Now is life very solid, or very shifting?

– Virginia Woolf, Diary III.[1]

Days of Their Lives Exhibition Review by Aimee Dodds.

Days of Their Lives presents a sample of contemporary photography by eight women in the early stages of their practices. Works by Chloe Bartram, Anaïs Bellini, Yabini Kickett, Millie Murfit, Sherry Paddon, Ebony Talijancich, Erica Watkin and Chiluba Young feature in this nascent, subtle and engaging exhibition at the Perth Centre for Photography.

The exhibition is offered in celebration of International Women’s Day 2020. All-women exhibitions are the result of progressive initiatives demanding equal representation, with recent examples such the Know My Name campaign by the National Gallery of Australia, and the CoUNTess Report gaining prominence in the Australian cultural landscape. These exhibitions are small but necessary structural changes and are important in addressing the limited and limiting ways that histories of Australian art have been recorded and displayed.

On the other hand, this exhibition’s inherent tension is that in presenting eight statements of women’s subjectivity and agency –stories of their individual lives – the potentiality for those individual statements to be homogenised into a category of institutionalised difference (women’s art) occurs.[2] The didactic in the exhibition’s entry way names thematic concerns long associated with what might be termed women’s art: “challenging patriarchal narratives and refiguring traditional gender representations.” It is important to note that the eight voices in the exhibition, however, are diverse. In Days of Their Lives, photographers from differing cultural backgrounds present a considered practice that interrogates a wide range of subjects and thematic concerns. Ideas as different as consumerism, memory, the body, landscape and sex are explored through the photographic form in an exhibition that has been photographed on nearly everything from the humble iPhone to 35mm film. If the exhibition’s plurality is its challenge, it is also its strength.

The exhibition’s title, Days of Their Lives, indicates the concern for and attention to the quotidian that these photographers explore. Virginia Woolf’s question, proffered in 1941, is reflective of this concern – how one might best represent daily, lived experience in aesthetic form. The question transfers easily to the medium of photography. At once a tool of recording and construction, the lens functions both as artistic medium and pervasive tool in everyday life.[3] The photographs in the show perform a tension between these two applications, inviting the viewer to consider anew both the object of the lens and its subject.

Carefully curated connections between the works serve to highlight shared concerns between the eight photographers. A series by Chloe Bartram features four photographs: a young woman with long hair staring out of a window, seen from behind; a ghostly veil against a dark background; a curled snake on a circular table that is covered in a red tablecloth; a pale, close-up section of skin replete with dark hair and covered in sheer white fabric that could, at first glance, equally be an armpit or a pubis. They are titled Silent Protest, Wife is a Four Letter Word, The First Sin and Secret Rebellion. A fifth addition, a text panel with the title “Sexuality of the Honeymoon” describes a female understanding of the honeymoon where the bride is “spoilt,” and learns to expect a “week-day diet” in sexual matters that differs from the festive experience of the honeymoon. A motif of veiling, lace, covering and uncovering repeats throughout these works, as the text panel attempts to pin down and uncover the uncertainties and inherent societal expectations around heterosexual relationships. The snake, a symbol of temptation often associated with the negative female archetype Eve and original sin in Christian ideology, is reduced in Bartram’s work to powerlessness; asleep on a table that serves it up for the viewer’s consumption.

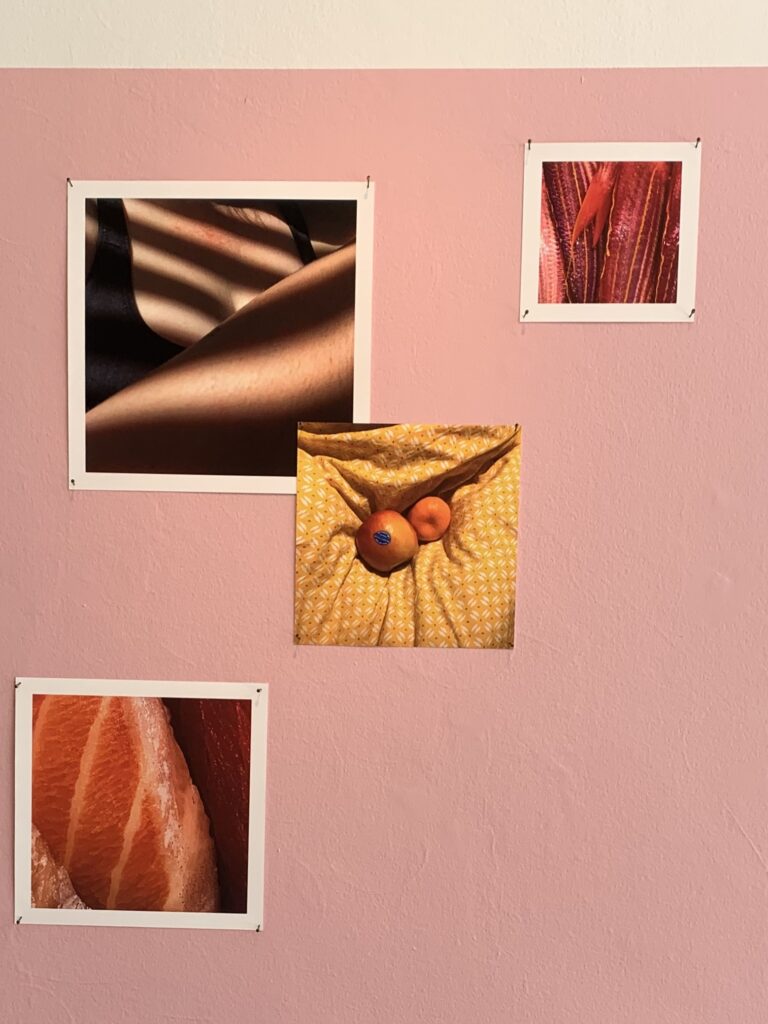

Ideas inherited through a Christian socio-cultural regime are also represented in the works of Erica Watkin. Four brightly coloured works depict close-ups of fruit and flesh, amplifying unnoticed or unseen aspects of everyday objects and playing with the notions of the female body and consumption. Exploring the idea of a “mother nature” or the stereotypical association of the female with nature, the photographs allude to the female form, to creases, to moistness. Their attempts at subversion occur through the uncertainty of what one is actually looking at, which results in a difficulty to objectify or commodify it. In the outer., it is unclear whether a close-up shot of a body and limb is an arm, which denies intimacy, or a leg, which invites it. In Harvest, fruits placed in the crease of a yellow tablecloth resemble a female, V-shaped crotch. The strength of these works is their attention to scale: micro landscapes become macro ones and force the viewer to contemplate that which is unseen or ignored, to look anew. The amplification of the quotidian references a long artistic tradition, best established by Woolf, of reifying the often-ignored daily female experience.

Simultaneously, the repetition of the codes and associations between the female body and fruit in Watkins’s work adds to the discourses of consumption and objectification that have long been explored and challenged in feminist art. The danger is, perhaps, that we are too used to seeing these codes to be confronted by attempts at their re-iteration or subversion. Against an artistic landscape which continues to champion ideas of genius and originality (often masculine), the return to these associations by female practitioners can at best be read as evidence for systems of female influence and collaboration, which can become strategies for resisting hegemony. Here the tensions in photography’s ubiquity emerge, and at worst, the artist can be criticised for employing the tropes which she seeks to critique.

Erica Watkin – ‘the outer.’ (top left), ‘Scales.’ (top right), ‘Harvest.’ (middle) and ‘the inner.’ (bottom left)

A similar conversation emerges through the works of Ebony Talijancich, Asarina (James) #1 and Asarina (James) #2. In these photographs the unretouched youthfulness of the male titular subject shines through, in efforts by the artist to subvert the ways the male form is represented. There is a real sense of touch in these photographs – the model’s hand grasping the Asarina (or climbing snapdragon) plant, the shadows and leaves caressing his face, the cold wrought iron bar pressed against his chest in the second photograph. These dreamlike works possess the gentleness of any Renaissance variation of Flora. There is also something unsettling in the works –the male subject is too close to the surface plane of the image, and gazes back at the viewer in a way that would traditionally be performed by a female subject, or considered feminist. The artist’s biography in the catalogue suggests that the project is a larger one, focusing on the amalgamation of masculinity and femininity into a “new form”. The result is troubling: attempting to grapple with the history of representation of femininity and masculinity that the portraits upend and collate is difficult. Additionally, the idea of a new form for the masculine subject reads as a trend toward post-identity aesthetics. Questions of gender identity are rife in the twenty-first century, and undoubtedly an important element of contemporary artistic practice. However, to me, this particular exploration –- presented in an exhibition that is offered in celebration of International Women’s Day, in a world where many women still struggle for self-determination (or acceptance into the categories which post-identity seeks to abolish) –reads as a little misplaced.

A thoughtful engagement with the photographic form and idea of memory is explored through the work of Millie Murfit and Anaïs Bellini. Murfit’s landscape photographs inspire a sense of nostalgia for strange, dreamlike places I have never visited: a hotel with a neon “Open” sign cast in shadows ((No) Vacancy) and a shimmering lake dotted with light (The Lake). Working exclusively on film and with rural landscapes, Murfit plays with notions of the real and the imagined. Here, photography’s inherent formal tensions emerge triumphant: these landscapes have been considered and constructed carefully by their photographer, but appear at once familiar, as if I have visited them before. The catalogue essay for the exhibition by Jenny Scott references Susan Sontag: “Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” Murfit’s work embodies this duality. The works perform a tension between recollection and reconstruction; in the act of looking at the photographs, memory is both experienced and generated in multiple ways. Bellini also cleverly plays with ideas of memory and nostalgia. Photographs depicting people sleeping under a ping-pong table, two people kissing, shot from above, and the shadow of a cat in a window appear as stills from a film, fleeting scenes of movement, a moment suspended. Bellini’s use of light is clever, and the result is an ethereal and intricate depiction of patterns and shapes that are able to be interrogated by the delighted viewer. In her hands, the shifting is made solid.

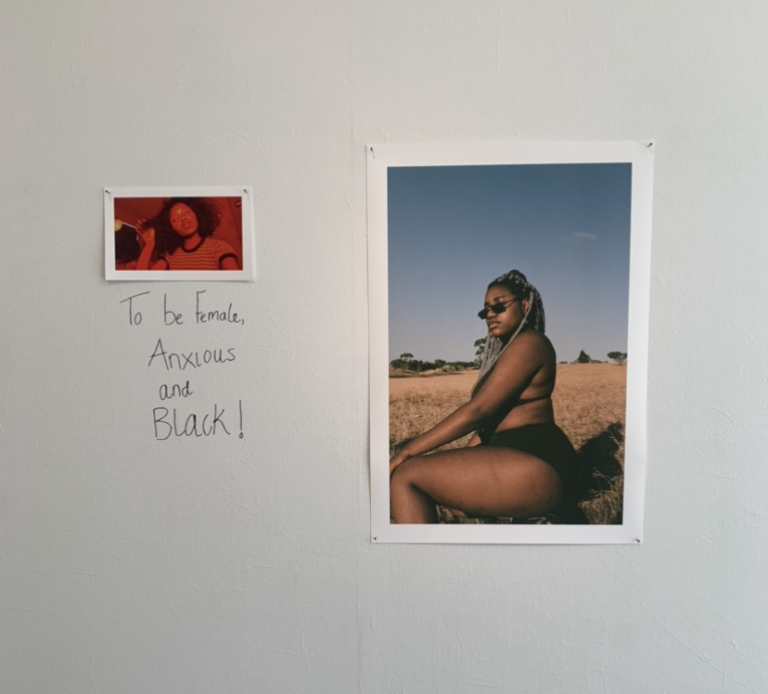

Chiluba Young – ‘Hi, How are you?’ and ‘Yarn Braids’

The exhibition space also encourages sustained engagement through the dynamic display of the photographs. Yabini Kickett’s large scale collage of Sally Field is hung high, presiding above the entry and threshold between the Perth Centre for Photography and FLUX Gallery next door. This work is a digital collage that sparkles and delights, with the words “Women of Influence” plastered atop expressive images of activist and actor Sally Field. The fruit photographs of Erica Watkin blare engagingly against a square of wall that blushes pastel pink. Two photographs by Chiluba Young, of subjects that the artist calls “people that look like me” feature a pressing textual intervention – “To be Female, Anxious and Black!” These colourful interjections and the exhibition’s thoughtful installation activate the space, invite a sustained engagement with the works, and are testament to the diversity of photographic practice featured.

For me, the highlights of the show are the photographs by Sherry Paddon. Paddon originally worked as a sculptor and this experience emerges in her works which feature assemblages of flowers, junk food, packaging and decor items. In the artist talks for the show, Paddon suggested that she wanted to replicate the visual language of advertising campaigns from the 1980s. These traits are evident in the bright colours and spatial arrangements within her photographs. Flowers emerge from a KFC bag, comedic and pathos laden, against a pale blue background. The large-scale photograph of Paddon’s daughter is a stand-out. The subject lies on her back, dressed in red against a red background. Across her little body she holds a silver tray with a bowl of Nutri-Grain, a can of Coke and a silver-lidded bowl. There is something inherently funny about this work, perhaps in the subject’s wide eyed, unperturbed stare, and tiny resigned, open hands. There is also a serious commentary about consumption, ageing, mass advertising, the hyperbolic ways and lengths corporations go to sell products that are devoid of nutrition and the ways these narratives repeat in culture. The semi-ironic title of Paddon’s work is fitting: The Weight of All Things.

“The weight of all things” also best reflects the content of the exhibition: encompassing, pervasive, and fraught with difficulty. The micro is made macro in this exhibition, and we are exposed to the weight of all things that concern these eight precocious photographers. Moments are suspended, the trivial is amplified, and the unseen attitudes which characterise the unequal relations of power between men and women are named and criticised. When Virginia Woolf asked Now is life very solid, or very shifting? in 1941, she was referring to both the nature of experience and how best to encapsulate it through an aesthetic medium. In the hands of these eight female photographers, the question is expertly placed.

Days of Their Lives runs until July 18 at the Perth Centre for Photography. More information here.

Sources

- Briggs, Julia.“ ‘Like a Shell on a Sandhill’: Woolf’s Images of Emptiness.” Reading Virginia Woolf, Edinburgh University Press, 2006, pp. 141.

- Weston, Gemma. “Gender Equality in the Museum: The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art.” Artlink, 2017.

- Crott, Emma. “Expanding the Field of Photography: Between Specificity and Plurality.” Here & Now 17, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, 2017, pp.2.