Sheila Cruthers was drawn to self-portraits painted by women artists, and much of her early collecting included purchasing or commissioning a self-portrait of the artist, which would then hang beside a work by that artist. Perhaps it was because Sheila could witness her own feelings in the faces of these women, whose experiences were rarely legitimised in a male dominated art scene, that she was attracted to women’s art and in particular the self-portrait.

Walking into the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to visit the current exhibition Jenny Watson The Fabric of Fantasy, I too felt I was witnessing my own experiences through swathes of fabric, image and text. A fusion of fantasy and autobiography, the large scale narratives feature a cast of characters (Alice in Wonderland, Ophelia, Scarlet O’Hara), alter egos and self-portraits who inhabit their worlds of the magical, mundane or everyday suburbia.

Curated by Anna Davis, Jenny Watson The Fabric of Fantasy (running until 2 October) presents a vibrant experience that transports the visitor down the rabbit hole, into Jenny’s Wonderland.

Installation view with: Eye of the Storm 1984 oil, synthetic polymer paint and coins on canvas

Ross Bonthorne Collection. Image by Anna Kuchera courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia.

Jenny Watson is a significant Australian artist who has spent much of her time overseas, travelling, exhibiting and making art. Her practice spans more than four decades, in which time she has been able to document the changing experiences of women from the 1950’s, when she was born, to the current day. In an interview with Louise Neri (p105), Jenny explains:

“…From the time I started painting as a child, I drew on my own background and experiences growing up in the suburbs. After that, I began delving into the subconscious, the world of dreams, desires, past, future – how I felt, what women think and feel. What a can of worms!”1

Having won a scholarship to attend the National Gallery Art School in Melbourne, Watson started painting suburban scenes, ‘imagery largely overlooked by artists at that point’. 2 The exhibition includes work from this early period in 1972, mostly carefully rendered realistic drawings and paintings of rock bands and the music scene. By the 1980’s Watson was developing a distinctly recognisable style that was ‘deliberately naive’ and conceptual. 3 Watson describes them as ‘first impressions’.4 Commenting on the act of painting itself and keenly aware of developing a career outside Australia, this change in direction was strategic, a response to the punk scene and the rising feminist movement of the time.

Jenny Watson, Cyclone fence with Great Dane 1972, oil and acrylic on ten ounce cotton duck. Courtesy and © the artist. Photograph by Carl Warner.

Watson met Lucy Lippard, the US feminist writer and curator, when Lippard was visiting Australia for her lecture tour in 1975, and encouraged the development of the Women’s Art Register. WAR as it was known, was a group of women artists in Melbourne who advocated for the representation of women’s art and artists in museum collections and commercial gallery exhibitions. During this period, there were a number of feminist art journals being published. One in particular was LIP, a collection of images and text concerned with feminist issues created with a homegrown aesthetic.

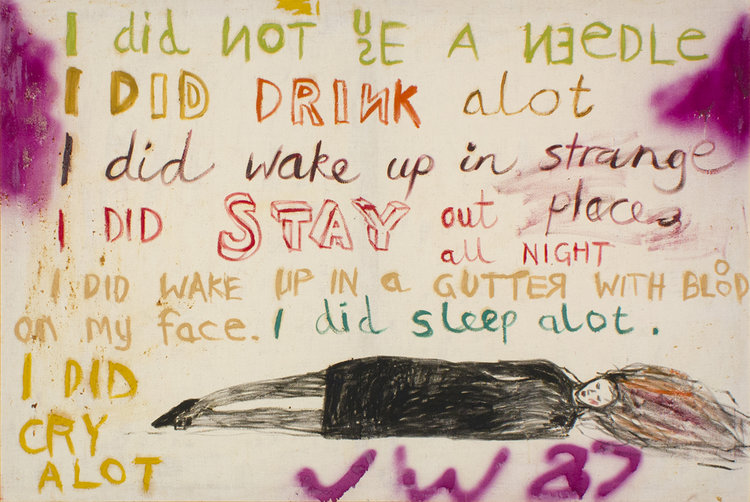

Watson often used text alongside her images. In 1980 she painted a small canvas that comprised only text, titled An original oil painting. Influenced by the work of artist Joseph Kosuth, such as his installation One and three chairs 1965, where he exhibits the tightly typed dictionary description of the word chair alongside a photograph of the chair, with an actual chair, Watson opted to use scrawly hand writing text, a direct and personal response. Watson’s use of text is reminiscent of a diary entry or the zine-like quality of many of the feminist journals of the time.

Jenny Watson, The key painting 1987, oil and gouache on cotton duck. Collection of Roslyn and Tony Oxley, Sydney.

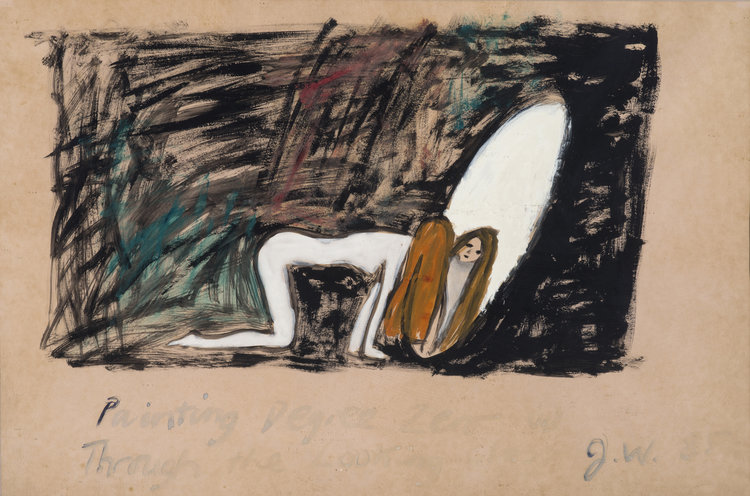

Jenny Watson, Painting degree zero 1984-85, synthetic polymer paint on brown wrapping paper. Courtesy and © the artist. Photograph by Carl Warner.

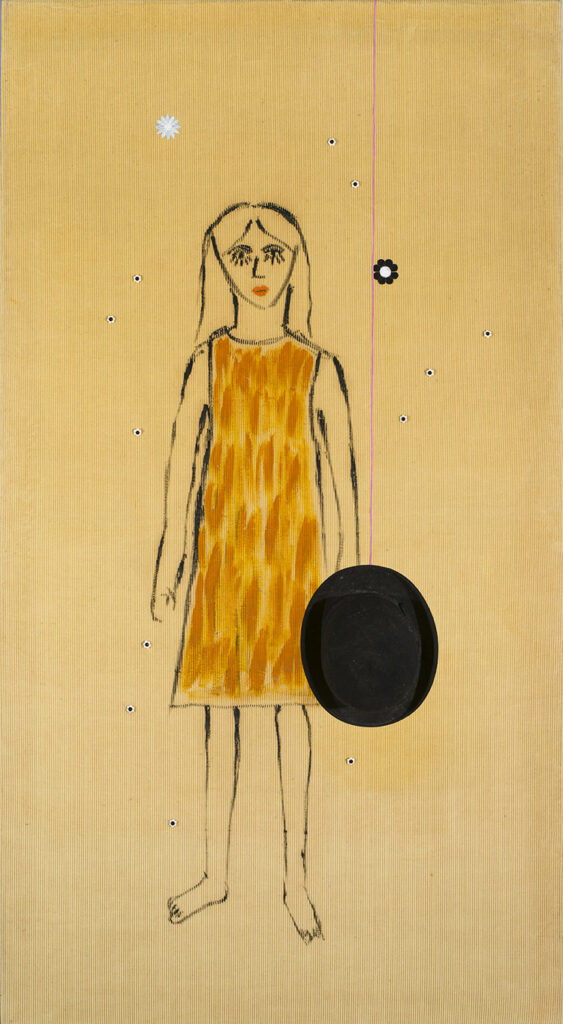

Loaded with memory and nostalgia, many of the works are painted on fabrics that have been collected during Jenny’s travels, creating a surface that imbeds themes of time, culture and place. The materials are varied in texture and meaning, from industrial thick heavy chaff bags to domestic fabrics like corduroy, sparkly taffeta, transparent voile, luxurious velvet and vintage drapery. These tactile materials have an underlying sense of the feminine and Jenny explores the idea that “women are meant to know about these things”, referring to clothes that her mother made her when she was a child. 4 Jenny’s interest in the punk scene with its op shop and DIY fashion aesthetic, plus the exposure to international artists who were experimenting with non-conventional materials, influenced this experimentation with surface. From the 1990’s, Jenny’s direct imagery simplified, while the surface became layered with found objects. This is evident in Flower child 1992-1993 oil on corduroy with found bowler hat, where the recurring girl-women figure ripples on the grooves of the velvety surfaces of the corduroy, a favourite fabric of the anti-establishment of the 1970’s and later.

Jenny Watson, Flower child 1992-93, oil on corduroy with found bowler hat. Collection of the artist. Photograph by Carl Warner.

In the exhibition catalogue text, Anna Davis suggests that the use of unconventional materials as a surface for the paintings is a “gesture as much about affordability as it was a feminist strategy and an ‘up yours’ to the art establishment.“ 5 This may have been true for Watson’s earlier works, however as Jenny’s international career blossomed, her motivations in selecting materials became an important part of her process. She sought out fabric shops during her travels and developed relationships with many of the suppliers.

The exhibition is a collection of rooms that explore the various themes that infiltrated Watson’s art practice. In the black cavernous space titled ‘Music scene’, you feel you are entering a punk concert venue. With a selection of music from Watson’s favourite bands from the 70’s and 80’s, the curator has taken Watson’s lead and rebelled against the traditional white cube, opting for a almost suffocating black bunker to display the works influenced by Watson’s passion for punk. Here the protagonists in her paintings wear black tights, short skirts and kick ass heels.

Jenny Watson, The Fantasy of Fabric installation of the “Music scene” space. Photograph by Anna Kuchera

Further along the exhibition you enter the ‘Jewel box’ room, with soft pink painted walls. Creating a domestic, feminine space, the large canvases are displayed salon style, way up high so you feel the figures are floating above and around you. This space is the antithesis of the punk bunker and represents the body of work that was created later in Watson’s career, charting the many characters and forms of the female experience.

Jenny Watson, The Fabric of Fantasy, installation photo of the ‘Jewel box’ space. Photograph by Anna Kuchera.

Jenny Watson, The Fantasy of Fabric legitimises the lived experiences of women as a subject for art making. No longer the passive model and object of the male gaze, Watson’s women chart the many facets of the female through the artist’s personal journey. Although Jenny traveled extensively, her art represents the experiences of a white women from the lucky country, one of punk, horse riding, early white American feminism, European fables, fantasies and popular culture. It is an experience that I very much identify with, however I suggest that there are others who may not. Gender aside, Watson’s contribution to Australian art is recognised in this thoughtfully curated and impressive survey exhibition.

The Cruthers Collection of Women’s of Art located at The University of Western Australia includes three works by Jenny Watson.

Jenny Watson, My mother’s kitchen 1977, coloured pencil on paper, 56.8 x 76cm.

Jenny Watson, Self portrait (Light My Fire version) for myself 1980, pastel & wash on paper, 56 x 76cm

Jenny Watson, Drink me 1988, oil and collage on linen, 137 x 106.5cm.

References

1. Neri, Louise (2017) 105 ‘Horses’ Jenny Watson in Conversation with Louise Neri, Jenny Watson the Fabric of Fantasy catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia 5 July-2 October 2017, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney

2. Hall, Sarah (n/d) Artist Jenny Watson, in her own words, Art 150: Celebrating 150 years of art, Melbourne University https://art150.unimelb.edu.au/articles/artist-jenny-watson-in-her-own-words

3. Davis, Anna (2017) 29 Jenny Watson The Fabric of Fantasy, Jenny Watson the Fabric of Fantasy catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art 5 July-2 October 2017, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

4. Ibid 38

5. Ibid 38

About the author

Felicity Martin is currently working on an internship with the Cruthers Art Foundation as part of her Masters of Art Curating, University of Sydney. Her research interest is in feminist curatorial strategies and the current acceleration of interest in research and exhibitions in women’s art globally. Martin is the manager and curator for Gallery Lane Cove and Creative Art Space. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts (National Art School) and Bachelor of Business (Newcastle University). She has curated Sister Cities: women artists from the Lane Cove Municipal Art Collection and the Gunnedah Shire Art Collection (2012), Sustainable aesthetics (2014), The Charged Object and The Aesthetics of Touch (2016) and assisted curator Jason Wing with Blak Mirror (2017), all exhibited at Gallery Lane Cove.