforced by archivists that often oversee the material records of men of authority. Yet in Zahalka’s archive, the inquisitive researcher is invited to touch, feel and think freely among records that favour Australian plurality.

The folders at the small desk are boldly labelled. They are full of bulked-up plastic sleeves. Full of curatorial designs, promotional material and exhibition reviews, these folders act as an honest entry into the emergence and endurance of a distinctive artistic approach that has centred memory, people and landscapes. Folders titled “Displace Persons” and “Leisureland Regional” suggest an evolving style that grapples with the reception and critique of historical myths. Bygone typewriter scripts, newspaper cut-outs, exhibition CDs and glossy pamphlets reflect Zahalka as an artist in motion. Deep diving into her own past, we learn through these well-kept records that Zahalka has been tweaking, rearranging and testing the threads that bind us to collective memory. A child of refugee parents – with a Jewish Austrian mother and Catholic Czech father – we learn that the absence of migration in the Australian legend has been a constant in her practice. Ideas around leaving, refuge, travelling and settling are never far from the surface, as are topics that are tied to the fought politics of dispossession, genocide and survival.

Landscape Re-presented folder open to workprint of Zahalka’s The Immigrants 1983 and a reproduction of McCubbin’s The Pioneer torn from a page of the NGV magazine. Photo by the author.

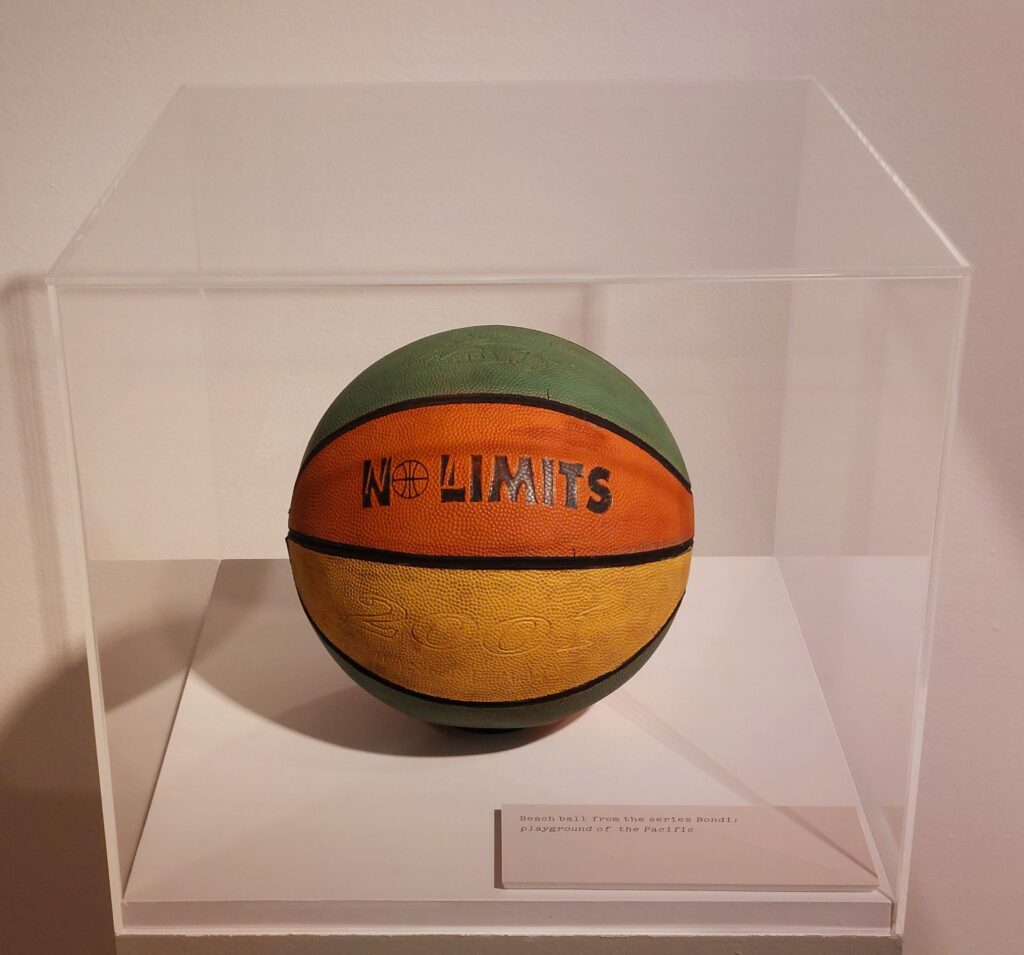

In 1989, Zahalka reworked Charles Meere’s Australian beach pattern 1940 – an embodied representation of an assertive beachy whiteness – into The Bathers 1989. The Bathers, adorning the covers of a range of popular books and magazines and perhaps her most well-known work, tells a story of a changed Australia. A hairy chest and dark hairdos symbolise the realities of beach-life. Her recreation acts as a gentle but powerful reminder that in the lead up to the 1988 Australian bicentenary everyday multiculturalism was not fully represented in the country’s historical mindset. During the aftermath of 9/11 and the Cronulla riots the country once again underwent further demographic change. Confronting stereotyping head-on, Zahalka reworked her iconic image for a new generation. The New Bathers 2013 masterfully represents – and by extension documents – another beach-life. Awkward stares and the pulling of an irksome Australian-flag beach towel bring attention to cultural tensions, but also new faces, bodies and styles direct our gaze towards seeing the beauty of cultural interaction. Near where The New Bathers hangs is a cabinet that houses the object that Zahalka uses to represent Meere’s beach ball. It is a colourful basketball printed with the words “NO LIMITS” – a nod, perhaps, to the limitlessness of transcultural possibilities.

Beach ball from The New Bathers 2013. Photo by the author.

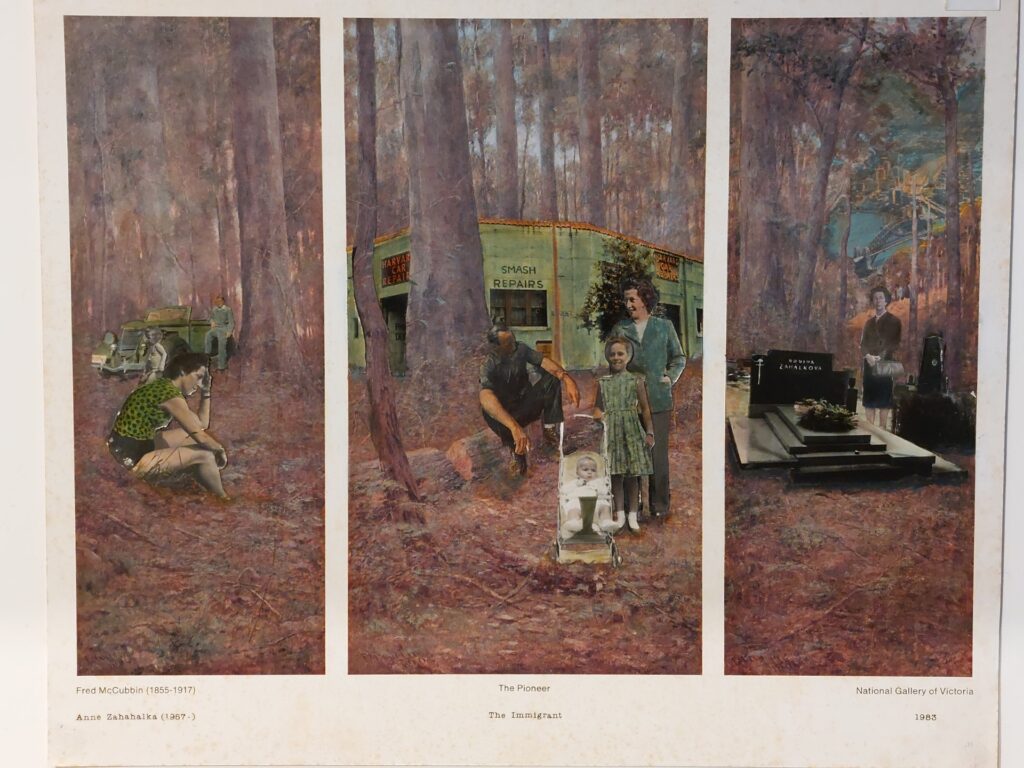

Beyond Zahalka’s familiar images, we are also introduced to less well-remembered works. Her reworking of Frederick McCubbin’s monumental triptych The Pioneer 1904 becomes The Immigrants 1983. McCubbin’s work was produced three years after Australian federation and illustrates the story of a settler family making a living in the Australian bush. The painting’s depiction of a couple selecting land in the bush, making a family home and, after time has passed, the growth of an urban centre, has been routinely read as a representation of colonial progress. Openly questioning this celebrated historical trope Zahalka, we discover, works hard to subvert this prevailing pioneering ethos. Removing McCubbin’s 19th century settlers, she inserts her own family members making life in the bush setting. Short shorts and a polka dot blouse replace a heavy long green dress, her father’s smash repair shop erases the settler cottage and the bustling metropolis of Sydney is visible through the eucalypts. This reworking of a much-valued piece of Australian impressionism situates the Zahalka family as new pioneers. In so doing, Australia’s celebrated post-war migrant story is re-imagined. The so-called new Australians are at home in the landscape.

Original collage by the artist with hand-coloured family photographs on reproduction of The Pioneer 1904 by Frederick McCubbin.

Towards the end of the exhibition a series of recordings of Zahalka are screened on rotation. Intimate and honest, the recordings act as a genuine means to connect with the audience. We see the making of The New Bathers – as a composition and as a process. Via mini documentaries – some from earlier exhibitions – we hear Zahalka’s inviting voice. Footage of her walking around her home studio give detail to how she envisioned and planned ZAHALKAWORLD. Watching her in her home-space, Zahalka’s warm tone and embracing smile caps off our journeying of a career dedicated to exposing the mythologising of history.

Still image of The making of The New Bathers in the projection booth with Zahalka directing (far right). Photo by the author.

Zahalka remakes Australian history. By superimposing over key symbols that have come to embody Australian mythmaking, she has delicately prodded and picked apart exhausted yet lingering national narratives. Restoring via clever composition, she challenges the stories we tell ourselves about the past by inserting palatable meaning. In doing so, Australian history is propelled into new visual form. Via Zahalka’s revisionist gaze, the men of our pasts no longer dominate the national story. Redirecting our gaze, Zahalka permits us to rethink our history. By walking through Zahalka’s world an interpretation of our past unfolds – an interpretation that is simultaneously comforting and necessary.

Dr Andonis Piperoglou is Hellenic Senior Lecturer in Global Diasporas at the University of Melbourne.