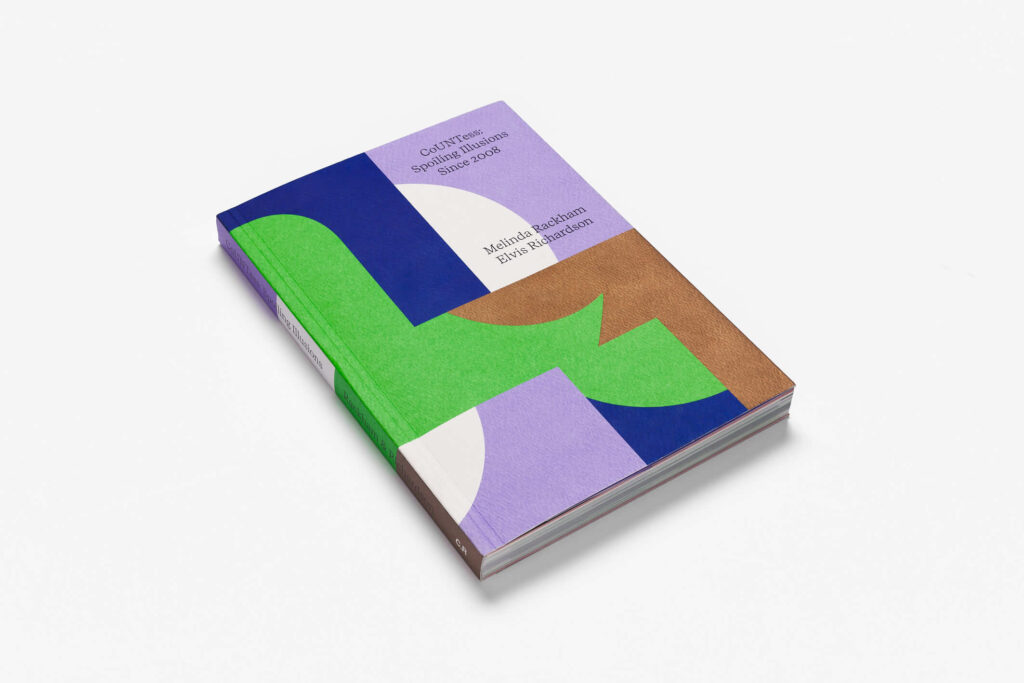

Louise Mayhew reviews a new book by Melinda Rackham and Elvis Richardson that tells the story of CoUNTess, how it morphed into The Countess Report and how it continues to challenge gender bias in the Australian artworld.

Melinda Rackham and Elvis Richardson, CoUNTess: Spoiling Illusions since 2008. Countess.Report, Melbourne, 2022

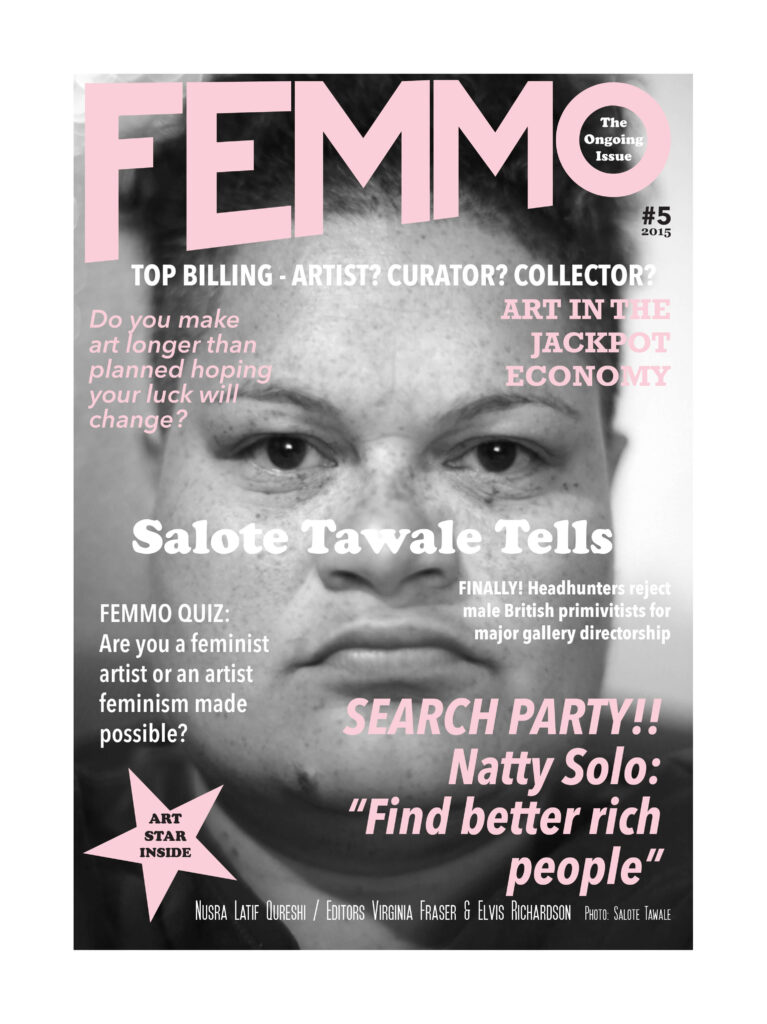

A museum system that values and collects male artists over female; the academies that employ and promote male educators over female for no reason other than their gender; publicly funded magazines that promote male artists on the cover and in the majority of articles; exhibitions and prizes that seem equitable on the surface, but consistently provide more immediate resources and long-term exposure to male artists.

These dynamics of power are not exceptions—they are the rule—and they are riddled throughout every aspect of our culture.[1]

For over a decade, the CoUNTess has persistently counted. Her pie chart- and bar graph-filled blog posts tallied the galling, widespread and undeniable inequities of Australia’s artworld since 2008. Further countesses and funding made possible the CoUNTess. Reports (2014 and 2018) shifting the ad hoc counting of the original blog into Australia-wide benchmarking snapshots of unbalanced gender ratios across the sector.

In CoUNTess: Spoiling Illusions since 2008, Elvis Richardson, the cardinal CoUNTess, and lifelong artworld colleague Melinda Rackham draw on and draw out this data. Equipped with evidence, both statistical and embodied, of the artworld’s deeply-entrenched gender biases, they speak with compelling authority, reiteratively proving their findings, summarised in the excerpt above, that gender bias features everywhere we might look, sometimes blatantly and sometimes more insidiously, but it is always, undeniably, there.

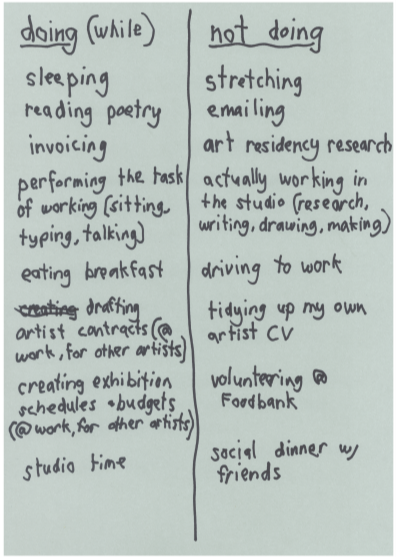

Amy Prcevich, Doing (while)/not doing 2020, ink on paper 59 x 42 cm

The book loosely follows an artist’s career, with chapters dedicated to high school art education, art school statistics, exhibiting careers and artworld prizes as well as attending to the phenomenon of women-only exhibitions and initiatives. Within this chronology, original CoUNTess blog posts appear, reminding us of Richardson’s wickedly witty and clever tone and the very effective picture she created of the CoUNTesses as anonymous, omnipresent, resourceful and merciless counters, holding the art world to account.

With the extended word count of a book, the CoUNTess project refines its voice/s. Here the cheeky candour and intrigue of Richardson’s early blog posts are fleshed out with a new rigour and confidence. This new tone is equally scholarly: drawing on extraordinary swathes of feminist research; personal: positioning CoUNTess data in parallel with Richardson’s own biography; and transparent: providing behind-the-scenes insights into the CoUNTess project, including poignant and missed invitations, such as when Richardson—as the CoUNTess—was invited to launch Finkelstein Gallery, but not—as an artist—to be part of its stable. In turn, Spoiling Illusions offers a mistress-class in feminist writing.

Artists for Workers (Miranda Samuels) New Museum Same Old Bullshit 2020 Digital prints various dimensions Photo: Artists for Workers

In Rackham and Richardson’s own words, Spoiling Illusions is also polyvocal. It eschews the masculine paradigms of a single voice or linear narrative in favour of sprawling and tangential references. It is partial, asynchronous, collaborative and collective. It foregrounds the authors’ co-writing process; shares named and anonymous comments on the CoUNTess blog; and warmly acknowledges expert assistance, contributors and funders, as well as the women artists, writers and researchers they celebrate and on whose shoulders they stand. In the opening pages of Spoiling Illusions, this style rubs against academic expectations but as I settled into the pace and pattern of the text, I found the authors’ roaming insights—from statistics on youth suicide to AI gendered and racial recognition and how many people know bus drivers—fascinating. Moreover, Rackham and Richardson draw into their text a staggering number of key feminist ideas and initiatives from the past decade, providing an exceptional introductory text for emerging researchers.

Turning to the text’s message, in addition to the bold reality of gender bias that is easily surmised by looking around an art school classroom and then walking into a public gallery, perusing a list of commercially represented artists or flipping through the pages of an arts publication, Rackham and Richardson make clear that deeper analysis, only possible with the collaboration of institutions, reveals even more dire, and often compounding, inequity. For example, female/male recipients of a prestigious early career scholarship program appear relatively balanced (ranging from 50 to 55.6% female recipients over 1992 to 2019), however applicant records indicate women are more likely to apply (ranging from 60.7 to 65.4% of applicants). Noting the gendered schism between applicants and recipients, Spoiling Illusions makes clear the unfair and unseen odds stacked against women’s success.

Elvis Richardson Settlement #4 (Occupation) 2021 Modified mild steel gate, pink powdercoat. 1800x1200mm Photo: Sam Roberts Photography

Shifting their gaze to acquisition practices at the National Gallery of Australia, 2014–2018, the CoUNTess found that more men were acquired than women (4,566 versus 2,070) and moreover that the percentage of women’s work that was gifted rather than purchased was higher than for men (76% vs 58%). Continuing to drill into the numbers, the CoUNTess found that even here, within this subcategory of gifted works, more men took advantage of the Australian Government’s Cultural Gift Program’s tax benefits, with 27% of women versus 59% of men gifting through the program. As noted in the book, such findings speak to the extraordinary financial and reputational discrepancies between the acquisition of men and women’s work, partly summarised by a distinction between tax offsets for men and a desire to ensure their place in the archive for women.

The authors also record for posterity some of the twists and undoing of feminist achievements in the gallery sector. The twinned examples of ‘snapping back’ to a regular, male-dominated hang of the Pompidou after elles@centrepompidou and Nick Mitzevich’s $6.8 million acquisition of a Jordan Wolfson for the National Gallery of Australia in the same breath as staging Know my Name and calling for public donations to enable the acquisition of Australian women’s work, stand out as especially egregious.

Indeed there is a push-pull-impossibility of feminist activism throughout the book, hinted at by repeated calls for the CoUNTess to do more (to also count this phenomenon, explain that result, attend to this additional intersection of bias) while others, simultaneously, take offense at being counted.[2] In turn, Spoiling Illusions is not a bragging success story of an art world righted by the CoUNTess project. By contrast, following Amy Prcevich’s observation in the 2018 CoUNTess.Report, Spoiling Illusions references the ‘CoUNTess Effect’, through which galleries in the late 2010s appeared to rebalance their representation of male and female artists, an impression only achieved through large survey shows of women’s work rather than sustained policy or procedural change. Taken together, the CoUNTess project makes the unspoken argument that gender equality requires far more from the institution than representation; deeper analysis and widespread, sustained redress is required.

Melinda Rackham #remakemistresses (4 of 30) 2020. Performance documentation on Instagram @melindarackham

Despite consistent looking and murmurations on the matter (‘If the majority of artworkers are women, can they elevate more women artists? If the art market is influenced by public art institutions, can the Government mandate equity in turn raising the profile of women artists across the sectors?’) Spoiling Illusions neither locates the root of the problem, nor sets out clear steps for its resolution. Both would be impossible. Instead, it recodes and records the CoUNTesses’ digital activities into print, warding proactively against patriarchal erasure and ensuring the work’s continued existence on our bookshelves.

As part of this archival process, Rackham and Richardson compile and expand the CoUNTess project, complementing its nationwide statistics with Richardson’s own account of the difficulties of sustaining an art career, compounded by the artworld’s inability to recognise her as both CoUNTess and artist, and more explicitly to acknowledge the CoUNTess’ work itself as an art practice. Mirroring this movement between the collective and the individual, part-way through the book its tables of gendered data and accompanying analysis give way to a silver-paged illustrated chapter that pulses with the liveliness of contemporary Australian women’s art. Both Rackham and Richardson’s art, as well as artworks by fellow counters Miranda Samuels and Amy Prcevich, appear within this silver chapter. In doing so, the authors boldly make use of the text’s platform to reiterate their identities as artists and curate themselves into art history.

The CoUNTess project began before the 2010s wave of feminist popularism in Australian art and continues beyond it. Moving through the book, I couldn’t shake the image of Richardson as a marathon runner, buoyed by friends and collaborators along her route, moving with determination on a race with no clear end. Turning to Sisyphus, I wondered might feminist activism, especially this feminist activism, be likened to an eternal labour: less futile than necessary, less arduous than radically resilient. In the text’s closing pages, Rackham and Richardson share an extraordinary creed, which motivated and informed their work, which radiates with joy, creativity, collaboration and confidence. It finishes with a twinned ode to persistence and women artists: “CoUNTess will keep counting, because women count.”

Dr Louise R Mayhew is an Australian Feminist Art Historian and the Founding Editor of Lemonade: Letters to Art, art criticism for the Sunshine state.

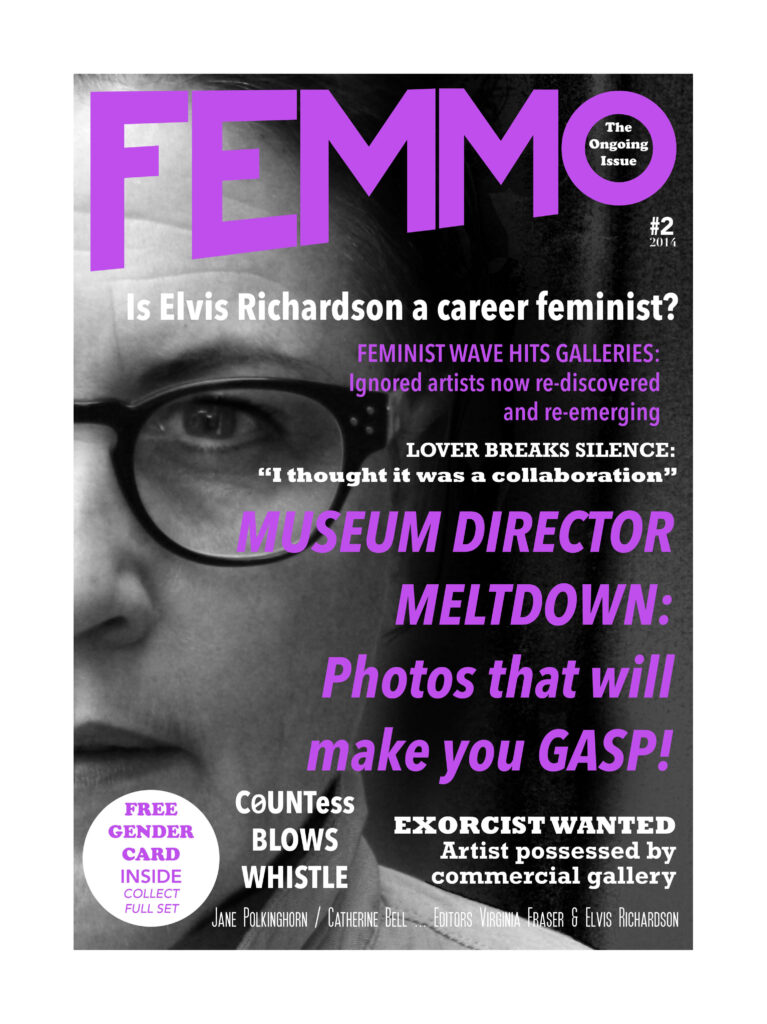

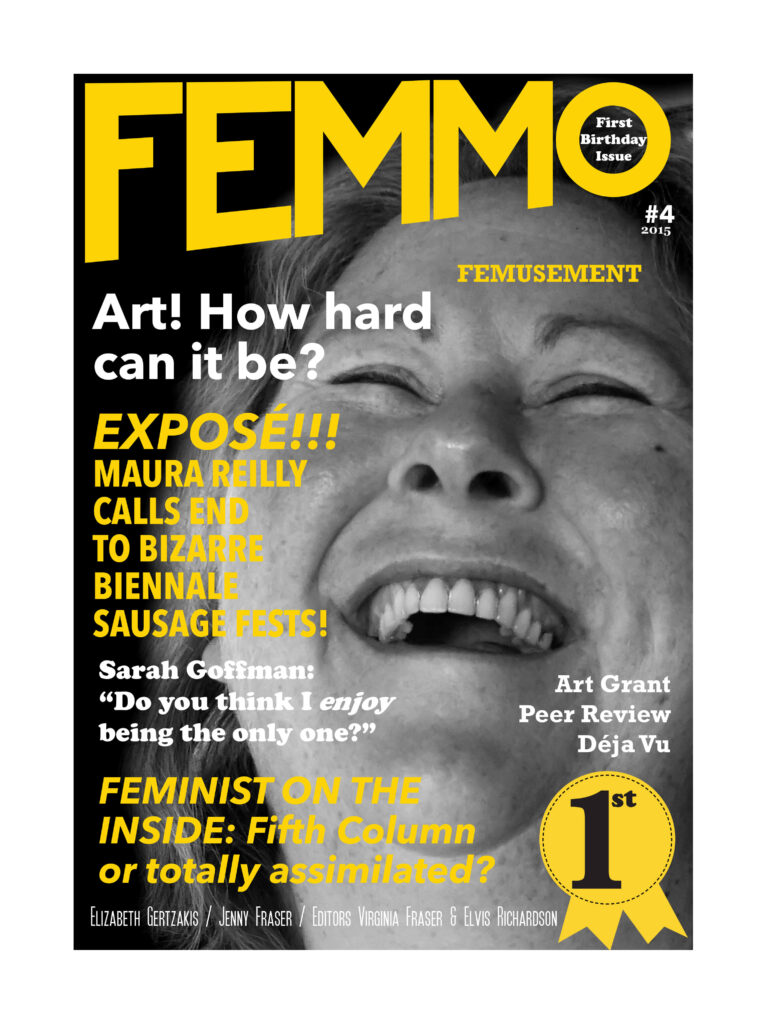

Virgina Fraser and Elvis Richardson FEMMO Issues 1,2 (2014) 4,6 (2015)

[1] Melinda Rackham and Elvis Richardson, CoUNTess: Spoiling Illusions since 2008. Countess.Report, Melbourne, 2022, 190.

[2] See especially the pouting response of TEAM Art Life to being counted in 2010, 152.