By Juliette Peers

Art historian Juliette Peers reviews two books on women artists, the recently published Odd Roads to be Walking: 156 Women who Shaped Australian Art and Through Line and Colour: Forty Irish Artists of the 20th Century, published in 2010.

Lead author on both books was Paul Finucane, an Irish doctor now resident in New South Wales. Taken together they provide the opportunity to compare the careers and achievements of women artists in two very different countries, and the obstacles they faced working as professional artists. As a doctor Paul Finucane is fascinated by the artists’ life stories as much as their work. He also considers the social experiences that shaped these women’s lives. If 20th century Irish women artists were witnesses to major social and political change with the formation of the Irish Free State and the Republic of Ireland, then are we also witnesses to newly changing times for artists trying to keep their lives and their practices afloat? Juliette Peers suggests that Paul Finucane’s writing have an unexpected resonance with current rapid seismic shifts in cultural and social life. Closures of businesses and restrictions on movement in the wake of the pandemic has put Australian creative workers under extreme economic pressure, as levels of recession and unemployment break previously established records. Simultaneously creating the “perfect storm” to submerge artists, a fresh set of tertiary education reforms threatens changes to the teaching and learning landscapes around humanities and art. Beyond Australia expected templates for making and evaluating art are increasingly being challenged by calls for social change. Where does the act of documenting the careers of overlooked artists now stand when researching the past may be seen as irrelevant to more urgent, present-day challenges? This essay sifts through some of these pressing issues.

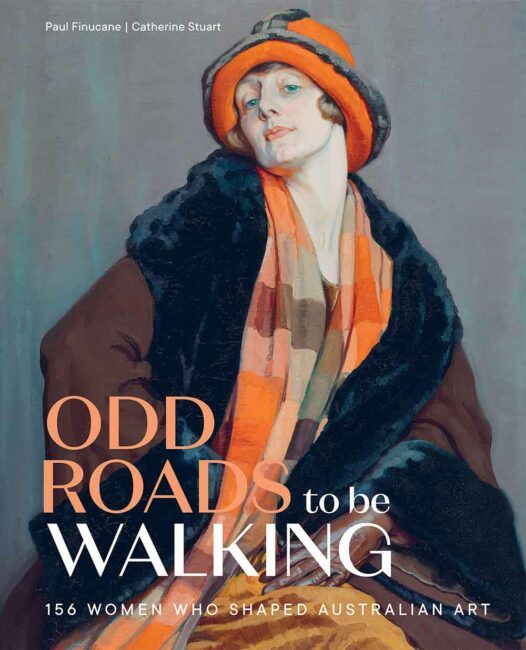

Odd Roads to be Walking: 156 Women Who Shaped Australian Art by Paul Finucane and Catherine Stuart, 2019

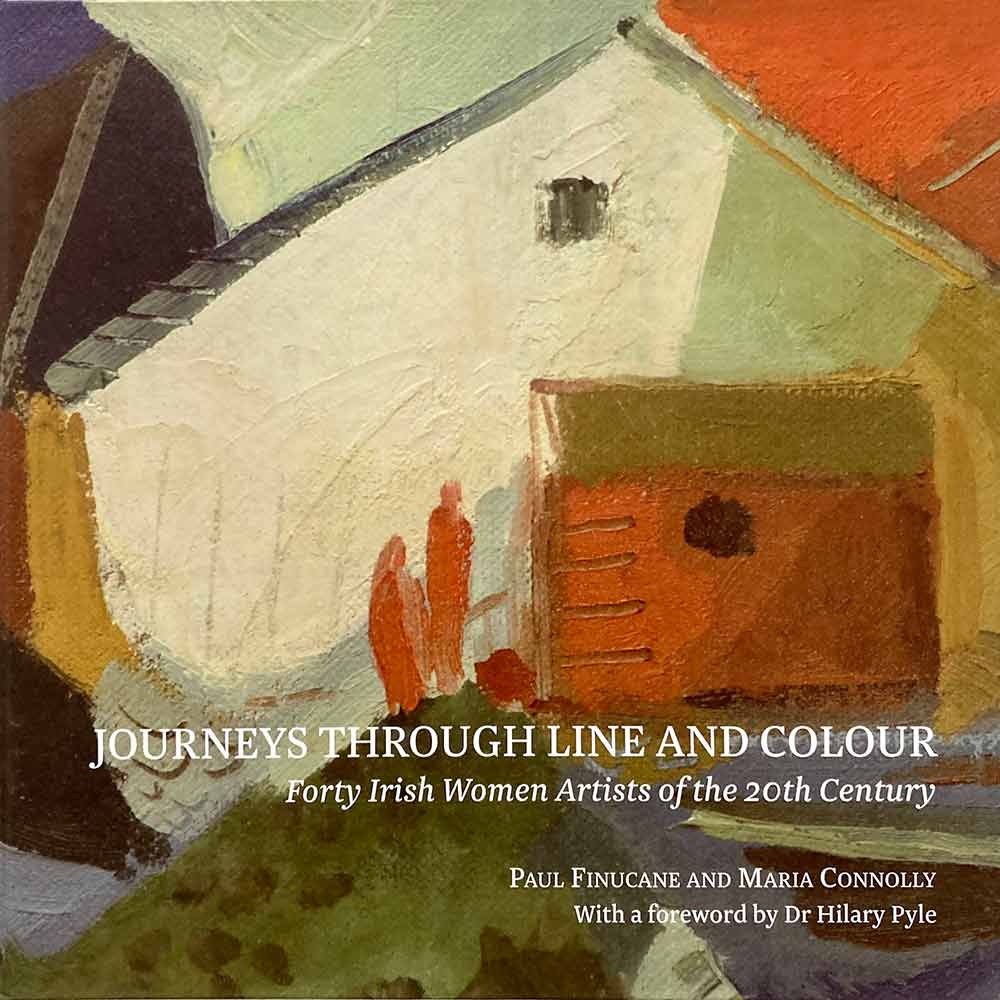

Journeys Through Line and Colour: Forty Irish Women Artists of the 20th Century, by Paul Finucane and Maria Connolly, University of Limerick Press, 2010

These two books present a rich cornucopia of women’s artworks in full colour, backed up by overviews of the careers of close to 200 women artists, considering that the texts also capture associate contemporaries and peers. The quantity of artists captured in Odd Roads allows for some unfamiliar data mining. Entries span Ellis Rowan’s rise to fame in the 1880s to Lina Bryans’ death in 2000, even including some late 20th century contemporary artists such as Barbara Hanrahan and Kerry Giles Kurwingie, who died relatively young. Who would have realised before that Margaret Coen, Lina Bryans, Elaine Haxton and Emily Kame Kngwarreye were close to contemporaries? Or that Rosalie Gascoigne, who achieved considerable fame as a contemporary sculptor in the 1980s and 1990s, was three years older than relatively short-lived Joy Hester, whose art is associated with the Heide Circle of the 1930s to 1950s and who died well before the older woman began exhibiting? The biographies assimilate women from outlying states such as Western Australia and Tasmania into a chronological run with far better known names from Melbourne and Sydney. The diverse options for surviving as a professional woman artist in 20th century Australia emerges from the pages of Odd Roads. This is an unfamiliar trajectory. Conventional academic and curatorial practice tends to detach children’s book illustrators, for example, from easel painters. Florence Broadhurst is usually examined in terms of design history or the sensational story of her life and death. Here Peg Maltby and Florence Broadhurst are discussed alongside Margaret Preston and Clarice Beckett. Like-wise integration of Indigenous artists by date of birth rather than treating them as a distinctive and separate vision, does not follow industry expectation, but the impact of their work is not diminished. The spread of portraits of the artists featured in Odd Roads is an eloquent piece of data visualisation indicating the size of the contingent of significant 20th century Australian women artists and making them real for the reader.

Cover, Journeys Through Line and Colour: Forty Irish Women Artists of the 20th Century, by Paul Finucane and Maria Connolly, University of Limerick Press, 2010.

Paul Finucane, the major author of both texts, admits to being fascinated by life-stories and launching these vast biographical projects for that reason:

As a medical doctor (a Geriatrician) who spends a lot of time with older people, many of whom have lived extraordinary lives and all of whom have lived through extraordinary times, I’m often fascinated by their life stories. In my professional life, I strongly identify with the notion that ‘the person with the illness is more important than the illness in the person’. To apply this to my interest in art (as an ‘enthusiastic amateur’), I tend to be as curious about the person who created the art as about the artwork per se. Conversely, for me to know something about the life of the artist tends to add a whole new dimension to her/his work.

While the work of many Australian artists certainly moves me, I find that their life-stories move me at least as much. How could anybody learn something about the lives of the like of Joy Hester, Florence Broadhurst, Hilda Rix Nicholas, Stella Bowen, Clarice Beckett, Kate O’Connor, etc. etc. etc. etc. and not be moved? When I now look at something by Joy Hester, I think I have at least some awareness of the emotional turmoil in her personal life and how this underpinned her art. [i]

Most of the featured artists enjoyed careers that substantially played out in public. Their works were collected by major institutions and their lives were well documented both during their lifetime and retrospectively by curatorial and academic writings. Yet in Ireland, as in Australia, a degree of cultural amnesia has grown up around these artists and thus their stories have not always been accessible, particularly to the general reader. Whilst for the major artists there are two to three pages of biography and large colour plates, many artists’ lives and works could sustain a study in their own right, beyond this introductory compendium. The oeuvre of images and narratives defies easy summary due to the amount of material that has been assembled from so many sources. Thumbing through the books themselves is the best proof of their range and value.

Taking both titles as a whole oeuvre, four generations of women artists are sampled here, bringing their works and life-stories together in an attractive, accessible format. A general audience will greatly enjoy both books, although the relative lack of referencing of sources limits the usefulness of the Australian volume for students and professionals. Whilst there are pages of endnotes, most of these are sidebar-style explanations of events and people, providing context to a non-Australian readership, rather than crediting information sources. This absence of expected and customary acknowledging of previous contributions remains both a concrete and an ethical shortfall that undermines Odd Roads‘ stated championing of Australian creativity and women artists. Ultimately this text interacts with and draws from four, nearly five, earlier decades of academic, curatorial, local history and even family history work that has sought to consolidate against indifference, (if not hostility) biographical and critical materials around Australian women artists. To assemble a publication of the impressive scale and breadth of Odd Roads in the space of three years would have been impossible without this previous body of work. Even a page of further reading could have at least directed the general reader to compilations such as the early bibliographies of previous art scholarship by Caroline Ambrus and Elizabeth Hanks [ii], or the multi-authored Heritage, edited by Joan Kerr with Anita Callaway [iii] and offered appropriate acknowledgement. The Heritage project itself calibrates the care and devotion of a large nation-wide phalanx of researchers a quarter of a century ago; their words and energy are the foundation upon which Odd Roads is built. Without the predecessors of 25 years ago, the current project would have been impossible.

This forgetting is not solely the premise or fault of Odd Roads, as large institutions in Australia tend to be parsimonious in acknowledging outsider contributions to the central narratives of public culture. The rapid fading of the reputation and achievements of major artists and researchers of the recent past, who worked hard particularly to establish women’s art in the public eye, relates to a much broader phenomenon of “presentism”, where modern politics and values dominate any current modelling of cultural debate. A lack of questioning of a tunnel vision framed by modern politics, or even recognising the limitations and distortions of these paradigms is rapidly becoming a go-to in multiple cultural conversation and sense making practices.

In Australia, at least, some important feminist and activist artworks – including influential work by Indigenous artists and curators – from the 1970s-1990s are substantially unfamiliar to younger artists and curators and thus have little traction in academic or curatorial models that shape current intense and rapidly changing debates. Now across the globe history has moved rapidly from being dull or irrelevant to being regarded as unreliable, biased and deeply malign, and thus not deserving any special status or “airtime”. Equally, given the widespread confidence expressed in current and new narratives, very few cultural workers feel the need to push further into unfamiliar narratives and practices, which are often assumed to be lesser or irrelevant and thus not meriting further attention, when aesthetics are increasingly trounced by practicality.

Whereas Odd Roads floats above these uncomfortable times for empirical histories, Journeys Through Line and Colour explicitly cites the very specific social and political reasons that have pushed many early 20th century Irish women artists from the agora. Indeed Journeys casts itself as a tool to address this forgetting, with information on location of works, further reading and even advice about the artists’ profile in auctions, the antique trade and resales, to encourage collecting of these forgotten artists. This level of practical advocacy does not translate to Odd Roads, but the detail and liveness of the reconsideration of Irish women artists is welcome and serves as a model of popular feminist redress. If Odd Roads presents traditional, ineffable connoisseurship with its mission to locate and celebrate creative excellence, current and present constructs of the parameters of cultural broking are moving rapidly towards a very trajectoried and functional canon and away from the post-enlightenment focus on the artists’ choices and skills as central to art appreciation. This new functionality demanded from the visual arts contrasts to the all-in townhall meeting approach of Odd Roads. If cultural debate now demands acknowledgement, inclusion and respect of the disempowered, then Odd Roads could be equally seen as arrhythmic to new practice, wrongly or perhaps even rightly.

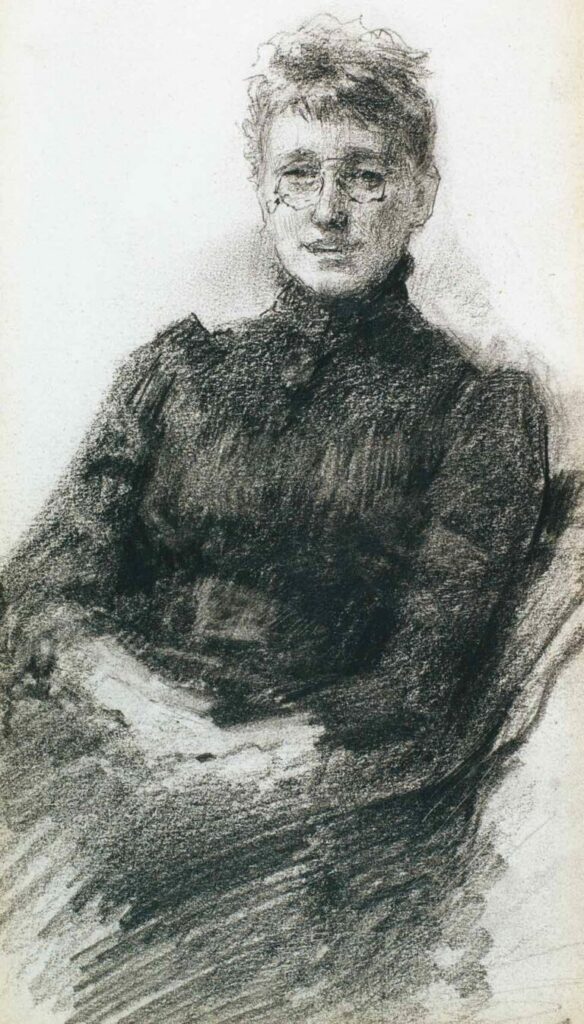

Sarah Purser, Self portrait (detail) 1939, pencil and chalk on paper, 20.5 x 10.5 cm, National Self Portrait Collection, University of Limerick.

Whilst many readers may find the Australian artists familiar, their Irish contemporaries are relatively little known in Australia, although Sarah Purser’s accomplished late 19th century portraits appear in general histories of European and American women artists, due to her skill. Equally impressive are her confident and ambitious career building and organisational skills. Her entrepreneurial drive stands out amongst late Victorian women artists in her generation. If critics quibble – albeit unnecessarily – about the value of late 19th century Australian women artists to mainstream Australian cultural memory [iv], Sarah Purser worked energetically to expand cultural resources in Ireland when it was under British rule and later in the new independent Republic. A substantial influence was exerted over her Irish contemporaries through her lobbying to establish a gallery of modern art in Dublin, her foundation membership of the Dublin Art Club in 1886 and the organisation of a stained glass studio An Tur Gloinne in 1903, that was responsible for many public and ecclesiastical commissions across Ireland. Major contemporary women artists Wilhelmine Geddes, Lady Beatrice Glenavy and Evie Home were employed in this important hub of Irish craft and design.

Sarah Purser, Miss Maud Gonne 1898, pastel on paper, 43 x 27 cm, Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane.

Sarah Purser’s career does not only register in Irish art history, but is unique globally amongst her generation. Turn of the century women artists in France and Britain never were permitted the degree of official and corporate agency that Sarah brokered for herself. In central Europe portraitist Margaret Parlarghy did enjoy that same high profile, and it seems plausible that both Sarah Purser and Australian Violet Teague may well have pursued grandiose and complex modes of portraiture due to Parlaghy’s widely publicised example, but no concrete trail of primary sources can be established. Ironically Käthe Kollwitz, who now enjoys a towering political and cultural reputation beyond most of her male and female contemporaries from late 19th century Germany, was an outsider when compared to Parlarghy in the 1890s. Australian Ethel Carrick Fox certainly displayed something of this entrepreneurial breadth and energy, although in the smaller rarefied scale of the avant garde, and for a concentrated shorter period of time in the last few years of the belle epoque.

Not all the artists in both texts are “lost”; some such as Joy Hester, Margaret Preston, Clarice Beckett, Constance Gore-Booth, Edith Somerville, Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, May Gibbs, Peg Maltby, Florence Broadhurst, Mary Alice Evatt and perhaps even Emily Kame Kngwarreye have attracted substantial cross generational academic and popular attention to their life and work across many media and fora, including film and audio documentaries, even novels, theatre pieces and a ballet. Although technically the fame of Constance Gore-Booth, later Countess Markievicz, and Edith Somerville is not an art historical matter, both women are better known for achievements outside of visual art. As well as painting, Somerville was one half of the Victorian and Edwardian literary duo Somerville and Ross, widely read and remembered for the humorous novel Some Experiences of an Irish RM (and its sequels). A very successful BBC/RTE television series in the 1980s placed her in the public eye again.[v] Academics in English Literature, Irish Literature, Victorian Studies and Queer Studies disciplines have increasingly researched Edith Somerville over the past thirty to forty years.

Constance Gore-Booth’s political career has far outpaced her original intention to be an artist in public memory. She is famed today as a key figure in the 1916 Easter Rebellion in Dublin, who escaped execution only due to the negative press that a state sanctioned killing of a woman would attract. Later she became the first woman appointed to a cabinet position in a Western democracy (by the Irish government) [vi]. Journeys emphasises her considerable youthful investment in becoming an artist, which included leaving Ireland to seek more advanced and comprehensive training. Four generations of women from Australia did exactly the same as the young Countess Markievicz in leaving home and attending art school in Europe.

Curiously the most famous historic Irish woman artist for a non-Irish audience – art deco architect, designer, liberated woman and queer icon Eileen Grey – does not appear in Journeys, although Florence Broadhurst does feature in Odd Roads. Other important Australian women in design are not included. Marion Hall Best, for example, is of sufficient distinction and influence and equally Frances Burke, known professionally and personally to a number of the Odd Roads artists who bought or commissioned work. On the other hand there is a major naïve/outsider artist Gretta Bowen in Journeys but not Lorna Chick in Odd Roads, although Lorna’s reputation and visibility has declined over the past few decades.

Dorrit Black, The Bridge, 1930, oil on canvas on board, 60 x 81 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Reading Journeys and Odd Roads offers a fresh expanded perspective on the familiar story of the interwar generation of women artists. Modernist and academic women artists in Australia and Ireland shared the same professional experiences. They enrolled in the same Parisian ateliers across four decades or more, from the conservative Academie Julien, Delecluse and Colarossi to the later modernist classes taught by Andre Lhote and Albert Gleizes, as well as the free Academie de la Grand Chaumiere. Curiously the talented cluster of Australian-based linocut printmakers who studied at Claude Flight’s Grosvenor School in London including Ethel Spowers, Eveline Syme, Dorrit Black and Eileen Mayo do not appear to have an equivalent amongst Irish artists, although this may be due to selection criteria for the Journeys anthology. After finishing their training, Australians and Irish often shared the ambition to be seen in the same prestigious international fora, Royal Academies and Salons, the Society of Lady Artists, as well as groups with more local impact.

Women artists in Ireland enjoyed one advantage over their Australian contemporaries: they lived closer to key artistic hubs, Paris for training and the avant-garde and London as a major focus for exhibiting, commissions and patronage. From Ireland there was relatively easy access to the whole of Europe, including the Mediterranean, for subject matter. Even without the driver of artistic pursuits, many of the Irish artists were from wealthy families, cosmopolitan, well connected and well-travelled. The Australians were mostly not so socially and economically well-placed as the women from the “big house” Anglo-Irish families.[vii]. All Australian art students were geographically at a disadvantage in the days when ships provided the only (and lengthy) means of intercontinental travel. In terms of looking at national histories and art histories, the wealth that enabled many of the Irish women’s independent careers was derived from the labour of the tenants on their family estates, and their freedom of movement and social status from their families’ upper-class privilege when Ireland was ruled from London.

Mainie Jellett, Achill horses 1944, oil on canvas, 61 x 91 cm, National Gallery of Ireland.

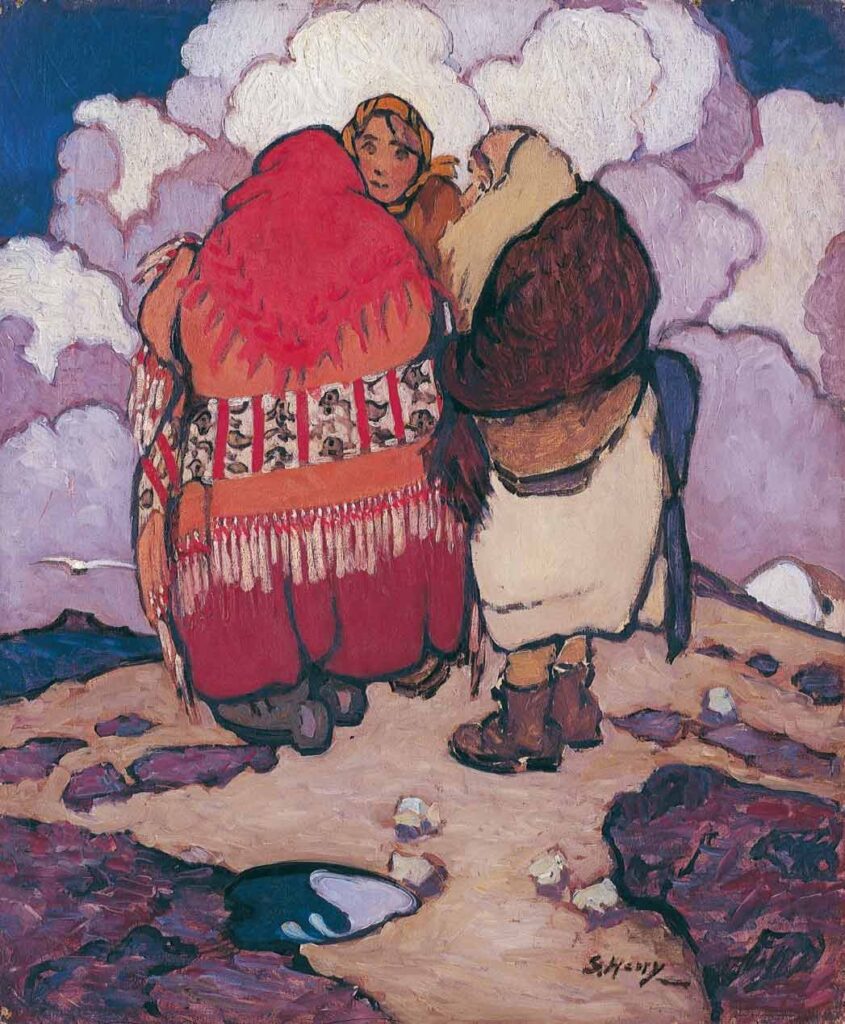

In light of this overlap of professional aims and experiences, the artworks reveal many synergies between Irish and Australian women artists, particularly academic still lives and portraits and the later classical modernist work. Landscapes show more differences of colour and terrain between the two countries at a base level, although the comparison is not only between straightforward differences of climate and latitude. The substantial white Australian nationalist symbolic investment in landscape practice, conservative and radical, does not have a parallel in Ireland. If Ireland is to be “encapsulated” at a meta-narrative level in visual art, figure painting seems to register more than scenery.

Lady Beatrice Glenavy, Eire 1907, oil on canvas, 91 x 71 cm, by kind permission of Lady Davis-Goff.

Beatrice Glenavy’s Eire 1907 is perhaps a key “takeaway” image from Journeys. Additionally Eire modulates and extends preconceptions of Edwardian era women’s art and melts demarcations between experimental and conventional art. The main figures reference French artist William-Adolphe Bourgereau’s series of monumental Madonnas and the Christ child. However the formalised art nouveau figure as nation equally references Alphonse Mucha’s images of women as symbols of Slavic culture, which were beginning to take over from commercial art in his practice. Both of these sources were widely available to Beatrice in art publications of the time, if she had not seen them in Paris. There are many references to the Celtic revival and the concomitant Irish Nationalism, including the carved early Christian cross and the iconic crescent cloak pin fastening the green robe, that dates back to pre-Christian Celtic art. However a darker layer of historical memory is added by the mass of naked people sheltering under Eire’s cloak, a motif that sits outside much mainstream iconography of c1900. Their clearly visible suffering and vulnerability reads a century or more later as a precursor to press photographs of 20th century mass atrocities and adds a directly political content. The red orange tones at Eire’s feet suggest danger and violence; behind Eire is a shadowy army of saints, possibly martyrs, the ensemble establishing Ireland as colonised, republican, Catholic and suffering, in all a painting with a powerful punch.

Iso Rae, Les Acheteuses (The Buyers), 1913, oil on canvas, 163.8 x 99.5 cm, private collection.

Muriel Brandt’s working class shoppers of the 1940s and 1950s equally locate “Irishness” in its people and their activities, this time ordinary people, but unmistakably speaking of the terroir of place and culture. Many of the Irish paintings show everyday life on the land and in small towns, markets, shorelines and farmyards, but in a less performative manner than Australian depictions of rural life during the same period. Such subjects seemed to interest Australian women less than they did Irish women. Mid 20th century organic expressionism, especially landscapes, but also figurative subjects, are more visible and prevalent in Journeys than in Australian art historical constructs. This style of painting certainly can be seen in Australia in the work of artists such as Eva Kubbos and – for periods of their working life – Nancy Borlase and Jean Isherwood, and many others male and female. A crucial documentation of the importance of such expressionist landscapes in Australia are public collections. Particularly works that won the acquisitive Mosman Art Prize, founded in 1947, in its early years and the early acquisitions for a number of the New South Wales regional galleries document this style’s reach in 1950s Australia. Although it has slipped out of curatorial notice, this organic expressionist view of landscape painting seemed to flourish particularly in New South Wales and Queensland. Conversely there are elements of Australian art, such as the personal rawness and female-centric narratives of Joy Hester’s works on paper, that have no translatable pendants in Irish art of the same generation. Likewise Indigenous Australian art takes the collected images of Odd Roads into a vastly different space.

Odd Roads usefully reminds us that artworks from the interwar generation of women artists remain as pleasing and attractive in troubled and difficult times as they have been to readers and gallery visitors since Australian researchers 45 years ago began to make early to mid 20th century Australian women artists and their images accessible to the public via texts and exhibition projects. In this context of the near-half century of engaging with Australian women artists of the past, and in the context of the increasing “presentism” of a public sphere dominated by the short cycle of social media and framed by an amnesia around everything beyond an adolescent lifespan, we should acknowledge the compounded achievements of many artworkers in the mid to late 1970s who engaged with the then virtually invisible body of work by non-living artists. Curators such as Nicholas Draffin and Roger Butler uncovered the significant role played by interwar women printmakers in extending aesthetic options in Australia [viii], Suzanne Davies and Janine Burke worked on the Ewing and Paton Gallery’s 1975 survey of historic women artists, Anna Sande and Bonita Ely with funding from the Schools Commission in 1977 researched women’s art in gallery storerooms and early Australian publications for the Women’s Art Register to provide new and more inclusive curriculum materials for schools.[ix] Jude Adams, Barbara Hall and Jennifer Barber presented the first modern curated survey of women artists organised by a state gallery, Women’s Images of Women at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1977 [x]. Humphrey McQueen’s Black Swan of Trespass 1979[xi] put Margaret Preston at the centre of Australian rapprochement with modernism. This text, which remains somewhat unfamilar to present day activism, shifted scholarly emphasis away from the basic timeline established in Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting 1962 and parallel texts by Roberts Hughes and James Gleeson that similarly claimed to capture the “whole” narrative of “Australian” “art”. This existing norm was set as white and substantially male; it focused on easel painting, with an occasional glance at sculpture. This body of early feminist research and curating established the baseline for what is approaching half a century of research and advocacy amongst curators and academics, as well as dealers and collectors.

Grace Henry, Top of the Hill, c1920, oil on linen, 60 x 50 cm, Limerick City Gallery of Art.

Having started to review both titles together in mid-2020, the climate of cultural and social life against which the work of reading and writing unfolds has radically changed. However in my opinion the historic artworks to be seen in both books have not yet been, in current terms, “cancelled” but stay relevant and robust. If we are living in the “interesting times” of the faux, or at best misread “Chinese curse”, “may you live in interesting times”, [xii] the works of women artists c1900 to 1945 still seem to speak of an idyllic era of good fortune for the independent and relatively well-off creative woman. Favorable opportunities, newly accessible professional resources and expanding social freedoms for women launched many careers in Australia and Ireland, as the work of Paul Finucane and his collaborators Catherine Stuart and Maria Connolly document. How different is the situation that many Australian women artists find themselves in today. Living from project to project and via a pottage of small contracts, supplemented by casual work in other sectors, many women have been directly affected as the economy contracts and public movement has been restricted. [xiii] Moreover artworkers can find little support in financial relief “packages“ that make no provision for characteristic patterns of work and income streams often seen in the creative sector in Australia, including multiple project, prepaid and contract based earnings.

Creative and thinking work no longer feels the same as it did in the previous year. Lenin apparently coined a phrase about “weeks when decades happen”. 2020 brought many of these. COVID-19 manifests as the unnerving, change-broking wallpaper to everyday life. Australia already entered 2020 in a state of widespread physical and psychic trauma triggered by a bushfire season of unprecedented recorded ferocity and scale of geographic distribution. Then in late May the Frankie Magazine life of sourdough baking and raiding the fabric stash for new projects fell apart as nightly news began showing civic unrest in the US and Hong Kong. [xiv] In some countries people are taking to the streets, protesting necessary lockdowns of public space and commercial activity including right wing civil disobedience in the United States that places individual comfort and freedom above collective public safety.

Civil unrest and the growth and deconstruction of the nation state, both imagined and actual, is not alien or irrelevant to Paul Finucane’s researching and assembling of art historical biographies. Whilst everyone is familiar with the usual excuses of patriarchy or the “women can’t paint” argument, the 20th century history of Irish independence and the building of an independent nation and identity also made Irish women artists of the early and mid 20th century alien and outlying cultural entities. The story loops around into the present because in the early 20th century, along with the suffragette movement and the complex ethnic and cultural divides of the eastern Balkans and the edges of the Ottoman empire, the rise of the Irish Free State established popular understandings of political activism within the state and the political system that remain live and viable today.

My view is that Irish women artists of the 20th century had a fairly antagonistic or even hostile relationship with the art establishment even before the Irish War of Independence and the formation of the Irish Free State. I am further of the view that the new Irish Free State created an even more hostile environment for women artists who were predominantly from aristocratic, urban and Protestant backgrounds at a time a new sense of national identity celebrated/promoted the ideal of the ‘noble [Catholic] peasant’. This of course is a personal view. [xv]

Kathleen Fox, The arrest 1916, oil on canvas, 56 x 76.5 cm, The Model, Sligo.

Irish politics and nationalism, as well as pushing many women artists out of the public eye, also shaped their practices, taking them in directions far removed from experiences of women artists working within “settler culture” in Australia. Kathleen Fox offers the most obvious and extreme distinction between the experience of Irish and Australian women artists. Her painting The Arrest 1916 was painted in secret and sent to New York for safe keeping. She had made sketches and preliminary studies as a direct witness of the surrender of the Stephens Green Garrison to the British Army on 30 April 1916. The British government, one of the most repressive of all major players in the First World War to their civilians, regarded the uprising as high treason and artwork sympathetic to the cause would be, at the least, censored. Kathleen Fox also painted the Irish Civil War during the 1920s. As live action scenes (unlike much of the work of other women painting subjects of the First World War) and political statements these paintings have a significance to a larger discussion of women’s art history. They are beyond the still tenacious stereotype of women’s art being cosy, domestic, passive and basically irrelevant. Yet whilst she knew many of the founders of the Irish republic personally and clearly was sympathetic to the republican cause, her upper-class family had a long association with the British military. During the First World War her brother won a DSO as major of the Scots Guards. In 1917 she would enter a brief marriage with a British officer who was killed at the front within a year. When thinking of Australian art history, Kathleen resonates; artist Hilda Rix Nicholas would also marry an officer during the war and be soon widowed in Britain in an even shorter space of time, one of the many close parallels between the experience of Irish and Australian women artists. This disjunctive family situation between British and Republican loyalties was “not unusual” in early 20th century Ireland according to Paul Finucane and Maria Connelly[xvi], although not prominent in popular memory.

Yet Kathleen Fox’s lived contradictions and the personal decisions that she made to accommodate these also speaks of the links – in this case antithetical – to the volatile, universal politics of the present, where conflicting views no longer cannot exist concurrently but only exist in a “zero-sum game” where the right obliterates the wrong and one party’s gain is at the expense of another’s loss. However the past is more complex and contrary than present cultural constructs may claim. Many diverse agents and their choices and actions are obliterated in simplifying the parameters of creativity to fit an argument. Research and empirical narratives, well exemplified in Journeys and Odd Roads, are the quiet, non-self glorifying pushback to a limited and half-told story that is certainly erroneous in itself, but wrongly assumed to represent the whole of the past.

Gladys Reynell, Old Irish couple, 1915, oil on canvas, 65.3 x 54 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Whereas once the artists documented in Journeys and Odd Roads were marginalised by gender, now the genial, non-confrontational aspects of their practice threatens to push them back into the sidelines. Are they dissonant to a new public vision of artmaking? Here creative and intellectual workers are categorised as “good” or “bad” and thus their suitability for public cultural endorsement is a corollary to their moral worth.[xvii] In current public culture political statements are paramount. Along with rapid and structural shifts in social values, “culture is shifting and we are witnessing reckonings across the screen industries, academia, publishing, journalism, music, food, fashion and visual art”, say Hannah Reich and Beverley Wang for the Australian Broadcasting Commission. [xviii] Yet if culture is diversifying racially, concurrently it is growing narrower, focused on the present and on the values of younger people, even more fervently and exclusively than in the 1960s. Moreover public debate now has a far less confident grip on reality or objective analysis, often relying upon memes, myths and half-truths, especially if they confirm biases, when criticising of others’ stances.

If Kenneth Clark believed that art history could be encapsulated as a continual tacking between classicism and romanticism, or expressionism and formalism [xix], we seem to be surfing a flow-tide, if not a tsunami, towards a new Calvinism, where creativity seems to exist only for a moral purpose. Whereas for a century and a half, the avant garde identified itself against the 19th century contention that art existed to deliver a moral lesson or an enjoyable story, suddenly artworks are primarily functional again, with no presence beyond their roles as communicative devices. Design, materiality or visual appeal are no longer important. It matters little that Antoine Mercie’s sensuous handling of bronze, alongside that of Rodin, fostered a revolution in late 19th century sculpture: his Robert E Lee statue in Richmond, Virginia can be nothing other than an abomination in the public space. It offers nothing beyond the urgent need to remove it.

Academics and curators, at least in the United States, accept this volte face against accepted cultural practices without comment or analysis. They eschew the underlying drivers of such key theoreticians of the past as Baudelaire, Huysmans, Pater and Wilde for example, who sought to divorce art from theology or morality and laid the foundation of a century and a half understanding of the avant garde. African American essayist and cultural theorist Thomas Chatterton Williams, who organised a recent controversial letter in Harper’s Magazine condemning the aggressive and combative practices of current cultural debates, itself immediately disputed by those who opposed his stance [xx], defends the concept of “a universal artistic statement” or “art for art’s sake” against the charges that it “is a kind of iteration of white supremacy … a white, patriarchal imposition.” [xxi]

Yet can history be the weapon against cultural erasure as much as the oppressive barrier that blocks diversity? The website Forbidden Music by Michael Haas presents biographical and archival research into composers and other musical professionals who were persecuted during the Third Reich. He collates fascinating biographies and supporting documents, backed by meticulous historical research, combing through archives, interviewing families, colleagues and even first hand statements by a few survivors. This generation of central European creatives was a persecuted minority, dismissed from professional appointments, forced into exile, their work banned and their assets confiscated. Many lost their lives in the Holocaust. Others made a range of willing or unwilling compromises with the Nazi regime – and later sometimes Eastern bloc regimes – in an attempt to protect and consolidate their careers. Ironically the victims of the Third Reich were as thoroughly negated by anti-fascism and the post-war avant garde as they were by the actual fascists during the Nazi era. Thus Haas’s project resonates far beyond Holocaust studies into current ways of “doing culture”, although anyone who has studied women artists knows that respected and sometimes radical institutions, values and art professionals censor art and artworkers as much as does the right wing.

Haas’s validation of large compass but fine-scale research projects, the importance of retrieving not only the work itself but the context in which the work was produced and understood, affirms not only the work of Paul Finucane and his collaborators Catherine Stuart and Maria Connolly, but also my own work for Sheila Foundation and other organisations across three and half decades, if we shift Haas’s discussion from music to the visual arts –

For every “great” composer, there were any number of others who enjoyed equal success in their lifetimes.

…. it’s important to create a comprehension, (which is slightly more than understanding, or mere acceptance) of the macro-environment in which a composer’s unique creative impulses thrived. This [is] only possible once a critical mass of works had been uncovered and a critical amount of research had been undertaken. This need to comprehend creative environments applies as much to Handel and Bach as it does to Xenakis and Legeti. [xxii]

Odd Roads and Journeys provide that “macro-environment” of women’s art making in both Ireland and Australia and allow for some fascinating unexpected crossovers as well, which build up the collective relevance of whole generations of artists. If Michael Haas can argue that research enables better understanding of an expanded canon

In short, musicology and historiography help create the biotope of creativity, and with that comes understanding and appreciation among audiences and performers [xxiii]

then Odd Roads and Journeys open up that same path to knowledge and appreciation, and simple curiosity and enjoyment, which reforms and transcends limited and discriminatory cultural models. Rather than cancelling, deplatforming, anger and destruction as culturally central, we need more opportunities to see more artists’ works and read their backstories.

[i] Comment by Paul Finucane in email to author

[ii] Elizabeth Hanks Australian art and artists to 1950: a bibliography based on the holdings of the State Library of Victoria Melbourne: Library Council of Victoria, 1982. Caroline Ambrus The Ladies’ picture show : sources on a century of Australian women artists Sydney: Hale and Ironmonger 1984

[iii] Kerr, Joan. And Callaway, Anita, eds Heritage. Sydney: Craftsman, 1995.

[iv] David Ellis A women of no importance The Age 2 May 2007 https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/a-woman-of-little-importance-20070502-ge4skl.html

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Irish_R.M.

[vi] Depending on how definitions are drawn Constance Gore-Booth may be the first woman to serve in an executive function in any Western state, outside of hereditary royalty or de facto engagement by consorts of leaders such as Eliza Lynch in Paraguay. However Gore-Booth Markievicz was preceded by Alexandra Kollontai as a commissar in the 1917 Russian Bolshevik government. Other women such as Nadezhda Krupskaya also held considerable executive power in the same government. In 1918 Markievicz was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons but refused to take her seat as a political protest.

[vii] Irish modernist architect and designer Eileen Grey also shared this background coming from a wealthy Anglo-Irish Protestant family

[viii] Nicholas Draffin Australian Woodcuts and Linocuts of the 1920s and 1930s Melbourne: Sun Books, 1976. Roger Butler The Prints [of Thea Proctor]; Introduced and Catalogued by Roger Butler. In Chris Deutscher (ed). Thea Proctor:The Prints. Sydney: Resolution Press, 1980.

[ix] A Profile of Australian Women Sculptors, 1860 – 1960, (inc. slide kit), Women’s Art Register, Melbourne

[x] Project 21 – Women’s images of women (1977), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 15 Oct 1977–13 Nov 1977

[xi] Alternative Publishing Cooperative, 1979.

xii Although widely described in many cultures as an ancient Chinese curse, the phrase seems to date from the late 19th century and early 20th century and was used by the Chamberlain family of British politicians. It may have some relationship to a documented 17th century Chinese quote from a poem “ Better to be a dog in times of peace than a human in times of war”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_you_live_in_interesting_times, https://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/12/18/live/

[xiii] Research is showing that women’s work and finances are more affected than men’s in the wake of Covid19 Wendy Touhy “Calls for female-focused budget as women face financial ‘gender disaster’ The Age August 16 2020 https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/calls-for-female-focused-budget-as-women-face-financial-gender-disaster-20200815-p55m0e.html

[xiv] Juliette Peers “ Rewriting” in Women’s Art Register Bulletin no 66 2020 p 42

[xv] Comment by Paul Finucane in email to author

[xvi] Through Line and Colour: Forty Irish Artists of the 20th Century p 45

[xvii] https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/useful-idiots-taibbi-thomas-chatterton-williams-cancel-culture-bari-weiss-nyt-1030497/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MijFtGQYowg around 1.10

[xviii] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020- 07-14/racism-whiteness-culture-arts-media-black-lives-matter/12443358 Arts and media reckon with racism and inequality amid Black Lives Matter movement

[xix] As set out on his television series (1973) and book The romantic rebellion: romantic versus classic art London J. Murray, Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications Ltd 1973

[xx] https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/7/22/21325942/free-speech-harpers-letter-bari-weiss-andrew-sullivan

[xxi] https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/part-of-a-larger-battle-a-conversation-with-thomas-chatterton-williams/

[xxii] https://forbiddenmusic.org/2020/03/28/musicology-and-the-music-business-a-personal-journey/

[xxiii] https://forbiddenmusic.org/2020/03/28/musicology-and-the-music-business-a-personal-journey/