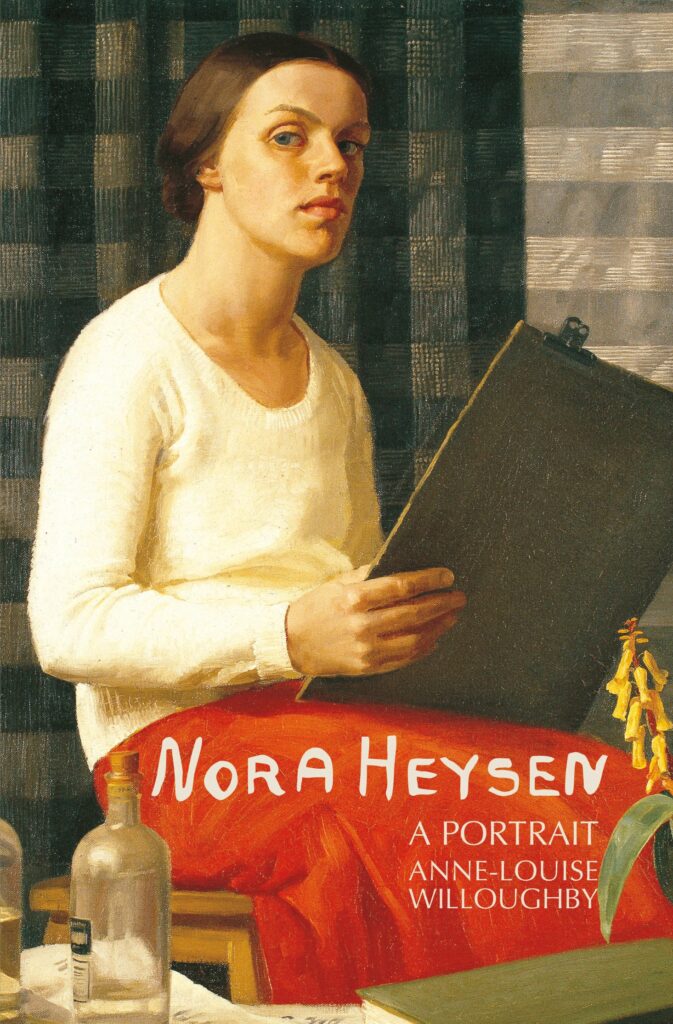

A new biography, Nora Heysen: A Portrait by Anne-Louise Willoughby, and the recent exhibition Hans and Nora Heysen: Two generations of Australian art at the National Gallery of Victoria allow a reconsideration of the life and work of this key Australian artist.

By Juliette Peers

Nora Heyson – A Portrait by Anne-Louise WIlloughby.

Nora Heysen is a singular figure in Australian art. Barely mentioned in standard mid twentieth century overviews, she was a precociously mature talent whose works were acquired by important collections even as a teenager. Such early recognition was a more unusual achievement in the past when younger artists were not deemed to merit special attention as they do today. She easily matches more celebrated youthful “high achievers” of Australian art, Arthur Streeton and Hugh Ramsay. Both her gender and the historical timing of being a realist in the period of emerging modernism have served to erase her from public consciousness. Whilst in later years she specifically spoke out against feminism and was irritated by some of the questions put to her by younger feminist scholars who came to interview her, she was a feminist artist by deed as much as by political conviction. As the first female winner of the Archibald Prize and the first woman sent overseas from Australia as an official war artist[i], she pushed out the low and patronising expectations held for women artists amongst her generation. Her works easily rank amongst the best by any Australian artist, male or female, in the interwar period. For anyone reframing women artists against the wider context of Australian art history, she is a pivotal figure. Nora Heysen’s career demonstrates women artists’ potential impact upon their professional contemporaries, even whilst accepted wisdom and stereotype claimed they were irrelevant.

As an exemplary Neo-classicist and representational artist, she also indicates the poverty of analysing Australian art only through the lens of the development of modernism and contemporary style, or acclaiming only the overturning of supposedly tame convention. For many years Nora Heysen was irrelevant and invisible in either of these widely accepted templates. The technical merits of her art and its surprising emotional charisma (even given its seeming straight forward surface qualities), indicates the limitations of this construct. Some commentators have noted that, like the work of Grace Cossington Smith, Nora Heysen’s works offer content and insights that eclipse the sum of the often everyday items that she chose to depict. Within her paintings and drawings the attentive and attuned may read both a candid self-revelation – her flower pieces often reflect her mood and circumstances – and a spiritual dimension. She spoke of following Cezanne in seeking the underlying permanence and structure behind the fleeting presence of flowers and nature. Her two periods of painting in New Guinea, despite often involving physical hardship, reveal a latent and volatile romantic element of her vision, as she responds to the people, culture and landscape of that country, that was so different to her Australian base.

Most importantly, Nora’s values and attitudes, as recorded in her firsthand statements and interviews, are shared with myriads of Australian artists both past and current. Such values include a close focus on the act of “painting”, to the exclusion of social or political matters, a commitment to capturing both form and light and also a high degree of competence in handling materials. A key element of Nora’s singularity is that material achievement and emotional and intellectual energy in her work directly match. Alas all too often many currently active painters, who concentrate on literal representation, fall short of both the technical precision of drawn form and the psychological and cultural nuance seen in Nora Heysen’s best works. Yet we ought not forget that many artists have been, like Nora Heysen, locked out of key models for defining creativity in Australia. Many working artists are neither validated through public gallery acquisition nor by public funding, due to their chosen style or their approach to artmaking. Too often it is assumed that obscure artists beyond the public canon (in many cases women) are dull and repetitive. Equally it is believed that key texts capture all the artists that professionals and collectors need to know, an assumption that is clearly inaccurate, as the case study of Nora Heysen so strongly documents.

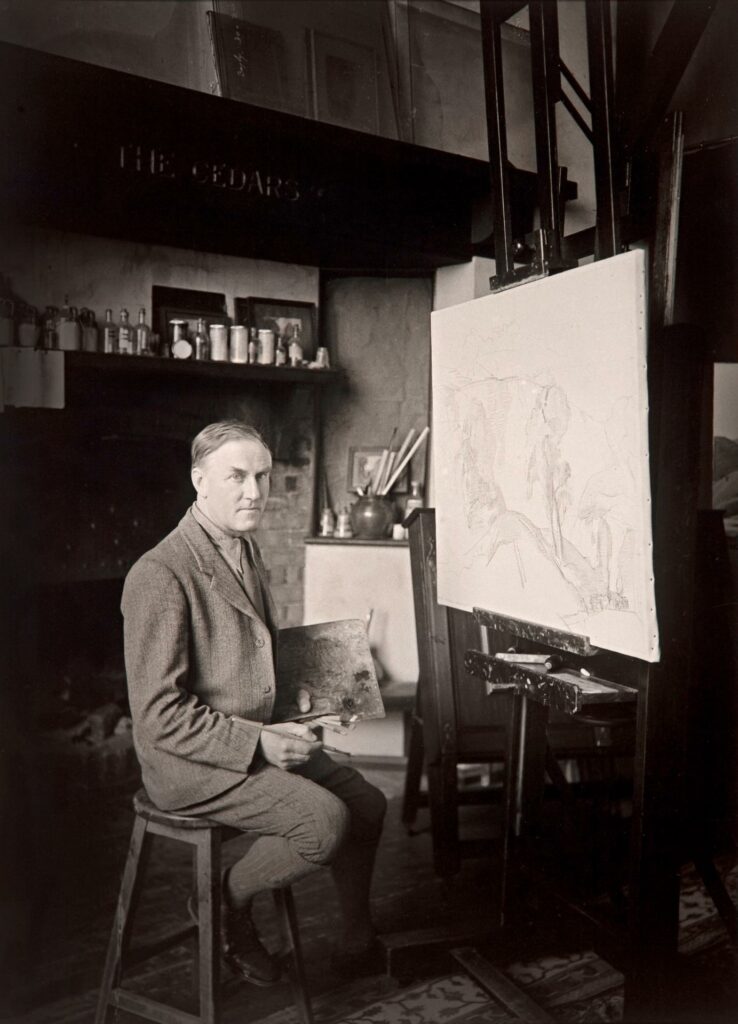

Lest we place Nora Heysen in a simplistic binary against radical art, she disrupts conservative myths too. Her gender was a primary dissonance to cherished belief. It was taken for granted that a towering kinglike figure like Hans Heysen would have an “heir”, but that the successor would be a female child was unexpected. The dynamics of the relationship between father and daughter artist, well documented in Cathy Speck’s collected edition of their correspondence[ii], adds an unexpected dimension to both Heysens’ careers. Their letters across many decades offer a candid insight into the working life of both artists and their shared focus upon the craft of painting. Nora’s emergence from the cultivated, sophisticated milieu carefully managed by Hans and Sallie Heysen at their country home, The Cedars, renders Hans Heysen’s career and impact more interesting and unexpected than the subjects of his paintings would suggest. The inclusion of objects, painted by both Hans and Nora Heysen, in the shared retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria documented the visually rich world created by two generations of Heysen artists, together with Heysen’s formidable wife Sallie. This exploration of the sophisticated and urbane homelife shared by the Heysens suggested that Australian artists, stereoptypically regarded via factoids as conservative, were actually culturally literate and intelligent, a concept has been assumed to be a contradiction in terms since the Whitlam era. Likewise the loud streaming of Mozart music within the section of the exhibition devoted to flowerpieces reminded the viewer that the Heysen family never held a xenophobic and arid cultural vision[iii], but viewed themselves as part of a greater continuum of creative life. Nora Heysen loved baroque and classical music and particularly chose recordings of Mozart whilst she worked in her studio.

Nora Heysen, Gladioli 1933, oil on canvas, 61.5 x 47cm, The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia, copyright Lou Klepac.

In view of the tenacious hold of patrician traditions upon cultural broking in Australia, Nora Heysen is the most fully rounded and independent of the legions of painting children and grandchildren of iconic Australian artists, such as the younger Boyds, Percevals, Harts and from an earlier era the younger Lindsays, Withers and McCubbins. Only perhaps in more recent times has another child of iconic artists, Larissa Hjorth (daughter of John Olsen and Noela Hjorth) established a creative persona that, like Nora Heysen’s, robustly stands independent of familial legend and lustre. Conversely Rebecca Martens has been consistently belittled against the work of her father, who actually shares a number of the “faults” laid solely at her doorstep.

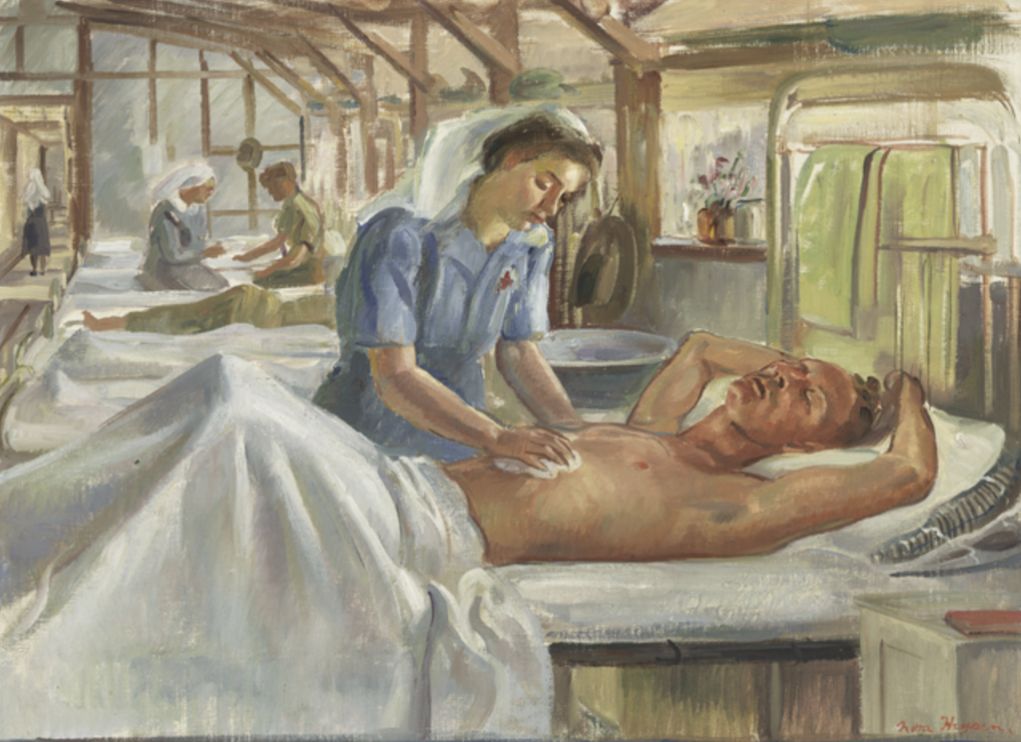

Nora’s breadth and independence of mind also surprises. As an official war artist, she chafed under the formality and red tape of military regulations. In her correspondence with Major Treloar, she rigorously defended her choices and even rights as a creative professional, against a degree of sexism and a fairly limited vision of the nature and function of art, as basically illustration. Treloar was the godfather, literally and figuratively, of the Australian War Memorial. Whilst he emphasised the documentary aspect of the collecting and foregrounded the military experience of the Australian soldier, he also created a remarkable proto-post-modern conceptual base to the institution, building an immersive, often intimately personal material culture via the objects of the collection. Whilst irritated by Nora’s contesting his opinion and directives, at the same time, if never conceding defeat, he moved relatively slowly to chide and restrict (despite on-paper bluster), giving her a de facto space to continue with her work. Nora also put up a spirited defence of her actions in letters back to Treloar on the grounds of her professional experience and the needs of her practice. A long thread of feminist scholarship around Nora’s military commissions by Anne Gray, Cathy Speck and Lola Wilkins has been crucial to the rehabilitation of her reputation in public culture. Gray identified the significance of both Nora Heysen and Hilda Rix Nicholas over thirty years ago via the Australian War Memorial holdings and was perhaps the first person to unequivocally endorse both artists.

Nora Heysen, Sponging a malaria patient 1945, oil on canvas on plywood, Australian War Memorial, ART24273.

Nora defied her parents and convention to pursue a relationship with a married man during World War II. She then lived with him for nearly a decade before she ultimately married him. Later she maintained friendships, partly via her god daughter, with a number of notable figures who held strongly divergent political views to her own, such as Dorothy Hewitt and Merv Lilley. The latter’s vividly characterised portrait was included in the recent NGV exhibition. Nora kept her strong, mostly conservative views to herself, but neither expected her friends to share her opinions, nor “dumped” or unfriended anyone who had different beliefs, as is totally endorsed and acceptable today. A person whose company she enjoyed was a greater entity than their values or their politics.

Her most enduring relationship of her later years was non-conventional and distinctly forward-looking: her friendship with Steven Coorey, an adolescent boy coming out. Nora provided a locus of belonging and confession, and he moved into her home in Hunters Hill. He shared her love of flowers, gardening, cats, antiques and art, and these mutual interests provided the foundation for an enduring, yet flexible bond. After Steven moved to San Francisco they corresponded regularly around such themes, vividly bringing their immediate experiences to life for the absent friend. This friendship extended to the young man’s partner, who later became a live-in carer for Nora. On the other hand, Sallie Heysen was disquieted by non-standard relationships. Her open hostility to Nora’s close friendship with sculptor Everton (Eve) Stokes was fuelled by fears of same sex relationships and ensuing damage to the Heysen family’s reputation, as well as by Eve’s lower social class in Adelaide. Equally Sallie believed that Eve was an exploiter, parasiting off the Heysen “brand” (as would be said today) and prosperity as well as Nora’s creative energy. Nora persisted with the friendship, despite her mother’s complaints, much as she would stealthily outplay Treloar later.

Appropriate for Nora’s singularity, the first full biographical study of her is also a standout. Rarely can biographies of Australian artists be reviewed with as few qualms and complaints as can Anne-Louise Willoughby’s recent biography of Nora Heysen. Life narratives of Australian women artists in particular are blighted by an emotional over-dramatic tone of writing, often interposing the writer over the subject of the biography. There is a trope of the writer linking his or her – current and all too often trivial and trite – difficulties, feelings and experience to those of the historic subject, as if the writer was of equal importance and as skilled as the artist under discussion. Editors and publishers clearly think this type of superficial writing is either innovative or lucrative. There is often in Australian reviewing and writing practice a gushing sycophantic laxness which assumes that the production of an eminent, high ranking writer is automatically flawless, when often it is far from such a standard. In this case of Willoughby’s biography any plaudits are justly earned.

Image left: Nora Heysen, Self Portrait 1939, oil on canvas on board, Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art.

Image right: Harold Cazneaux, Nora Heysen 1939, gelatin silver photograph, Art Gallery of South Australia.

Willoughby’s wide-ranging, intelligent narrative directly captures the reader’s attention. Nora’s career unfolds against a social and political background that is confidently mapped and up-to date in its sources. These “sidebars” in turn enrich and extend the reader’s ability to engage with Nora and emphasise her cultural significance. Similarly a well-informed but never over-dominant infilling of the backstories of the diverse persons whom Nora encountered during her working life again builds upon current scholarship and underpins her rightful presence in Australian public memory from the 1920s to the twenty first century. All this is achieved without too great a recourse to the tired clichés often deployed when writing about historic Australian artists. The biography covers more thematic territory than many similar life narratives of Australian women artists, partly due to Willoughby’s skill, but ultimately drawn from Nora Heysen’s multilayered, acutely-felt experience of the world.

Possibly the biography gains by being written by an academic with a more general humanities background than an art history specialisation, as the need for particularly student and young historians and curators to primarily address their peer community often diverts them from tracking parallel fields of scholarship (other than in the most routine and expected manner) that lie outside discourses that serve career-path needs. Nora Heysen: A Portrait resembles the strong tradition of North American and British literary non-fiction rather than the Australian humanities sector’s longstanding (since the 1950s) habit of emphasising political tendentiousness at the expense of [perhaps humble] narrative and content and even the subject under discussion. Equally it does not fall into the trap of attempting (and embarrassingly failing at) a lite version of l’ecritrue feminin, with rambling authorial musings and catharsis, which is usually offered as an alternative to academic formality when discussing Australian women artists. Curiously the unexpected complexity offered by Nora Heysen’s works themselves is again brought to mind by the nature of the text itself, a tranquil, ordered surface masking an astute, multilayered inner self. Intentionally or unintentionally the biography appears to be profoundly shaped by the aesthetic of its subject, as indeed a biography should be, but so rarely is.

By moving into unexpected territory the biography stands as especially impressive within the canon of Australian feminist art history. In particular Sallie Heysen emerges as a significant and influential figure. She was single-mindedly determined to build and support her husband’s fame. A daughter who had made a socially unacceptable marriage was forced by Sallie into interstate exile and penury. Nora and others in the family believed this banishment led to Josephine Heysen’s premature death in 1938 (although her surviving letters are upbeat and positive in the months before her death). Sallie felt obliged to send her daughter away, lest the elaborate networks of social patronage that she had built up around Hans Heysen’s art were jeopardised by a social faux pas. The stakes were even higher because Sallie had given up her own art career upon getting married. Sallie stands as equal to other significant manager-wives who supported and enabled iconic Australian artists, including Cynthia Reed Nolan, Minka Veal, Annie McCubbin and Fanny Withers. Again the sense of “knowing” Hans Heysen’s art shifts significantly when it is understood that the buoyancy of his career was substantially dependent upon the skills, energy and finesse of a woman. Nora observed Sallie’s techniques for encouraging the wealthy and well connected to buy and commission, often by hosting convivial social events, well supplied with food and drinks, and in turn used her mother’s strategies to sell her own art.

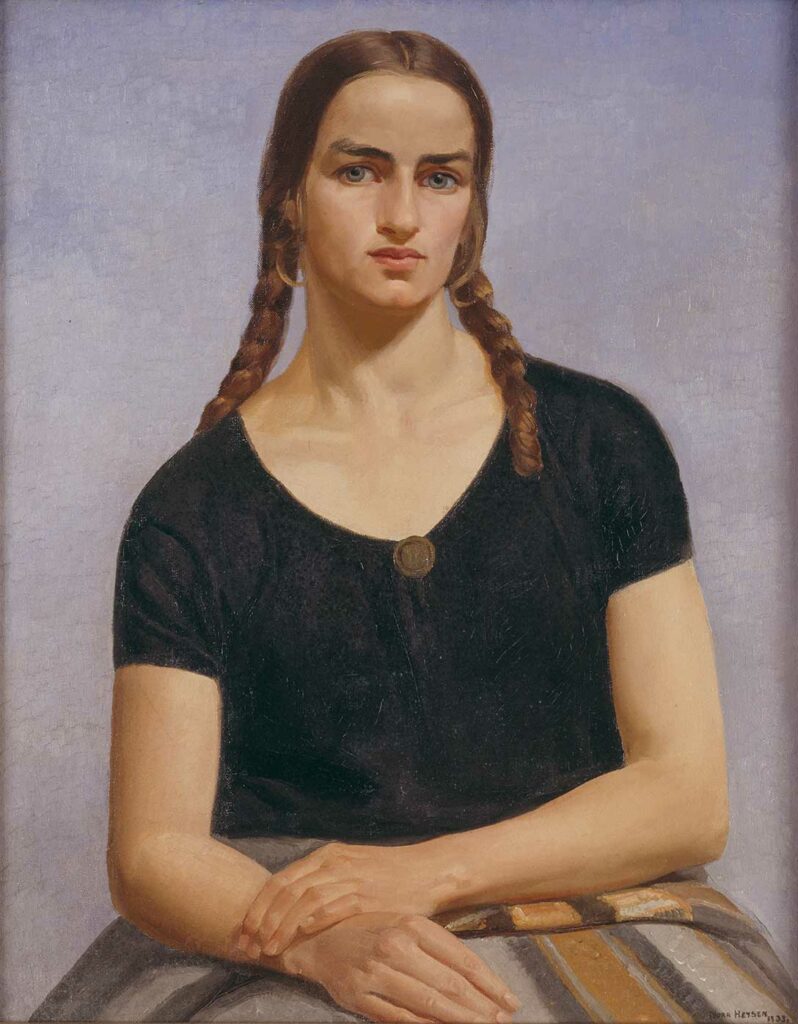

Nora Heysen, Ruth With A Blue Background 1933, oil on canvas, 75 x 59cm, The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia, copyright Lou Klepac.

Sallie also firmly “managed” Nora’s career in ways that she considered were beneficial to Hans Heysen’s professional life. She organised a new studio to be built for Nora, so she did not disrupt her father in their shared studio. Likewise Sallie located a local agricultural worker to be a model for Nora, thus making sure there were not two Heysen landscapists to confuse the public. This sitter, Rhonda Paech, was renamed Ruth by Nora. In a series of outstanding figurative studies. Nora presented “Ruth” as an individual and real presence, yet equally a powerful archetype that like the work of the plein air school and her father’s oeuvre, also could be understood as seeking to exemplify something of the settler Australian character and experience. The same compelling scrutiny of character and control of design and drawing can be seen in a series of self portraits by Nora, that commenced around the time of the “Ruth” pictures. They share the same clarity of touch and psychological acuity. Nora turned to self portraiture not as any statement of self ambition or vanity, but because she as a subject was always to hand, could be scrutinised at length, yet did not need any elaborate managing of appointments and negotiations over price and payment, as for example an Archibald entry entailed.

In response to her mother, Nora grew to be apparently docile, conformist and somewhat otherworldly, yet this persona disguised a determination to make her own choices whilst quietly avoiding conforming to uncongenial strictures and social conventions. Willoughby pinpoints the effect of familial experience upon the development of Nora’s career, and the complex duality by which Nora kept true to a family ethos that she respected, even revered, yet also resisted by moving out of South Australia and entering a relationship that was hardly any more palatable to her mother (in particular) than was that of her elder sister. Yet Nora also managed to reconcile her family to the situation, until they offered grudging congratulations on her much belated wedding. It was generally believed amongst Nora’s family and friends that Dr Robert Black’s first wife delayed agreeing to a divorce until it was too late for Nora to have children.

Such charting of the dynamics of female lives, choices and social mores in early and mid-twentieth century Australia offer an unusually clear picture of the interaction of female experience of the recent past with professional artmaking from the 1930s to the 1980s. The trajectory of Nora Heysen’s career as set out by Willoughby informs considerations of the uncomfortable mechanics governing women artists’ fates in mainstream Australian art, particularly the complex and elusive processes that assigned them rank in the artworld. Equally Nora’s career offers grounds for why this situation has remained substantially unchallenged by Australian professionals. Celebrating women as modernists often plays out in effect as a curatorial version of low church Christian “headship”: women are simultaneously cherished, yet sidelined as separate and different to men, rather than belonging within the centre of discussion that leads from von Guerard to Ben Quilty. Of course the material cultural evidence points to the efflorescence of a strong generation of women artists in the interwar period who were invisible for two to three decades until the 1970s and second wave feminism. I am not attempting to erase this notably strong generation of artists nor question the long thread of feminist academic and curatorial scholarship directed to the modernist generation, but an uncritically enthusiastic celebration of interwar modernist women does not destroy the “Master’s House”, with or without his tools. Rarely are the multiple pressures that were brought to bear on women artists analysed in such detail and precision by Australian scholars as in Nora Heysen: A Portrait. Whilst nominally there is much discussion around such issues, published arguments often descend into generalisations and clichés that haunt both professional writing and certainly many postgraduate theses, possibly because secondary accounts tend to feed off an accepted but narrow range of sources.

The biography moves beyond tired myths and follows a woman artist’s experience from the relatively buoyant interwar period to the disappearance of women artists after World War II. Whist we may associate discussions of female sexuality and its impact on creative life with – say – the writing of Janine Burke on Joy Hester, Nora Heysen drew nude studies of her new lover asleep at night. Her choice of subject was both highly charged in the context of her life story and, to a great degree, without peers in the known oeuvre of other female artists in Australia at the time, except perhaps in the more avant garde oeuvre of Joy Hester or in Mirka Mora’s drawings from the 1950s onwards – although one should note that this particular comparison is only partial as Mirka’s drawings are evasive, more fanciful and less autobiographical than Nora’s. Mirka renders the lovers as hybrid half animals and half birds and withholds the subjects’ actual identities. Nora successfully inhabits a territory more famously associated with artists who have been cast in public memory as rebels. The letters exchanged by Nora and Robert Black, as quoted by Willoughby, indicate the depth of the mutual attraction between the two and evoke an unexpectedly hedonistic world rather than that of a Douglas Sirk film or a Graham Greene novel, where mid-twentieth century adulterers suffer much anguish and are narratively punished for their moral transgressions.

Nora Heysen, Pathologist titrating sera (Captain Robert Black) 1944, oil on hardboard, Australian War Memorial, ART22409.

In her drawing of the sleeping Robert Black Nora Heysen also inverts the usual gender hierarchy of modernism – as exemplified for example in Picasso’s Vollard suite (and throughout much of his later oeuvre), where the female is the subject of the male genius’s contemplation and frankly cast as the passive object of his desire. Yet sadly Nora’s unconventional relationship unravelled her art career as relentlessly as would a standard respectable post-war marriage. For example Black’s sudden return to Australia from England made Nora also cut short her stay in the productive climate of a volatile and changing post war Europe. Her career may have been significantly different if she had stayed for the extended period that she planned. Willoughby delicately infers through the recollections of Nora’s friends and family, and even Robert Black’s somewhat estranged son from the first marriage, that Black was self-absorbed and expected the household to revolve around his comfort and interests. His great obsession was amateur radio, and he spent his evenings in a constant aurally disruptive yet trivial chatter with other radio enthusiasts. Moreover his bulky shortwave radio sets and equipment progressively ate up Nora’s studio space. Black was a medical researcher and academic with a notable career and he seemed to have been a less iconic version of those towering male academics who dominated and governed post-war Australian cultural life, Manning Clarke, Bernard Smith, Panzee Wright etc, as well as their advocate Nugget Coombs. Whilst all may have derided Menzies’ enveloping power over post-war Australia, these post-war giants acted as if they naturally deserved the same total autocratic status.

In the long term the relationship did not favour Nora’s career and it comes as no surprise to the reader that Black finally left Nora for a nurse who worked on his medical team. Nora was deeply hurt by her betrayal at the hands of the man to whom she had devoted so much energy, as an expression of her own devotion. She then displayed real emotional courage and generosity of spirit in setting out on her own, later in life. Away from the mainstream world, Nora created an enclosed but productive haven, vividly outlined by Willoughby. Her bountiful, large garden, which she tended, provided many blooms for her still lives. At one stage there were 32 cats in her household; faced with an increase in her house guests and furry family, she just went out and bought more cat food. A remarkable large painting Morning sun 1965, included in the National Gallery of Victoria survey, showed a number of Nora’s white cats sunning themselves on the back porch and vividly conveyed the enchantment of the world Nora had created for herself.

The material culture and rhythms of this world not only live tangibly for the reader through Willoughby’s prose, but again raise questions about what and who are considered important in cultural memory and cultural celebration. When the NSW Society of Artists closed down in 1965, Nora had few outlets to exhibit, so she became even more obscure. Curiously Nora Heysen’s later years were somewhat parallel to those of Sybil Craig in Melbourne, who had been the third woman artist commissioned as an official war artist during World War II. Sybil too lived and worked isolated from the broader artworld, surrounded by her treasures in a house that had hardly changed for decades. Certainly there was something remarkable about both women’s persistence and their deep commitment to working without much acclaim or support from the larger professional artworld of the day. Moreover visitors were often drawn to the distinctive enclosed, utopian world each woman had created by her own willpower. At the same time it is hard to think of similarly talented creative men in Australia who were left to languish in such a half life. There is a point where artworld professionals should be held culpable for their lack of either a flexible vision or empathy to those beyond peer group esteem.

Willoughby also unpicks the specific politics of how Heysen was “rehabilitated” by the actions of a series of influential curators including Hendrik Kolenberg and Barry Pearce. Such dynamics are often taken for granted in other accounts. However again the question could be raised as to why women artists of Nora Heysen’s generation often have had to rely upon the intervention of a curator or a dealer to bring the work to public attention. Why does the mechanics of culture place such a reliance upon the influencer or the interlocutor when the works themselves are of intrinsic merit? Again it is the reliance upon the expert rather than the artist herself that is an issue. If as the Guerrilla Girls say that seeing your career pick up at 80 is a privilege of being a woman artist, then why does the work, which surely does not change, remain invisible until endorsed by a third party? How has the curatorial validation grown to speak more eloquently than the work itself, and why are people reluctant to engage with works that have been bypassed by “experts”? Or does the action of bypassing an artwork also suggest limitations to the “expert’s” judgement, as much as faults in the artwork? Given that institutions often see themselves as the vanguard of social and cultural change, those within the institution then appoint themselves as the drivers of that change, claim that space and endlessly self congratulate, being well tutored by Bernard Smith in that regard of self-applause. Calls to diversify or decolonise the canon or the curriculum – in terms of gender, ethnicity, ability, wellness, class – often equally confirm the authority of those who manage the process as much as the qualities of the works uncovered. Equally particular figures and artworks are themselves institutionalised and privileged as the face and proof of cultural change.

Whilst Rex Butler in his recent in-depth review of the father and daughter Heysen exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria [iv] suggests that Nora’s attempt to assimilate modernist techniques in London in the mid 1930s, and her work as a war artist, distorted the exquisite balance and intuitive sensibilities of her art, this charge of losing an inherent integrity whilst chasing the chimera of fashionable modernisms could I think be more fairly made against Constance Stokes. In Stokes, Australia lost another rigorous interwar Neo-classicist and gained a more routine middle ranking modernist whose artworks never quite matched either the intensity of her commitment and knowledge, or her acclaim amongst Menzies’ era cognoscenti, not withstanding that Girl in the red tights was highly esteemed including by British critics and was even shown in the Venice Biennale.[v] Nora Heysen is far better served by Willoughby than Constance Stokes by the partisan and ego-driven tale of The lost mother by Anne Summers[vi] that doubles as a biography of Stokes. This latter narrative is undercut by the usual intrusive authorial musings and also by seeming to fail to understand that the drop off of quality of Stokes’ art led to the gradual diminishing of the high reputation that was promised at the start of her career.

Harold Cazneaux, Portrait of Nora Heysen at work, 9th March, 1939 1939, gelatin silver photograph, 18.5 x 14.2 cm, National Library of Australia (PIC 3692/3).

Rather than Nora disintegrating, when viewing the National Gallery of Victoria show Hans and Nora Heysen: Two generations of Australian art, as suggested by Butler, I felt that Hans grew more stale in plain sight, even though I certainly enjoyed seeing his works. As one walked through the exhibition he became increasingly formulaic and a prisoner of his own aspirations, or perhaps the expectations and uses of his art, that seemed to weave an increasingly hyperbolic and uncritical web around the artist – although possibly this was a result of the selection of works. The earlier works show an artist of technical bravura, exploring a wide range of subjects and creative tests. Ironically the final room of Central Australian landscapes by Hans reified the white Australian possession of the land, by the sheer volume of studies and also its celebratory position as the valedictory gesture to the whole installation, even as it supposedly sought to displace the traditional colonial vision of Australian landscape painting.

Harold Cazneaux, Hans Heysen in his studio 1935, gelatin silver photograph, 25.9 x 19.0 cm (image & sheet), Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Gift of the Cazneaux Family 1978 (7813Ph87).

Hans Heysen’s homemade caravan sat in the centre of the room like a pilgrimage shrine or the Dome of The Rock, its pointed roof being appropriately ecclesiastical, encouraging thoughts of reverence in the presence of holy relics. I tended to read Hans in terms of the dullness and expectedness of mainstream Australian cultural broking, his institutional predictability imbricated in the process by which the curatorial industry that once belittled him now again lauds him. As one moved through the exhibition, Hans Heysen increasingly became a self fulfilling prophet, an especially apt sign for the often enclosed loop of Australian culture. Nora’s works were fresh and unfamiliar, and the room full of her wartime work was – in terms of placing women against large scale popular myths of white Australia – genuinely exciting. Her drawings were as strong and fully rounded as Nora herself suggested they were. She argued in this manner to Treloar, when he was complaining about how few oil paintings she had produced in relation to too many sketches. Her artworks were genuinely informative about aspects of female participation in World War II, too often omitted from standard accounts. With the strong popular interest in military history, these works would have spoken to many outside the artworld, rightfully drawing new attention to her. The wartime commissions also revealed Nora as a highly focused and confident artistic agent.

I certainly agreed with Butler that the father daughter project was more informative, more impressive and less tokenistic than recent National Gallery of Victoria offerings around women artists. This exhibition highlighted the phoned-in nature of their recent shows about women. Such shows include the small private collection loan exhibition of domestic scale works – which confirmed the graceful, sweet outsider status assigned to many women artists – and the unenterprising recap of The Field exhibition. The latter exhibition struck many gallery visitors as less exciting and less historically impressive than the hyperbolic publicity drive claimed, and the historical and intellectual justification to the show was somewhat self-seeking and flimsy, given that the exhibition’s lustre had faded amongst more recent generations, who are interested in revolutions other than colour field abstraction. The show was pitched at a strange place somewhere between the intellectual gravitas of Clement Greenberg and the funky retro populism of the Austin Powers franchise.

Whilst there has been four decades of documenting, counting, exhibiting, debating and celebrating Australian women artists, much of this activity has seemingly brokered no lasting change, in particular to norms and structures around art history and the canon of artists who are admired, collected and researched. The newly released The Countess Report 2019 documents many positive changes but confirms that Australian state institutions particularly have remained imbalanced in both acquisition and display in favour of male artists.[vii] The issue is exacerbated as public galleries are undoubtedly the peak influencers via their large collections and the intellectual weighting of their publications. Additionally their status as popular tourist destinations extends their influence far beyond art professionals. Recent studies from the United States also confirm the overwhelming male bias in the collecting, exhibiting and research of women artists, especially at the academic and institutional level. Statistics reveal how little impact recent agitation on behalf of women and minorities has made on the canon as understood in North American art museums. The lack of research brokers lack of validation and the low status of women’s work. [viii] The fundamental conservatism (despite proclamations to the contrary) and enclosed loop of academic bodies also reinforces the slow response and the self-affirming nature of the canon.

In the context of this artworld stasis, these two recent engagements with Nora Heysen – Willoughby’s biography and the Hans and Nora Heysen exhibition – have shifted the norms and probed beneath the expected clichés of the surface to examine the underlying drivers of how women’s careers played out in the Australian artworld of the relatively recent past. Such incisive and fresh revisions suggest that when projects move beyond the expected and familiar paradigms they broker movement and change. Outflanking the known and acceptable takes us back to the long term ambitions of Sheila Foundation. The long history of cyclical disappearance and reappearance of women’s art within the public and commercial gallery exhibition programs, and the great generalist fascination with women’s art that contradicts the documented institutional hesitance makes us consider what are to be the fabled “next” steps in feminist art appreciation? If large scale institutional plate shifts in order, yet how can that happen when institutions rigorously guard their own status as peak leaders and change makers?

[i] Stella Bowen, also commissioned, had been living and working outside Australia for many years

[ii] Heysen to Heysen: Selected letters of Hans Heysen and Nora Heysen, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2019

[iii] No matter how Hans Heysen’s art has been used. In an era when statues are often torn down for their symbolism, we should stop viewing art through the simplistic interpretation where an artefact equals the ideologies of those who make use of it, whereas an artwork may have multiple meanings and contexts. Heysen’s works appeal outside the political uses made of them.

[iv] https://memoreview.net/blog/hans-and-nora-heysen-two-generations-of-australian-art-the-ian-potter-centre-ngv-australia-by-rex-butler

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girl_in_Red_Tights

[vi] The lost mother: A story of love and art, by Anne Summers, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2009

[vii] https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/the-art-show/countess-report-released/11651230 This interview with Amy Prcevich explicitly discusses some of the uncovered data in The Countess Report 2019 around gender imbalance at larger institutions.

[viii] https://news.artnet.com/womens-place-in-the-art-world/womens-place-art-world-museums-1654714?fbclid=IwAR3kzE3RNlWFkRGh5twS0AfZpc2V-6Av405REqKTwQb4NR1psBgMgSYC3E#.XalXxRTgDXk.facebook