FROM PERTH TO PARIS: Recovering one of the true innovators of early twentieth century Australian art

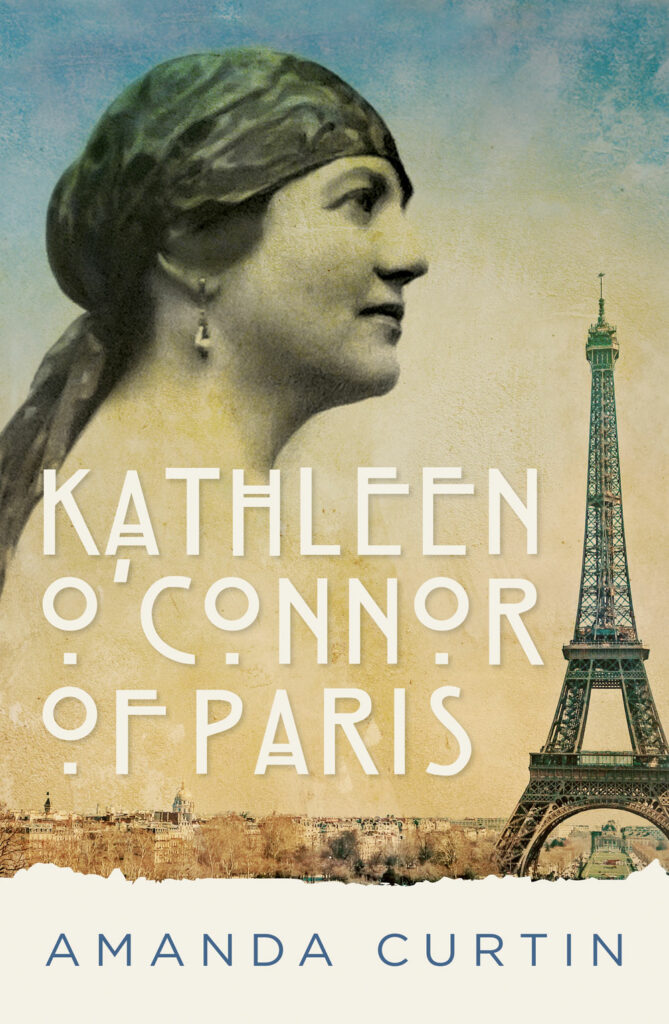

BOOK REVIEW: Kathleen O’Connor of Paris, by Amanda Curtin, Fremantle Press, Fremantle, 2018

By Juliette Peers

“Can you name five women artists?” This question has been a popular grassroots campaign organised for some years by the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC and spread by individuals posting to Facebook and Twitter, challenging friends and family with that question. [i] In 2019 the National Gallery of Australia also belatedly adopted that slogan to encourage more public interest in Australia women artists. One key means by which women artists’ careers and works become better known is via publications. Yet this is a catch 22 situation in Australia. Publishers are generally wary of risking funds and resources on unfamiliar and obscure subjects, which means that women artists rarely come to the attention of commissioning editors, who in turn rarely have art historical knowledge beyond the most obvious and canonical. Moreover when women artists do capture the attention of publishers, the resulting narrative often does not cast them as a working professional. The type of writing matters too. How many catalogues raisonne for Australian women artists are there? Margaret Preston and Bea Maddock are amongst the few women artists given that specialised and intense scrutiny.

Kathleen O’Connor of Paris, Amanda Curtin, Fremantle Press, 2018.

This anecdotalising of women artist’s lives in print is a longstanding issue. John Cruthers in his 2017 review of Gwen Phillips recent monograph Helen Grey-Smith argues that authors writing about women artists provide ought to think out more complex texts than simply pleasant conversations about colourful characters, because it lets down the artist under discussion.

Phillips celebrates the artist’s qualities – her “dignified, independent, full and contented life” – as she quite justifiably should. But the respect and affection she held for her subject may have limited her ability to provide the kind of detailed analysis and objective, carefully weighed overview of her oeuvre that would have been a more telling legacy for Helen Grey-Smith’s not inconsiderable achievements.[ii]

I flagged the same issue in 2000 when outlining the case of Drusilla Modjeska’s popular discussions of women artists from Artemisia Gentileschi to Grace Cossington Smith, and other Australian texts and exhibitions about women artists for the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art.[iii] Here, with widely read texts, the book club rituals of reading and self-discovery and the affirmation of present day cultural values and domestic and personal experiences take precedence over the artist herself.

A case in point is the widespread online praise for a newly published study of a significant Australian woman artist, Kathleen O’Connor. Literary bloggers’ and amateur internet critics’ and readers’ reception of Amanda Curtin’s Kathleen O’Connor of Paris (2018, Fremantle Press) is ecstatic. Across individual blogs, book review and reader’s websites, the reviewers often affirm that O’Connor was, until that point of reading Curtin’s book, unknown to them . The paradigmatic frequency with which this comment is made proves the effectiveness of Curtin’s text as a cultural broker. Equally, the value of any text that introduces the public to the highly distinctive oeuvre of O’Connor, a major figure of the late Edwardian to interwar generation of Australian artists, should not be underestimated. This online phenomenon of discovering O’Connor demonstrates the importance of publishing accounts of women artists. Simultaneously, one may warn both author and bloggers that with great power comes great responsibility. Whilst enjoying the power of presenting their own words to an audience, of being a Pavarotti in their own bathroom, did these writers act with responsibility? This emotively-inflected state of enlightenment and public catharsis of feelings of both admiration for and self-identification with the talented-but-ignored Kathleen and even more with the initiative, skill and celebrity of the published author, Amanda Curtin, could also be seen to elbow O’Connor off the stage. This ritualised confession of ignorance of O’Connor is also ill-informed, given that there have been two previously published professionally researched and detailed treatments of O’Connor’s life and work.

Luxembourg Gardens, c 1912, oil. Courtesy of The Wesfarmers Collection of Australian Art, Perth.

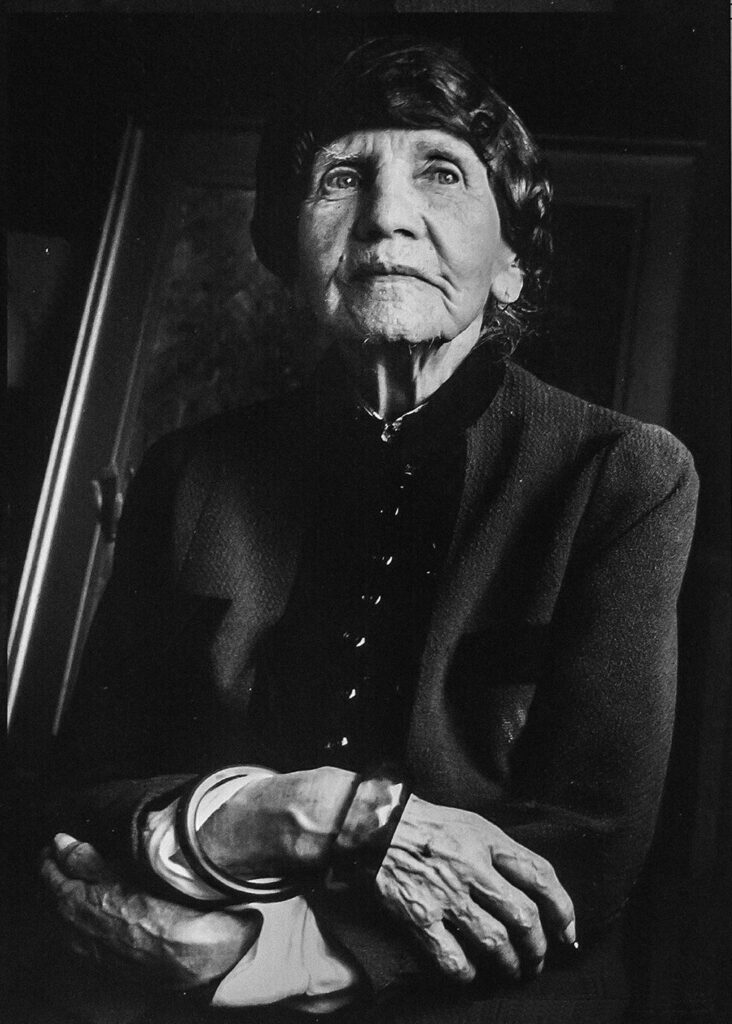

Secondly one could argue that the rhapsodic gush in which her new fangirls and boys shimmer was totally alien to O’Connor’s personal style. She was reserved and ascetic and always sought to be in control of her public and media presentation. The rigour of her control marks the thorough, if understated and un-performative professionalism and discipline that shaped Kathleen O’Connor’s working life. Julie Lewis suggested that Kathleen “rarely admitted to feeling lonely or expressed deeply felt emotions”. Ironically an artist thus becomes the subject of fantastical narratives that appear out of step with what others have read as the tone of her life. However, overly dramatic narratives about artists’ lives are very much part of contemporary popular engagement with art history, and the trend does not show any sign of fading.

Kathleen O’Connor belongs to a very small cadre of Australian women artists for whom one can trace a multigenerational thread of significant biographical and art historical discussion. There are three major publications on her life and career. Whilst one welcomes the fascinating and updated micro-details uncovered during Curtin’s research, and assembled in the text, at the same time when read alongside the two previous publications by Hutchings and Lewis and Gooding, Kathleen O’Connor of Paris substantially stands within their established analytical footprint. Two of these publications are literary non-fiction biographies, the other is a large format artbook published by Craftsman House and Art and Australia. The latter does particular justice to this artist whose paintings have a very material and direct presence. Indeed, O’Connor’s works are amongst the most elusive, yet directly tactile artworks of both the Australian Edwardians and modernists, communicating best through illustration (when not in their direct presence) and resisting textual framing more than those of her peers. O’Connor’s artworks even resonate with current interest amongst artists in the “new materialism”. Although her artworks fall within recognisable genres of Parisian plein air scenes, portraits or still lives, colour and surface are a central concern for O’Connor, overriding the subjects she depicts.

Two Figures, Luxembourg Gardens, The University of Western Australia Art Collection, Photo by Robert Frith, Acorn Photo Agency.

The first biography was begun during her lifetime, when Patrick Hutchings approached her about writing a biography that only was published two decades after her death, and then in conjunction with the comprehensive work of another Perth literary scholar. The most newly published engagement with O’Connor is a hybrid narrative, which does not always work in any of the disciplines it aspires to meet. The author’s story is slightly less engaging than that of her subject, the travel-writing often seems formulaic and does not augment a clearer understanding of the artist’s career and work and the autobiography, the travel writing and novelistic comments also get in the way of any art historical/theoretic discussion. Whilst the bloggers find them congenial, for me the authorial quirks, her nickname ‘Bravegirl’ for Kathleen (why do I think of a Disney Princess?), her conversations and rhetorical questions directed to the artist, intrude into the presence of the artist’s works and the narrative of her career, which should be a key to an art publication.

Yet O’Connor’s appeal appears to be somewhat cross-disciplinary, as her earlier biographer Julie Lewis was, like Curtin, from a literary background. Lewis, Curtin and O’Connor form a de facto transgenerational chain of creative women whose public careers (even Kathleen the expatriate) have been brokered against the terroir of cultural life in Perth.[iv] The ongoing presence of artistic norms and expectations in their community have shaped the careers of both artist and biographers. How has coming from Perth made O’Connor’s working life and her place in public memory different to her contemporaries, Proctor and Preston, for example? O’Connor is a unique figure, at once exhibit A in a regionalist discourse that the art life of the margins (i.e. Western Australia) demands more attention from the centre, yet she was uncomfortable to be identified as Australian, let alone a Western Australian. She saw herself as a citizen of the world, and more often than not self-identified as a British, New Zealand, Irish or even French artist. O’Connor’s documented hostility to critics and reporters referring to her age[v] suggests that she was not happy with exceptionalism and preferred that her artworks be judged on their own merits. Likewise in her own words she cast her engagement with France as the defining element of her career.[vi]

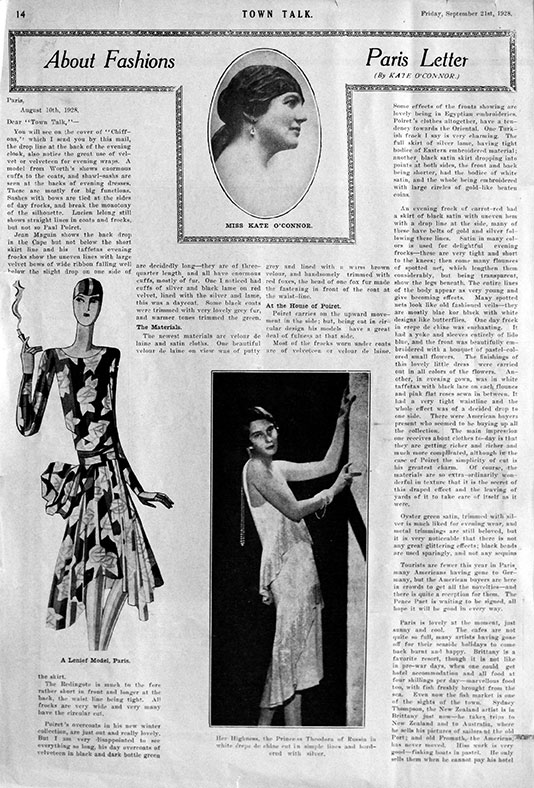

Kate’s column ‘About Fashions Paris Letter’ in Town Talk, 21 September 1928. State Library of Western Australia SRO513.

To give an example of my reservation with the text: When Curtin discusses O’Connor’s visits to Concarneau on the Brittany coast in 1911, we read much about her own present day touristic experiences/impressions of architecture, galleries and shops and little of the fact Kathleen had not ambled into town but had arrived well-prepared with a letter of introduction to an American artist. In turn, he mentioned her and Frances Hodgkins in a letter as cited by Gooding.[vii] These details of professional negotiation and presentation present O’Connor as an agent in control, not a struggling, emotionally susceptible victim. The omission of such precision gives Curtin’s text an air of floating disconnection in which O’Connor exists in a dreamworld-like vacuum, alien to the artist’s actual much-repeated assertion of her professional authority.

The pragmatic and confident O’Connor surely would never have been overawed, as Curtin claims to be, by the formal pomp of historic library reading rooms or the rituals of white glove conservation practices. This stream of consciousness fluffiness, this emotional susceptibility, for me impacts upon the overall merits of the work, despite the range of fresh material that has been gathered and consulted.

Moreover it works against Curtin’s commitment on behalf of establishing O’Connor’s story by sifting through even the most unlikely and trivial of surviving clues, like the Grimms’ Aschenbrödel, tasked to separating the peas from the ashes. Should one bypass the concrete and hardnosed details of a professional life, to concentrate upon a fictionalised narrative of female struggle against denied and lost opportunity?

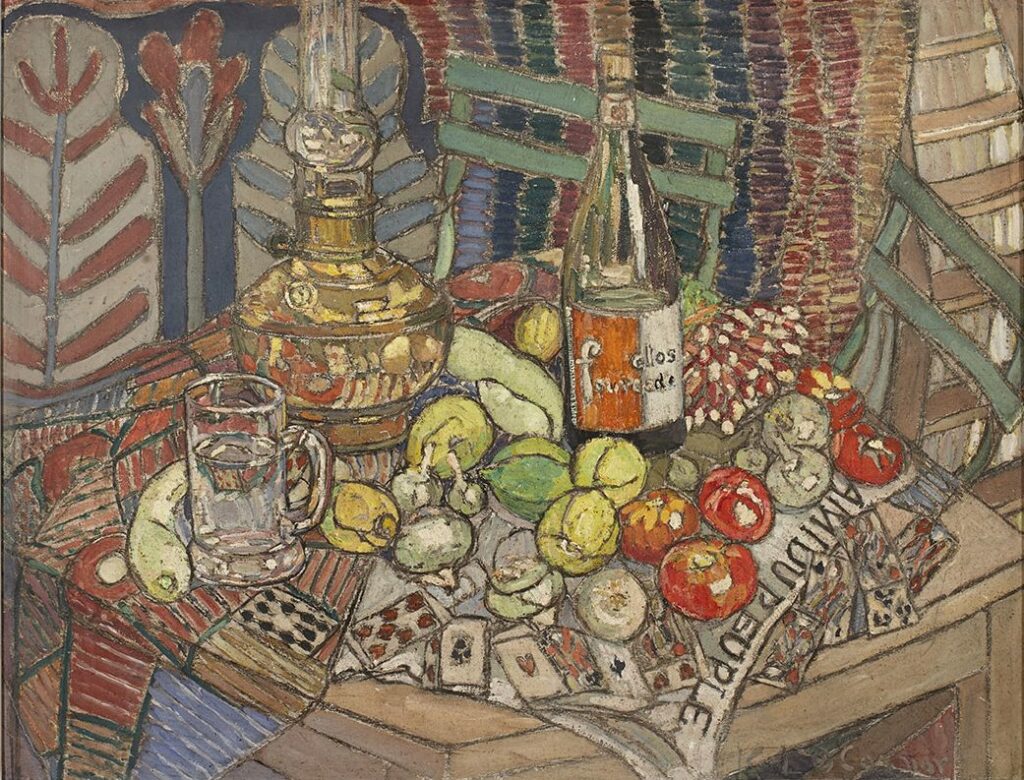

In a Bohemian Atmosphere, 1928, oil. Courtesy of the Shire of Plantagenet Collection.

Likewise the blogosphere’s gratitude at “finding Kate ” offers little acknowledgement that public galleries across Australia over the last five decades since the mid 1960s have been intent on acquiring major examples of her work. There has been a steady curatorial reappraisal of O’Connor over this period, and her works have been part of exhibitions and academic discussions by Mary Eagle, Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson, to name a few. Most notably, she appeared in a PhD thesis by Helen Topliss (ANU 1992), which looked at women and modernism in Australian art. Topliss directly pointed out where O’Connor, Bessie Davidson and others had been left out of major narratives and the error of such omissions. Before submitting her PhD, Topliss had moved from the east coast to work at the Art Gallery of Western Australia and would have had the opportunity to make a hands on exploration of historic artworks produced in West Australia and familiarise herself with a significant art and design[viii] genealogy that, before the internet, was near-invisible to an east coast audience. When in Perth, Topliss collected information on O’Connor by interviewing family members, and Curtin lists these interviews in her endnotes along with those collected by Julie Lewis.

I would suggest if one really intended to “search for” Kathleen O’Connor, as much will be revealed by reading Gooding’s text as reading Curtin’s. Above all the earlier text is set within a network of globally informed scholarship, missing in Curtin’s interpretation, even though far more is currently published and available to Curtin than to Gooding in the 1990s about art making in Paris from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. Slowly, overseas historians and curators are beginning to track and understand the complexities of the cosmopolitan world of art training in Paris from the romantic era to the 1950s, when New York wrested artistic leadership from Paris.

Still Life with Lamp, c. 1920–28, tempura. Courtesy of The Wesfarmers Collection of Australian Art, Perth.

To be fair, Curtin, alongside O’Connor’s previous biographers, has to contend with patchy documentation, and O’Connor’s ambiguous relationship to public acclaim, although O’Connor kept a range of fragments that allow for some details to be assembled, as if she wished for later generations to follow the breadcrumb trail. A consideration of the number and range of sources that survive for women artists as opposed to male brings us back to the question of what documentation can be located to track women artists, and how that archival evidence is then further communicated so that women artists can be viewed in a fresh and effective light. Locating photographic material in the newly digitised Marc Vaux photographic archive, at the Bibliotheque Kandinsky in Paris, is perhaps the most striking and fresh art historical research by Curtin. This discovery places O’Connor not as an outlier but within the norms of artistic Paris, where many artists employed Vaux as a photographer to document their work in the 1920s and 1930s. There are probably photographs of works by other Australian expatriates waiting, as yet undiscussed, in the archive.

In one case, Curtin’s hypothesising crystallises something that eludes the previous biographers, who recognise, but never fully explicate, the contradictions and dualities in O’Connor’s desire for publicity, recognition and rewards, alongside her concurrent scorn of the media and critics and her assertions of her independence and self-sufficiency. Curtin explores the family tragedy that dominated O’Connor’s early womanhood and ponders its impact upon the emerging artist. Clearly the ur-moment, the never-escapable is the suicide of her father, engineer C.Y. O’Connor after being persecuted in public office unfairly on scant grounds, and via what is now termed “fake news”, in the press. His death occurred a century before the current call out and de-platforming culture, and yet is a prefiguring of the intense violence often implicit in such actions. This trauma confirmed O’Connor’s ongoing alienation from and ambiguity about Western Australian society. Additionally, that shattering imbrication of the personal and political set in motion O’Connor’s somewhat stateless, restless future life. The resilience gained from that complete, unforeseen reconfiguring of the certainties of her life perhaps also encouraged O’Connor to accept the transience of life and not to let an opportunity pass, to seize the moment and take the risk. Her art was never a genteel diversion, she committed to the fullest extent she was capable of, and endured the social and political upheavals of Europe in the 1930s to the Cold War era by immersing herself as far as possible in her practice.

Australian Riches, c. 1950; oil and charcoal on canvas, 87.7 x 69.2 cm; Start Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia; gift of the Friends of the Art Gallery, 1963; photograph Bo Wong.

Likewise, Curtin’s family-centric approach vitalises many dispersed sources and small details into print. She fixes the often-fugitive repository of family myth and memory, which remains, when the public record is negligent and dismissive, the key source for knowledge about women artists. In treating family sources with care and attention, the text could operate as a model of feminist art practice and enable other acts of preservation. For that synthesised data alone, Kathleen O’Connor of Paris does earn a place on the professional bookshelf. Furthermore Curtin’s attention to family sources offers a clearer picture of Kathleen’s siblings, adding a new dimension to her life. O’Connor’s sisters were notably more conventional and somewhat different to her. Yet they remained overall supportive of her, and their children in turn fostered bonds to Kate. One of her sisters, Lady Bridget Lee-Steere, had strong first wave feminist interests, supporting the YWCA and the Girl Guide movement in West Australia. Yet my own recent research reveals that her interests extended from social work to women’s art and she was a key early patron of the Western Australian Women’s Society of Fine Arts and Crafts, a group that operated from 1935-2011. Bridget Lee-Steere provided the group with studio space for many years, and was known to that group not only as a benefactress but as the sister of Parisian-based artist, Kathleen O’Connor.

Towards the end of the book, Curtin rightfully outlines the unequal power imbalance that acted against O’Connor in public memory. O’Connor’s west coast origins mean that she is often left out of the larger story. I would also suggest that O’Connor’s gestural, mobile and light-filled surfaces are distinct from the ordered, geometric, design-based modernisms taught to travelling Australians via artists such as Claude Flight and Andre Lhote in British and French art academies. Many of these students returned to Australia and then commenced to teach and exhibit in this style, including George Bell and Grace Crowley. O’Connor’s artworks are not so easily pinned to familiar tropes of Australian modernism and their distinctive quality have made it easier for her to be left out.

Richard Woldendorp’s photograph of Kate aged ninety, 1967. Photograph courtesy of Richard Woldendorp.

In the context of the dominance of the Sydney-Melbourne corridor, Fremantle Press should be congratulated for releasing this latest publication on O’Connor. The story of this de facto east coast bias deserves future discussion in its own right. Meanwhile in the micro focus of a single artist’s career standing out against persistent and dominant stereotypes, both as a decorative expressionist and as an artist whose first professional exhibitions were in Western Australia, Kathleen O’Connor’s story deserves to be told, and if Curtin’s methodology in this latest publication reaches out directly to the public as the online reviews suggest, more people will go looking for O’Connor’s art and asking for it to be brought out from the collection storage rooms of major museums, an excellent outcome. The cultural weighting of commercial publishing being deployed for women artists and for a major “off-grid”, non-canonical figure also demands a degree of celebration, when many narratives of historic women artists are self-published. The realpolitik is that those aspiring to appearing as “cultured” in Australia draw their cues from the output of mainstream publishing houses, and the corollaries to the reach of the publishing house, the “writers’ festivals” across the nation, authors’ media appearances and in-person interviews and “bookchats”. Endorsing and publicising O’Connor’s career via the gravitas and imprimatur of commercial publishing is an important and effective pushback against the myth that “good art” mostly comes out of Melbourne and Sydney. On the other hand, the artist’s own world always surpasses any attempt to tie it down, and is far richer than the attempts to stand between it. If we must have fantasies of old Paris, let them be danced by Leslie Caron and Gene Kelly, sung by Maurice Chevalier, directed by Vincent Minelli and filmed by MGM’s Freed unit. Let the Australian women artists’ stories unfold on their own terms and in their own right.

[i] https://blog.nmwa.org/2017/02/27/challenge-accepted-can-you-name-five-women-artists/

[ii] John Cruthers Book Review: Helen Grey-Smith Aug 1 2017 https://sheila.org.au/blog/book-review-helen-grey-smith/

[iii] Juliette Peers “I am woman hear me weep. Reputations, revivals and the emotional politics of retrospectives” “Exhibitions” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 2000 1:1, pp 213-245

[iv] Conversely Gooding has spent much of her later professional life in public collections outside of Perth.

[v] Curtin p 253

[vi] Janda Gooding Chasing Shadows Sydney, Craftsman House, Art and Australia in association with the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth 1996 p 72

[vii] Gooding Chasing Shadows pp 27-28

[viii] Given that James R Linton’s interest in the arts and crafts movement made Perth an early and nationally significant hub for both the production and duration of design. Concurrently Lewis Harvey did the same for Brisbane. There is a double foldover of conscious overlooking at work, both off-centre, regional and design-based narratives have been sidelined.