With the Cruthers Art Foundation transitioning from a private to a public entity, it is timely to continue the discussion around private collections entering the public realm started in Blog 3 in April 2017. Featuring an interview with curator Gemma Weston, this blog explored these issues in relation to the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia.

Image (banner): The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, photo: R. Kennedy for Visit Philadelphia

Naturally given the high level of private philanthropic support for the visual arts and the public gallery and museum system in the United States of America, that country provides many examples of private collections evolving from donors’ original gifts into public institutions. The range of challenges and complications that emerge as collections and bequests grow and develop offer substantial insights into the fate of private art collections and foundations, once they leave the direct custodianship of their original supporters. Some collections change radically as the years pass, as the wishes and preferences of those who set them up become increasingly distant and faded in public memory. Ironically, and perhaps sadly, such fading often and substantially occurs in the minds of those trustees and museum professionals who are primarily charged with advocating for the donor’s original vision.

Perhaps the most high-profiled and fraught example of a private collection’s complex fortunes after the death of its founder is the Barnes Foundation of Philadelphia. Medical doctor, industrial pharmacist and visionary collector, Albert Barnes (1872-1951) left a will that stipulated a collections management system that was, already in 1951 at the time of his death, far outside standard practice. Today his collection of European impressionism and modernism remains mind-blowing, even when judged against other North American public galleries or indeed art museums globally. He owned 181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, 59 Matisses, 46 Picassos and so on. Some of the artists whose works he collected, including Matisse, were personally known to him. When confronted by artworks he did not understand or recognise as valid, Barnes proactively immersed himself in the developing theories of the early twentieth-century avant garde, formalism and non-representation. Far from saying that a five year old could make better art than trend setting Europeans, Barnes became a pugnacious, one-eyed advocate for modernism.

Opening his collection to the public in a specially built education centre, he laid down detailed protocols. He mandated strict caps to visitor numbers and restrictions upon photography, especially in colour, and forbade lending and touring of works, hosting temporary exhibitions in his galleries and any changes to the dense eclectic salon hangs, which he had himself designed. The displays blended European modernism, African art, Asian art, Native American art, early American folk art and even early industrial objects from American and European cultures. Shared formal design and material synergies or sometimes purpose and function offered cross-cultural conversations. Only during the last two decades, in the wake of post-colonialism and the decolonisation of knowledge and culture has Barnes’ approach become far more mainstream in galleries and museums in order to break the 19th century division of artworks by period and race.[i] Whilst Barnes’ name is now a byword for idiosyncratic, even bad, practice, some of his “deviations” look uncannily like what is now being hailed as cutting edge in other contexts.

In Hobart, the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) offers a fascinating parallel to the Barnes Foundation. MONA makes much of the founder’s strong hand in the collections and hangs. The gallery’s highly individualised displays and the activities and opinions of the founder thus become a drawcard.[ii] Possibly MONA wins more hearts and minds because the non-standard provisions and the founder’s strong thumbprint are marketed as kooky and liberating, with a Rabelasian, Bacchic mojo, whereas Barnes’ radical gestures can be superficially read as repressive and constricting, as they are more cerebral and theoretical. Across eras and continents, Albert Barnes and David Walsh of MONA have many things in common: strong personalities, commitment to the avant garde, art purchases that are densely and thoroughly thought through and are linked to an overall program they devised and passionately seek to share with the public. Above all both men had the financial resources to make their highly personalised, big-picture vision of the ideal art museum a reality, without having to compromise by co-operating with or seeking the favour of gate-keepers or established players.

The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), Hobart.

A series of bitterly contested legal actions brokered significant changes in Barnes’ provisions from the 1990s onwards. A protest documentary, The Art of the Steal, (2009, directed Don Argott) details the protracted series of legal actions. Initial legal challenges to Barnes’ template for his museum had begun in the 1950s, soon after his death. Today the situation of the collection is far different to when Barnes was alive. The collection has been relocated, has toured and been loaned. It is now widely documented in colour photography. Barnes’ hangs have been reassembled in a new venue[iii] that also replicates the proportions and layouts of the rooms that he designed, including one with a custom-designed frieze by Matisse, purposely commissioned for the space, that itself has been reinstalled. Some of Barnes’ provisions remain: photography by individuals in the galleries is still banned and entrance is still ticketed every day to stop the galleries becoming overcrowded as he desired. Comfort and space in the galleries were important to Barnes as he wished to optimise visitors’ intimate dialogue with the original artworks.

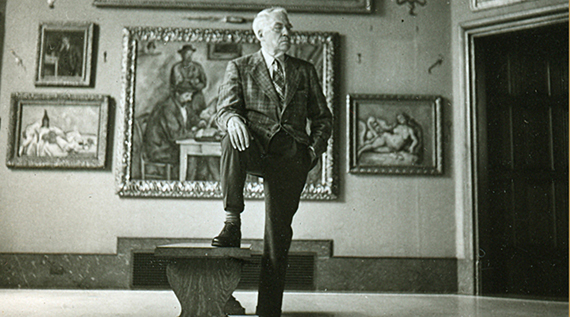

Albert Barnes in Don Argott’s The Art of the Steal (2009).

Meanwhile in Australian universities thousands of kilometres from Philadelphia and decades after Albert Barnes’ death, Barnes Foundation holdings were once only shown as black and white images in art history lectures and tutes, until the 1990s brought in the substantial challenges to his will. Barnes’ intense dislike of colour photography of works of art and printed colour reproductions was due to the limitations of early twentieth-century colour photography technologies and equally the limitations of three-colour offset printing, then in its infancy. The outcomes of both processes in the early 1900s were nothing like the perfected technologies in colour photography and printing that became standard in the post Second World War era (albeit having had a long development process). Other colour printing technologies that Barnes would have known, such as chromolithography, distorted the artwork even further, relying upon the image being totally redrawn by another hand in order to be reproduced.[iv]

These contestations around the Barnes Foundation have led it to become widely discussed by both academics and journalists in the multiple contexts of art history, curating, museum studies, philanthropy, race relations and legal studies across North America, as well as even being the subject of documentary films and literary and academic monographs.[v] Professional literature and debate offers no clear consensus, an interesting position in the face of the tendency for Australian public collections and curatorial practice to often adopt a substantially unified position, en bloc. Some commentators regard the changes to Barnes’ will as an astute response to social and technological shifts that have ensured the survival of both collection and foundation.[vi] Others conclude that the changes offer a dangerous precedent in the American legal system for undermining donors’ intentions and facilitating poor quality, self-interested practices amongst trustees and staff in public gallery management.[vii] The most doom-laden comments suggest that the high profiled legal cases around the Barnes Foundation and other public art galleries in the United States that have undergone well-publicised crises, such as the Rose Art Gallery at the University of Brandeis, Waltham, Massachusetts [viii], will discourage post-war and baby boomer generations of wealth from gifting to public art galleries.

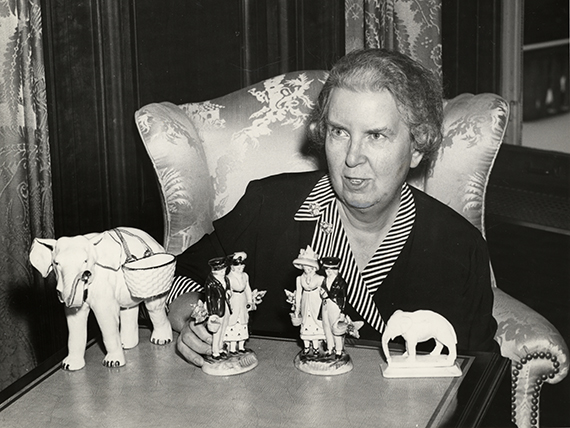

Conversely Margaret Woodbury Strong (1897-1969) of Rochester New York, an heiress to considerable stock in the Eastman Kodak firm, left a will that gave future directors and boards substantial freedom to develop her collections in fresh directions, and to invest and fundraise on behalf of her museum. Established shortly before her death in 1969, her museum was an eclectic and vast assemblage of decorative arts, conservatively estimated to cover at least 300,000 individual items. Her collections were linked by a focus upon the intricate and decorative, and often evoked a spirit of fantasy and camp. Strong’s museum was famed as the largest collection of dolls and toys in the world, but the holdings also encompassed paintings, graphic art, including 85,000 bookplates, oriental art, furniture, fashion and textiles, glass, ceramics, craftwork, miniature objects, popular culture, rare books and even early household appliances.

Margaret Woodbury Strong and her collection.

Unlike the Barnes Foundation the Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum of Fascination, as she wished it to be called, has changed radically, witnessing several major repositionings of its identity and holdings throughout the last five decades. The first major change was to move out of the amiable and intimate site of Strong’s own mansion, cutting the objects off from the personal, private microcosm that was in some ways the raison d’etre for them being together. Rehoused in a purpose built museum facility, with not only display areas but also zones of “accessible storage” as a means of dealing with the vast quantities of items assembled by Strong, curators used the scale of her collections to document changes in middle class American experience from the early 1800s to the Second World War.

In this guise it failed to attract a significant audience and drastic surgery was called for. Market research led the Strong Museum to concentrate on a family and child-based audience in the 1990s, and thus its attendance figures grew.[ix] Equally museum staff recognised how important digital technologies were to new experiences of recreation and play and decided to move into collecting and documenting these media. The museum, now rebranded the Strong Museum of Play, has attained a global importance as a unique, highly interactive museum of recreation, games and play, including digital and computer games.[x] Given the overwhelmingly masculine inflection of electronic games, sports and street cultures, in the US and therefore globally, there is an unacknowledged significant misogynist inflection in the flow-on effect. Moreover many academic and collecting institutions fail to interrogate the gender politics of this widespread unqualified celebration of both street art and digital media generally in modern culture, without even considering a case study such as Margaret Woodbury Strong’s collection.

In the case of Margaret Strong’s bequest, it could be argued that much has been lost. Erased from public life forever is a collecting practice that predated, yet synergised with, second wave feminism. Strong’s unwillingness to critically rank artefacts via traditional connoisseurship and her embrace of the often sidelined experiences, artefacts and materiality of domestic life immediately recall second wave feminism’s intervention into standard aesthetic principles and artworld value judgements. Remarkably, Strong’s collecting simultaneously evoked third wave feminism via its celebration of the camp and performatively artificially feminine. In comparsion to the Barnes Collection there has been little public contention about the changes to or professional defence of the founder’s idiosyncratic vision.[xi] De-accessioning such items as vintage shop mannequins, confectionery packaging or glamorous art deco dressing table ornaments, as irrelevant to “play” or collective popular experience, speaks like censorship as much as professional streamlining of holdings. A de facto public statement has been made about the relative worth of female cultural experience and objects. Sometimes the statements made by Rollie Adams. the director, who led the shift of direction of the Strong Museum display a certain insensitive humour: “Actually we have been de-accessioning ever since Mrs. Strong died – she left a bunch of stuff.”[xii]

Another similar curatorial erasure of an extended consciously feminine vision of material culture that comes to mind is the loss of Queen Victoria’s meticulous and obsessive preservation of her own dresses and accessories, often with annotations about when and where worn, a practice that she started as an adolescent and continued until at least the years of her widowhood.[xiii] She also preserved clothing belonging to her children and her mother. Only a small proportion of the original collection survives, mostly garments associated with occasions of mainstream historical importance, which suggests the hand of a professional historian or curator behind the cull. The substantial disappearance of Victoria’s dress collection from public life normalises her reputation and position as a historic figure.

Some third wave feminist scholars in the 1990s suggested that whilst Victoria could be defined as a conservative figure at the zenith of an imperial and colonial pyramid, she often used her anomalous position as a woman at the very centre of the symbolic order to impose feminine values and choices upon figures of male authority in politics, state and church. Her elaborate mourning rituals not only made romantic love and loss a highly visible and central organising pivot in everyday life, but had the abstraction and formality of a theorised contemporary art practice, a fact that Victoria herself seemed almost to recognise.[xiv] Curiously both Strong and Victoria grew up as lonely isolated girls in relative material comfort, but with fairly rigorous, austere maternal supervision and rich imaginative lives, centred on dolls and similar objects. If one argues that no museum or gallery can keep “everything”, against Strong and Victoria’s desire to capture the dissolving moment via material culture, then why has precisely this mode of immersive, wholistic collecting been validated for a masculine mind by the Andy Warhol Museum? Here the artist’s “time capsules”, cardboard boxes of material cleared periodically from his workspace that includes texts, images and objects, have been lovingly inventoried and provide a remarkable social and cultural resource. Selections from Warhol’s “time capsules” have been presented as blockbuster exhibitions in Australia, for example at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2005.

Despite her wealth, Margaret Woodbury Strong’s collecting practices were seen as eccentric and out of line by her contemporaries.[xv] Someone of her economic and social status apparently “ought” to have been collecting “expensive” or “serious” items. An eyewitness said that her house “resemble[ed] a flea market rather than a mansion”.[xvi] The sheer quantities of her holdings of what some regarded as culturally and critically unimportant items also seemed to position the museum outside orderly public gallery and museum norms. “Mrs Strong’s reputation as a ‘frivolous old lady who had a mansion full of dolls and toys’ was according to one report, a negative image locally which the museum staff worked hard over the decade to erase”.[xvii] As a public institution, Strong’s museum needed to be seen to deploy a stronger narrative linking the objects and justification for retention of holdings than the original owner “liking” an item. In focussing on toys and play, not only have the collections been substantially masculinised, but whimsy, play and entertainment have been normalised and corralled as pertaining to childhood and also certain types of educational pedagogies, and quarantined from adulthood. Surely in some ways it is a conservative, neo-liberal construct of age-based behaviours.

Margaret Woodbury Strong and her doll Mabel.

Collections and institutions cannot and ought not remain static. All those involved with public cultural facilities and curatorial, gallery and museum training programs recognise this baseline, as do many private collectors. Blog 3 discussed how the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art may and will shape-shift as it is acclimatised to the very different environment of an institution. Now decision making to purchase is accountable to a wide range of issues beyond an individual being drawn to something seen in a gallery, shop or studio. Yet putting this policy into practice is more complex than textbooks may claim. An implied driver behind the major changes at Margaret Woodbury Strong’s museum has been facilitating the museum to engage a broader range of the community in its immediate locale and across the United States generally, and augment public learning opportunities for disadvantaged children. In effect recent commercial products and trends have sometimes been prioritised over older, often culturally diverse objects because these objects are more unfamiliar to an audience saturated in popular media and culture. Margaret Woodbury Strong herself brought widely and admiringly across many cultures and indeed placed various cultures alongside one another on an equal platform.

This revision of the nature of displays and holdings ironically – even patronisingly – actually limits the options for its targeted audience via choices made by “experts”. Does taming the unstructured optimism of the disorderly Wunderkammer model of the museum or art gallery, where, as with Margaret Woodbury Strong’s personal collection, a wide range of objects were acquired for their emotional and visual impact, their ability to arouse emotions of wonder, awe and engagement, impose a sort of censorship and paternalism? Therefore is it impossible to outrun the baseline post-colonial suspicion of the museum or gallery as a centralising institution that sets agendas and keeps its audiences in place? Museum policy may advocate new social inclusivity or decolonisation of knowledge and present itself as caring and responsive, but does that top-down, leadership-strong enlightened curatorship benefit the supposedly disadvantaged audience or just put them in yet another box with a different label?

The Strong Museum has certainly had a global reach, for example the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has likewise refocussed its displays of child-related objects towards addressing sensory and creative lacks in public education and enhancing the experience of urban childhood, but it appears to have done so without de-accessioning. Archiving and celebrating mobile and electronic entertainment and creative technologies, a baseline of the Strong Museum’s current policy and an area that it pioneered, has also become the purview of specialist facilities such as ACMI, which surfs the volatile interactions between newness, accessibility, relevance and heritage, with emotional adroitness and plurality.

Yet scholars suggest that Barnes implemented his seemingly perversely anti-professional rules to enhance the intellectual and creative experiences of an everyday and diverse audience. This idea of the public institution as having a responsibility to communicate to a non-professional audience, without access to the broad educative resources of the private sector, also has driven and justified the changes at the Strong Museum. Far from being hostile to the general public, Barnes’ mission for the art gallery was to offer formalist aesthetic sensations in professional standard surroundings to working class people, including POC. He was also concerned to prevent his gallery acting as a venue for what he believed was trite upper class amusement and socialising. Supposedly Barnes kept a “black list” of wealthy and prominent people who were to be refused entry to his museum. [xviii]

Barnes, whilst he believed in a traditional connoisseurship and the concept of demonstrable “excellence” in visual art and design, did not associate these values solely with white Anglo-European culture. He believed that mainstream curatorial and art historical practices diminished the awareness and appreciation of other cultures and thus he arranged his artworks from non-European cultures alongside the European avant garde. Vocal opponents of changing his provisions suggest that the Barnes Foundation galleries have been recolonised by the very wealthy and socially prominent groups whose influence upon his bequest he wished to minimise. It was suggested Barnes ceded management of his foundation to an African American college rather than a white university in order to bypass the elite.

In expanding and professionalising a donor’s gift, and moving with the times, Heide Museum of Modern Art has achieved a parallel transformative process of maturation and consolidation as the Strong Museum went through, with perhaps more grace and respect of the vision of its founders, Sunday and John Reed. The shift has respected the choices that the founders made as private agents in assembling a collection, which has been preserved, yet without foreclosing upon expanding future initiatives to engage with shifting understandings of cultural practice and production in the manner of the Strong Museum’s ongoing development.

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, photo: Jeremy Weihrauch.

Changes to art practices and new technologies, unknown at the time of the Reeds’ deaths, have been assimilated with responsive flexibility and grace. A recognition that the local community in which the gallery is sited responds more to the recreational, material and life style elements of the Reeds’ vision – the garden, the spacious grounds, the kitchen, cooking and entertaining – rather than their commitment to transformative new art, has allowed for the broking of links and support networks, unthought of in the direct model of the Reeds’ support of modern art since the 1930s. Yet simultaneously, the commitment to extended and original scholarship that continually sets benchmarks for professional and industry peers has been maintained. Programs such as the Albert & Barbara Tucker Gallery, devoted to the work of a single artist have been developed in a rich and thoughtful manner, that rather than constricting becomes insightful and value-adding, extending public understanding of the artist and the institution’s reputation for scholarly originality.

In some ways Heide and the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art have a far easier mandate than the Museum of Fascination, as Margaret Woodbury Strong imagined it in the 1960s. Both have the base-line marketing necessity of a clearly identified mission/function well in place, from the gift and choices of the original donor. One could hope that there is not much incentive to radically change organisations that are – at least to outsiders – functioning effectively and responsibly. Ironically the relative limitations of scope within the private arts funding sector in Australia, and the still relatively benign (at least in relation to the United States) litigious climate in this country, may currently lack the vitality of the US sector, but somewhat protects entities like Heide, MONA and the Cruthers Collection from the spectacular anxieties and contestations around the Barnes Foundation. Certainly aspects of North American culture have contributed to the complex afterlife of Barnes’ Gallery and Foundation. The particular combative theatrics of the American legal system certainly fosters a certain degree of speculative aggression that has begotten the challenges to Barnes’ will. Moreover if not every extremely wealthy person in the United States claims to be informed about art, the practices of sitting on boards for public gallery governance and fundraising, or being seen to be involved with such matters – think of the annual Met Ball – have long been part of the public rituals and signifiers of upper class life. There is a large potential pool of campaigners both qualified and willing to step into the ring and throw a few punches sometimes as much for their own status and reputation than for curatorial or museological ethics.

On the other hand, the changes to Margaret Woodbury Strong’s collection have come from the choices of gallery and curatorial professionals dealing with the objects in the collection. Trustees – including those who are working to their own agendas – certainly impact upon the directions that a collection takes after the owner’s guiding hands (and heart) have departed, but so do curators. Perhaps the Strong Collection as case study indicates that industry-based acuity sometimes pales besides the divine madness of the independently minded private collector. Yet the speculative and outlying purchases of the Cruthers Collection from Freda Robertshaw and Elise Blumann to Narelle Jubelin, Julie Dowling and Sera Waters indicate that private collections are enhanced rather than diminished by non-standard purchases.

The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art launch event at Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, The University of Western Australia, Perth, 8 March 2008.

Not all “new” or “innovative” curatorial modes create havoc with older concepts. Barnes’ focus upon formal and design values as a means of understanding and classifying art has now been translated into a computer program which allows visitors to the foundation’s website to sort and organise images of the collection through keyword searches on chosen formalist themes and allows for the blending of multiple themes when searching for artworks. One of the sites of divergent opinion around the Barnes Foundation is defining where the “spirit “ and “intention” of the donor lies. Can the DNA be read from the specific legalistic jargon once approved by the donor, or is it located in a broader catchment of values and beliefs, played out in actions and choices during the donor’s lifetime? If one concludes that the most useful lens for viewing a donor’s ultimate motivation is the interpretative truth offered by analysing a collector’s habits and opinion, then that hypothesis raises the specific vulnerabilities that have beset the Strong Museum.

Here it could be argued that the original assessors of Margaret Woodbury Strong’s collection made no acknowledgement of the strident criticism of public gallery and museum policies then being raised by the emergent second wave feminist movement in the United States in the early 1970s. Later in the 1990s this blindspot to gender and selective bias in assigning value based upon gendered norms jumped a generation when curators and staff used these original reports to in effect erase the original donor’s personality through nullifying her collecting choices. The loss of Margaret Woodbury Strong’s particular charisma and hedonism in her collecting choices is – at least to this present writer – something of a diminishment to the museum that she founded, no matter how exemplary its current global role may be in documenting digital cultures. There would be howls of protest if staff turned MONA in Hobart into a museum of office equipment, but performative feminine camp was seen as acceptably sacrificial and deserving of upgrading and rationalisation to become a professional entity.

Can we read in the shifting contents of the Strong Museum a warning about the fragility of the highly individual fingerprint of the private collector within the public gallery industry? Turning to Australia we can look at the galleries supported by the gifts of such very different personalities as David Walsh, John and Sunday Reed, Albert and Barbara Tucker and Sir James and Lady Sheila Cruthers and express a hope that no bureaucratic systems player will ever seek to fully iron out and normalise the particular personal choices that have shaped these institutions.

Not all “new” or “innovative” curatorial modes create havoc with older concepts. Barnes’ focus upon formal and design values as a means of understanding and classifying art has now been translated into a computer program which allows visitors to the foundation’s website to sort and organise images of the collection through keyword searches on chosen formalist themes and allows for the blending of multiple themes when searching for artworks. One of the sites of divergent opinion around the Barnes Foundation is defining where the “spirit “ and “intention” of the donor lies. Can the DNA be read from the specific legalistic jargon once approved by the donor, or is it located in a broader catchment of values and beliefs, played out in actions and choices during the donor’s lifetime? If one concludes that the most useful lens for viewing a donor’s ultimate motivation is the interpretative truth offered by analysing a collector’s habits and opinion, then that hypothesis raises the specific vulnerabilities that have beset the Strong Museum.

Here it could be argued that the original assessors of Margaret Woodbury Strong’s collection made no acknowledgement of the strident criticism of public gallery and museum policies then being raised by the emergent second wave feminist movement in the United States in the early 1970s. Later in the 1990s this blindspot to gender and selective bias in assigning value based upon gendered norms jumped a generation when curators and staff used these original reports to in effect erase the original donor’s personality through nullifying her collecting choices. The loss of Margaret Woodbury Strong’s particular charisma and hedonism in her collecting choices is – at least to this present writer – something of a diminishment to the museum that she founded, no matter how exemplary its current global role may be in documenting digital cultures. There would be howls of protest if staff turned MONA in Hobart into a museum of office equipment, but performative feminine camp was seen as acceptably sacrificial and deserving of upgrading and rationalisation to become a professional entity.

Can we read in the shifting contents of the Strong Museum a warning about the fragility of the highly individual fingerprint of the private collector within the public gallery industry? Turning to Australia we can look at the galleries supported by the gifts of such very different personalities as David Walsh, John and Sunday Reed, Albert and Barbara Tucker and Sir James and Lady Sheila Cruthers and express a hope that no bureaucratic systems player will ever seek to fully iron out and normalise the particular personal choices that have shaped these institutions.

- Medium also was a means of sorting and grouping exhibits in a traditional museum and gallery “hang”, with items in glass, wood, metal etc also displayed closely together.

- See for example Richard Flanagan, “The gambler: At home with David Walsh” The Monthly February 2013 pp 16-27.

- The original site is now used for an arboretum and study centre for plants, supported and developed by Barnes’ wife Laura, who established a horticultural school in 1940.

- One exception to his antipathy to reproductions of artworks was his African sculpture collection, which certainly looked dramatic in black and white photography, but also circulating photographs of African art had important political functions in Barnes’ opinion. Firstly their beauty and importance would counter North American white racist stereotypes about people of colour and secondly the quality of African art would inform African Americans about the strength and complexity of their originating culture as a means of underpinning their moves towards social equality. Barnes made photographs freely available to the African American press and also sent publications and images to African American schools and colleges. Alison Boyd “The Visible and Invisible: Circulating Images of the Barnes Foundation Collection” in Eva-Maria Troelenberg, and Melania Savino eds. Connecting Gaze and Discourse in the History of Museology Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co 2017 esp pp 143-147

- Amongst these are Howard Greenfield The Devil and Dr Barnes, New York: Penguin Books 1989, John Anderson Art Held Hostage New York: Norton 2003 . Mary Anne Meyers Art, education, and African-American culture Albert Barnes and the science of philanthropy 2nd edition London Routledge, 2017. Neil L. Rudenstine The House of Barnes: The Man, the Collection, the Controversy Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2012, written by a Trustee of the Barnes Foundation, The House of Barnes seeks to present a balanced and non-sensational viewpoint.

- Charles Fried “Original Intent” Green Bag Online vol. 16, no. 2 Winter 2013 pp 127- 133 http://www.greenbag.org/archive/green_bag_tables_of_contents.html. The author is a professor of law at Harvard University and a former Solicitor General of the United States 1985-1989 and Associate Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, 1995-99. He argues that changing the provisions of Barnes’ will protected his foundation and artworks from financial ruin and honours Barnes’ artworks as symbolising “the sacred traditions at the heart of Judeo Christian civilisation”

- For a critical stance see Chris Abbinante “Protecting “Donor Intent” in Charitable Foundations: Wayward Trusteeship and the Barnes Foundation” University of Pennsylvania Law Review Vol. 145, No. 3 (Jan., 1997), pp. 665-709

- The Rose Gallery, which had a well-regarded collection of contemporary art, was earmarked for closure with the auctioning of the total holdings in 2009 in order to raise money to offset the effect of the GFC on its host, Brandeis University, but reprieved in 2011 after many protests including from donors and their families. See Kacey Bayles “Restructuring the Art World: An Examination of Controversial Museum De-accessioning Practices in the Current Economic Climate” NYSBA Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal Vol 20 no 2 Summer 2009 pp 37- 51. This article also discusses the Barnes Foundation and is somewhat critical of North American art museums’ growing choice of de-accessioning as preferred option.

- For the history of the Strong Museum see Warren Leon “The Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum: A Review” American Quarterly Vol. 41, No. 3, September, 1989 pp. 526-542 and Interview with Rollie Adams in American Journal of Play Vol 5 no 2 Winter 2013 pp 135-156. The decision to concentrate on “play” was also based upon reports written in the early 1970s by various museum professionals in the USA that suggested this theme as a means of making Strong’s gift look and behave more like an actual museum.

- Binx Brown It’s Dangerous to Go Alone: Understanding How Museums Preserve and Exhibit Video Games A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2017 p 45.

- The only occasion when substantial de-accessionings at the Strong Museum captured public attention was when the museum sued a small regional auction house for not recognising the importance of a Chinese vase once bought by Margaret Strong, which the museum later consigned for auction. The same vase subsequently sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for over a million US dollars. Incidentally the extreme value of this item also suggests Margaret Strong’s acumen as a collector. See Anon “Museum sues as $23,000 vase makes $1.55m”. Antiques Trader Gazette 28 July 2003 https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/news/2003/museum-sues-as-23-000-vase-makes-155m/

- Rollie Adams director of the Strong Museum quoted in Kathy Quinn Thomas “Museum sells art at auction for $1.7 million” Rochester Business Journal Vol. 19, no. 50, March 12, 2004 via pro quest.

- Relatively little information about this loss is accessible, although captioning at Kensington Palace does mention that the collection has been dispersed at some date prior. Aneira Davies ”Things You Didn’t Know About Queen Victoria’s Fashion” Good Housekeeping October 7 2016 http://www.goodhousekeeping.co.uk/fashion-beauty/fashion-news/things-you-didnt-know-about-queen-victorias-fashion also notes that the collection, once vast, is substantially lost and not many items survive, but an annotated scrapbook with offcuts of the lost dresses has been kept. Underwear including stockings frequently appears at auction, having been passed down independently from the dress collection itself. Victoria, like many wealthy women, owned underwear in vast quantities, ordering items by the gross but wearing each item on limited occasions, if at all. This hardly-worn clothing was often passed onto servants and thus was further dispersed through them. Queen Victoria’s black mourning dresses, which formed the sole content of her dress purchases for the last four decades of her life, with the exception of some coloured shawls, scarves and wraps have been scattered around the world and even the West Australian Museum holds one in Perth

- See the work of Margaret Homans Royal Representations: Queen Victoria and British Culture, 1837-1876 University of Chicago Press 1998

- Emily Morey “Strong mansion was too small for collection” Democrat and Chronicle September 17, 2015 https://www.democratandchronicle.com/story/news/2015/09/17/strong-mansion-too-small-collection/72068488/

- Rita Reff “A World of Fantasy” New York Times October 24 1982 http://www.nytimes.com/1982/10/24/arts/antiques-view-a-world-of-fantasy.html

- Some scholars have suggested that part of the furore directed towards the trustees of the Barnes Foundation when they wished to vary the terms of the bequest may in part have been a racist objection to the composition of the boards of trustees and racist assumptions about their a priori competency or lack thereof. Dr Richard Glanton, then chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Barnes Foundation sued various neighbours of the Foundation’s headquarters for racial discrimination in 1995 due to their opposition of changes that he proposed to make to Barnes’ provisions Rudenstein pp 161-162. Andrew Solomon’s review of Anderson’s Art Held Hostage in the New York Times May 11th 2003 http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/11/books/sensation.html identifies the “acutely uncomfortable predicament” where discussions of the Barnes Foundation veer off into racist issues. For his time and class, Barnes had in Solomon’s words “an extraordinary number of black friends”. Rudenstein presents a careful and balanced picture. Barnes resists encapsulation, whilst modern activists may suggest that Barnes’ belief in the “inherent creativity” of African Americans verges on stereotype, although one based on personal observation of everyday life in working class post civil war North America, concurrently Barnes believed that for North America to achieve its true greatness, African Americans needed to be fully integrated into public, social and cultural life. In recent years the Barnes Foundation has curated exhibitions of social activism and diverse artists to honour the democratic aspects of Barnes’ philosophy.