Celebrating the known, honouring the intangible

Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 27 February – 16 May 2021

By Juliette Peers

Although launched by the Art Gallery of South Australia two years ago, Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment, an exhibition and substantial catalogue, remains current and relevant in terms of tracking institutional attention directed to non-living Australian women artists. The reach of and audience for The Present Moment was undeservedly curtailed by the Covid epidemic, but the catalogue importantly still extends understanding of the artist by offering a deeper mining of Beckett’s ideas world than yet published. Therefore The Present Moment is essential reading for anyone interested in either Beckett’s life and work or the broader picture of historic Australian women’s art. Ironically, given the relatively small corpus of publications around non-contemporary Australian women artists, Becket notably continues to attract art writers and curators ahead of other significant and engaging female artists, with a major new Beckett exhibition opened at the Geelong Art Gallery on 1 April 2023 and a full length biography published by Edith Ziegler late in 2022.

Public galleries in Australia have in recent years increasingly taken on the challenge of raising the visibility of women artists in their collections, permanent displays and exhibition programs. Broadly speaking exhibition events that directly focus on Australian women artists seem to fall into two basic categories. Often we see large group wunderkammer style clusters of works brought together in transhistorical juxtapositions that somewhat evade the tedious drag or the responsibility of making any further attempt to draw patterns and commit to any depth of sense-making. The popularity of such anthology shows perhaps reflects the new dominance of image-heavy communication formats nurtured by social media that downplay textual content and long attentive thought and reading in favour of scrolling through a plethora of visual moments and sensations. Also perhaps the focus on prioritising sensations centred on the visual and the tangibly close offers a youth-facing platform of immediacy that serves the needs of makers and the increasingly central power of young consumers. Equally, in an era of mandated de-colonisation of cultural expression, the focus on the directly present tangibles of live artworks and making evades the heavy weighting of textual records, especially in a context of reviewing the past, towards “whiteness”. This weighting could be happenstantial as much as malicious, but today is routinely assumed to be of malign intent. Any backstory or extended story inconveniently and inevitably implies the a priori horrors of colonialism and therefore the wholesale stripping of meaning and nuance is often welcomed as a positive development. Perhaps we are also witnessing just a new reiteration of the – in my opinion – often overrated and manipulated construct of the text being somehow a betrayal of the artwork and the artist and especially wrongfully deflecting attention from the I-message of the artist’s statement, which for some people is the only writing that needs to be appended to an artwork.

Clarice Beckett, born Casterton, Victoria 1887 died Sandringham, Victoria 1935. Bathing boxes, Brighton 1933, Brighton, Melbourne, oil on board, 17.5 x 22.0 cm. Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide ,20197P110.

The second dominant paradigm is the biographical or monograph show, which has traditionally involved an elaborate, well researched and generously illustrated catalogue, summarising the current state of scholarship and which represents the accepted standard account of a given artist for years to come. This approach is most frequently directed to major male artists and became a standard on public gallery calendars in the 1990s, growing out of and subservient to the booming Australian art market of the 1980s. Equally these grand catalogues reflect a de facto synchronisation and networking amongst major institutions and major curators as to the timing and content of each event and as to which institution would act as the organising gallery. Decades have passed and there has been in the case of some major figures a second generation of similar self-consciously benchmarking exhibitions centring on iconic male artists, revisiting their work and rethinking 1990s interpretations in the 2010s. Amongst the few shows of historic art by women that match the official care and attention directed to male artists were the excellent shows on Margaret Preston by Deborah Edwards, Denise Mimmocchi and Rosemary Peel, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2005 and on Dorrit Black by Tracey Lock, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2014. Two shows that examined women artists as equals to iconic male artists could be mentioned in this context too – the QAGOMA exhibition of Ethel Carrick and E Phillips Fox Art, Love and Life, 2011, and the NGV show of Nora and Hans Heysen, Two Generations of Australian Art, 2019, as well as some highly effective shows pitched at a slightly more intimate level and yet also seeking to track the artist’s whole career and impact in a larger context such as National Gallery of Australia Grace Crowley exhibition, Being Modern, 2006-2008 (hampered by a fragmented oeuvre) and Heide’s Erica McGilchrist survey exhibition For the Record, 2019 (for a versatile and capable artist whose reputation has remained somewhat off the mainstream).

The recent Clarice Beckett exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia The Present Moment, 2021 can be added to that small cadre of shows that approach a woman artist’s life and work with both the fine grained insight and rigorous responsibility in handling the material that is routinely directed towards narratives around male artists. The rarity of such satisfying and rewarding presentations of women’s art is not due solely to curatorial incompetence or lacks. Moving back past the 1970s, the number of women artists for whom sufficient artworks and documentary material can be mustered to assemble a show that informs an extended understanding of the artist, setting out her place beyond question, is relatively small. The lack of material or contextual richness is not due to the artist producing few works during her lifetime nor lacking sufficient profile amongst her contemporaries. Archives, libraries and old newspapers are full of women exhibiting, often annually, sometimes with 100 or more works in an exhibition, women receiving commissions, being bought by public institutions, organising art schools, chairing committees and running businesses, breaking out from expectations. However years of watching auctions and gallery sales frequently only reveals a handful of works attributable to women who may have spent an active three or four decades in the public eye. This high profile of women artists amongst their contemporaries in the past is not the strawman world of popular construct where women artists and their works are irrelevant and unimportant productions from some fictitious Victorian/Edwardian parlour, where frigid genteel spinsters of solid means hide behind lace curtains.

Works by these past women artists did not disappear spontaneously into the mist like Brigadoon nor explosively self-destruct like the tape recorders at the start of the 1960s television series Mission Impossible. Input from “experts” orchestrated the coups de grace, experts advising an executor of an estate to burn large Jane Sutherland paintings that had in their opinion neither aesthetic or historic merit, auctioneers likewise advising that the large inherited collection of paintings would not recoup the cost of a sale, or curators deaccessioning works from public collections that were deemed to have no merit. Given the fragility of women’s reputations and their sometimes marginal status in dominant narratives, women and their cultural products often bear the brunt of deaccessioning policies in Australia. Public galleries have deaccessioned women as diverse as Clarice Beckett and Phyl Waterhouse. That is why I am always opposed to deaccessionings, even though they are presented in present day curatorial studies courses as needed and desirable for the management of collections. In recent years, deaccessionings are advocated for providing financial resources to enable more diverse purchases of contemporary art, as is currently a popular trend in the US, thus the removal of unwanted, supposedly unworthy, art is not just a matter of taste, but also of correcting past social-political error.

Clarice Beckett, Walking home c. 1931, Melbourne, oil on canvas on board, 49.2 x 59.5 cm. Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 20197P99.

To be honest, my heart sank at the thought of yet another Clarice Beckett exhibition when so much women’s art history remains uncelebrated and still off the public record and the public imaginary. On the face of it, there seemed relatively little need. I am one of the few who have gone on the public record as finding the popular social discourse that has wrapped itself around Beckett’s art as a burdensome overlay, distracting from the works themselves.[i] However in that context, the Art Gallery of South Australia’s recent Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment exhibition by reading the evidence of Beckett’s art and life with a greater restraint, accuracy and analytical discipline than before deserves much respect. The Present Moment makes a completely valid case for yet again presenting Beckett’s work to the public. Here finally discussions of Beckett had a persuasive cogency often previously missing in academic and curatorial terms. Moreover it is the first interpretation of her work that does not accept it on face value as a romantic ineffable detritus of an almost other worldly genius, but seeks to analyse and parse what Beckett was seeking to do and map the ideas and processes that were inherent to her achievements.

The familiar dialogue between the art and the curatorially endorsed myths of Clarice Beckett was triangulated by the introductory interpretive space of The Present Moment which featured memorabilia, some drawn from Beckett’s surviving heirs, wall texts and captions that alluded to Beckett’s professional connections to artist contemporaries and her intellectual concerns, both of which provided a robust foundation for Beckett’s self confident effectiveness as an artist. Her astuteness and control is generally downplayed in the usual discussion of Beckett as wounded victim. Throughout the spaces of the exhibition captions and wall panels provided a more lucid explanation of Beckett’s technical and intellectual rigour and offered cogent and fresh understanding of the artworks themselves. The combined impact of these framing words substantially exorcised the insidious irrelevant concept of Clarice Beckett as a hapless idiot savant, buffeted by sexism, patriarchy and family obligations, who had stumbled onto a proto modernism.

Tracey Lock’s catalogue essay, whilst it tacitly endorses the dominant biographical myths (more so than the physical exhibition itself), equally takes discussion of Beckett’s art to compelling and original new dimensions in suggesting that Beckett’s long-term engagement with Theosophy provides the key to both her subjects and motivations. Theosophy offered Beckett with a pathway to a more spacious and questing understanding than that held by many of her Australian contemporaries of what art could be and could achieve. Beckett’s self-directed exploration of spiritual consciousness and reading of works by Helena Blavatsky, Annie Besant, and possibly related texts such as Rudolf Steiner and Goethe’s theories of colour, opened up a complex and diverse cultural world and aligned her with a global resonance of then avant garde thought. In a reverse move, foregrounding Beckett’s links to radical beliefs of the early 20th century, which were both internationally resonant and culturally syncretic, rather than imperially hierarchical, offers a potentially more dynamic and cosmopolitan placement of the art of settler Australia as having a legitimate merit beyond the habitually inward-turning nationalist and regional values (both right and left) of Australian art practice and equally positing a greater intrinsic importance for Australian art at a global level.[ii]

Alongside explicating Beckett’s intellectual parameters the catalogue formally probes Beckett’s technical and compositional practices to a greater degree than previous literature. A number of recurrent tropes are revealed, particularly the occasional deployment of the proportions derived from the Golden Section, the arrangement of the compositions by (often fairly explicit) grids and the pushing of important subject devices to the edges of the picture plane. Some of the associations in her subject matter have longstanding traction in western art traditions, such as the symbolism of moonlight, sunlight, light and dark, calm and turbulent waters. Others are more directly linked to the esoteric literature that she read, particularly Helena Blavatsky’s ideas on the vertical line as masculine and the horizontal line as feminine, with the intersection of the pair representing a spiritual whole, equally the vertical line is truth and the horizontal line is beauty and again their crossing represents a point of profound spiritual resonance and power. For a number of decades it has been art historically acceptable to link these concepts to the art of Piet Mondrian and his early deployment of abstraction, but Lock demonstrates their centrality to many of Beckett’s compositions. Beckett often takes the visual signs of suburban modernity and its constructed environment, street lights, telegraph poles, railway stanchions, awnings, roofs, railings, public benches, placards, jetties, beach umbrellas, even land and sea vehicles as the tools from which she constructs her interplay of the fundamental cosmic energies.

Clarice Beckett, The Railway Track c. 1930, Melbourne oil on board 29.0 x 38.3 cm. Donated by The Hon R P Meagher through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2011, Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney, UA2011.18.

Curiously Beckett’s peculiar and haunting power as well as the tangibility of her works (that tangibility as much as her abstraction is certainly a griffe that prompts much popular enthusiasm for her work) derives, as the catalogue suggests, from the synthesis of her personal interest in esoteric beliefs with the practical and atheistic, pro-science teaching of Max Meldrum, who boasted that he descended from generations of free thinkers and agnostics. Theosophy and Australian tonalism/Meldrumism were at once both antithetical and mutually supportive. Whilst Meldrum emphasised the systematic and analytical approaches to art: correctly capture the basic and tangible tonal values of what is before the artist, and the illusion of space and form will consolidate itself for both artist and viewer, he also outlined a construct of the world as an essential unity, in his case by tonal value rather than spiritual forces, unlocked by a disciplined concentration, and also (in a parallel manner to achieving enlightenment or a more refined and spiritual consciousness) by attentive repetition of exercises, self-critique and self-awareness. Beckett had been exploring both art studies and her interest in spiritualism and eastern religions from c 1900 onwards, but a relatively short, nine months period of study gave her the means to bring these ideas into a tangible painterly form.

The organisation of the exhibition space not by chronological date, but ordering the works in terms of the passing of a single imagined archetypal day clustered the works thematically and in terms of their shared colour palettes, tonal register and subject matter. Curatorial choices here offered (which they so frequently fail to do) fresh nodes of engagement and ways to frame both artist and practice. Rather than despair or frustration at inhabiting a life that others demanded be frittered away for their personal agendas, Beckett created a world that was at times surprisingly social, sunny and bright and by no means melancholy. The people whom she observed, often at Melbourne’s bayside beaches, were happy and relaxed. As well as sinister brooding male figures, women and children inhabit her spaces. Her ability to observe and communicate gesture, stance and mood through a few semi-abstract brushstrokes not only is remarkable in itself, but also suggests a degree of empathetic outreach missing from the formalist aspects of the Beckett legends which celebrates her almost unconsciously pulling a semi-abstract ordering of the world and her canvasses out of thin air. Theosophy taught a pantheistic vision of a holistically sacred physical world in which all living and observable phenomena were manifestations of the same sacred entity, joined by invisible forces. Beckett’s works are a product of her openness to and respect for this sacred continuum, each one is in effect a prayer, a mantra, an act of devotion, and as the catalogue suggests each painting was “a self-renewing act”. [iii] The formal division of the imagined day presented in The Present Moment suggested the ordered daily timetable of a monastery, convent or lamasery.

Clarice Beckett, Beach Scene c. 1932-33, Melbourne, oil on canvas, 52.1 x 62.0 cm. Private collection. Image courtesy of Deutscher and Hackett.

This grouping of works by the time of day defied the complaints of early critics such as Blamire Young and J.S MacDonald that Beckett’s works were dull and monotonous in their insubstantiality and lack of focus. A large tranche of sun-filled noon days scenes were revealed, as well as pale dawns, golden sandy beaches, rosy pink sunsets and the abstraction of the pastoral landscape in the sparse and yellow Naringal scenes. Most surprising was a series of wilder, more expressionist works, with dark strokes on light backgrounds, the gestural freedom of the darker lines resembling Asian brush painting with ink. Most of these works were evening seascapes where the moonlit sea provided the light background for the ti tree and vegetation to appear as dark silhouettes. This pictorial drama and vigour is generally absent from more standard Meldrum works. The careful choice of works for The Present Moment ensured that, large or small, they spoke with equal authority. From work to work her complex, superbly judged and balanced geometries, the abstracted shapes of shadows and outlines were repeated flawlessly without becoming monotonous.

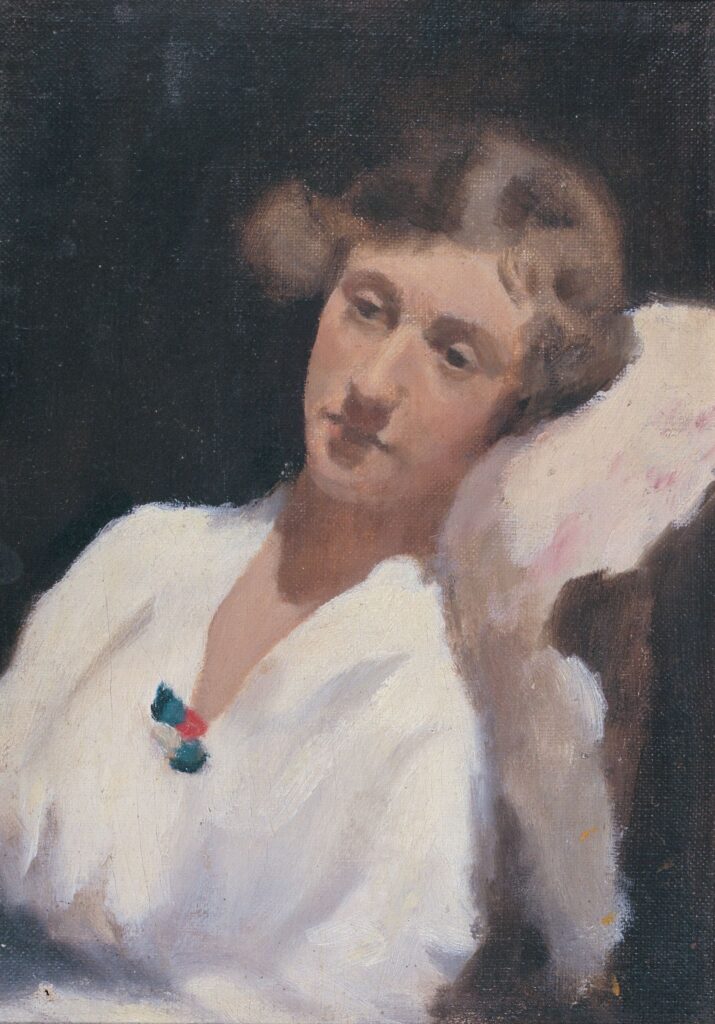

Clarice Beckett, Portrait study (Hilda), 1918, Victoria oil on board, 26.5 x 18.0 cm. Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia.

The central space, neatly fitted out to resemble a 1920s kitchen as a reminder of her father’s refusal to build a studio saying that the kitchen table will do, offered works that presented a more social dimension to Beckett’s art. The two portraits of Hilda, amongst her few actual figure paintings to have survived; she consciously refused to progress to the traditional life class and figure painting offered by Bernard Hall at the National Gallery School, show two different moods. The 1917 portrait of Hilda in the Cruthers Collection comes closest to the stark uncompromising sharpness seen in a number of Meldrum’s key early pupils, the colour scheme is virtually monochrome, and shadows interrupt the expected reading of the face and shoulders and defy conventional notions of female portraiture. The 1923 portrait is more evenly lit and the detail of dress, headband and jewellery suggests a more worldly and fashionable ambience. The direct plainness of the 1919 still life of Fish, Plate and Bottle from the Stokes Collection again suggests the early revolutionary fervour of the Meldrum group, close to the era when Meldrum was accused of being a pacifist and a traitor to the Australian war effort and drunken soldiers would angrily attack his studio. The flower pieces are also more clearly integrated into the preoccupations of the broader Meldrum circle in which, contrary to stereotype, Clarice was a notable and respected member. Her friend Beatrix Hoile Colquhoun was renowned for scavenging early oriental porcelain from Melbourne junk shops and the Little Bourke Street “China Town” and triggered similar activity amongst almost all of the tonal group, which was often reflected in their still-lifes. Likewise as the catalogue and signage noted, the flowerpieces were her response to her friends John Farmer and Polly Hurry’s engagement with Japanese culture. They presented a Japanese tea ceremony in Beckett’s honour and shared a knowledge and practice of Ikebana, decorating their home in Olinda, Miyako, in a Japanese style with seasonal displays of flowers. The Pavlova studies, part of a series that Beckett painted, are a reminder of the importance of theatre, music and even cinema in her life. These works should be understood in terms of Beckett’s own seriousness and confidence in herself as an artist. They are a tribute from one supreme professional to another. Pavlova was not just a performer with a global stellar reputation, lauded in the Australian press, she was famed as having a quasi-religious devotion to her artform above all else, and being a proselytising missionary figure, creating new audiences for classical ballet across Asia, rural North America, Latin America and Australia. Pavlova also shaped and ordered her creative presentation to her own taste, displaying a perfected talent in emotionally inflected solo mood pieces encompassing an “impression”, in the manner of a Debussy piano piece, rather than bravura acrobatic displays.

Clarice Beckett, Pavlova, Divertissement, 1929, Melbourne, oil on board, 21.8 x 29.5 cm. Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 20197P114.

A notable feature of The Present Moment was the embedding of the individual works into an extended and emotively inflected installation that had its own character and presence. Like choralography, creating hypodramatic settings for historic artworks more often than not fails as the intrusive, unredeemed banality of the driving concept is mercilessly revealed. However, in The Present Moment, abstracting the cliched legends that are associated in the public mind with Beckett and then moulding them into an immersive installation, acknowledged and served the “fanbase”, by offering an engagement with popular perception and fascination in the spirit of a gesture more frequently associated with genre fiction and science fiction and the audiences for these literary modes. The setting also offered guidance as to how to see and approach the works evoking the ritualistic fashion in which Beckett herself made them. Her use of colour was amplified by the wall painting, individual works were framed and celebrated by the cut outs, portals and room dividers. Whilst I personally find it irritating, [iv] Beckett’s live status in popular public memory as a story of loss and destruction is as important and famed a public artwork as her paintings themselves. Public engagement with her art has always expressed a dimension greater than the obvious. She provides an existential metanarrative for many Australians, especially older women, a touchstone, a catalyst to contemplating creativity, memory, value and loss and also processing stories of disappointment and lost opportunities. She is a publicly comprehendible face of feminist understandings of the art market and art history. Certainly the exhibition greatly resonated with the public: my edition of the catalogue is from the third printing in 2021 alone. Many of the attendees who queued up and thronged the gallery were of a senior age group, for whom Beckett’s presentation of a suburbia of few cars, grassy treed verges, ambling paths, garden flowers, bus stops and small local businesses would be a tangible memory from at least their childhoods. Whatever her own original intentions were as an artist, in recent years Beckett’s works act to both console viewers for existential losses and disappointments in life, yet simultaneously confirm and validate a lived experience that rarely is foregrounded by public institutional culture. The multimedia components of the exhibition, a mesmerising view of a ramshackle open shed in the changing light of the passing of a day and extended filmed interviews with Rosalind Hollinrake, both acknowledged the story, but kept it separate from the art itself.

The Present Moment managed the discourse around Beckett with a greater degree of insight and breadth than the 1999 touring exhibition seen at a number of major galleries, Politically Incorrect. In that case publicity and signage exaggerated and hyperbolised Beckett’s disjunction from her friends and peers, as well as broader trends in Australian landscape painting, and set her in a tendentious and not fully historically accurate battle against a reductive construct of academic art trends in the 1920s and 1930. Both art professionals, who should have known better, and the quality end of both print and electronic media in Australia endorsed this over-dramatisation. Dedicated exploration of the larger network of Meldrum tonalists and their works has given me a perspective that cancels some of the romantic concepts of isolation and inexplicability of her art, as whilst she may transcend her peers, she is never fully dislocated from them nor alien to their activities and aesthetic. Tracey Lock’s previous experience in curating Misty Moderns: Australian Tonalists 1915-1950, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2008, reintroduced the larger circle of tonalists to a substantially sceptical audience, finding ways in which to cut through entrenched prejudice and indifference on the part of Australian art professionals, given that out in the burbs, third and fourth generation tonalists still find buyers and willing pupils. This continuum is also part of the backstory of Clarice Beckett’s art. A final essay in the catalogue offers an overview of what Beckett drew from tonalism and how it supported her.

In terms of her historiography much of the early reception of Beckett in the 1970s tells a slightly unpleasant story of a degree of smug but empty, over-constructed self-fulfilling value judgements by luminaries who defended a vision of radical art centred on their opinions and their careers and which was substantially intolerant to outlying and alternative views. Beckett emerged from what they defined as alien territory. To that end Beckett’s reputation benefited from the happy timing of the high status then accorded to the art of Mark Rothko at the time when her art returned to professional notice in the early 1970s. Rothko’s subtle veils of paint and suggestions of landscape in his abstractions provided a useful pathfinding device to evaluate and endorse the unexpected revelation of Beckett’s art, which was unknown to curators and critics whose main focus was living contemporary artists. At the date of the very first posthumous Beckett exhibition in 1971, feminist arguments about hidden women artists and the hostile nature of both curating and art dealing norms towards women had made little inroads into mainstream art debate.

Tracey Lock wisely acknowledges that there are multiple modernisms and multiple contexts and modalities in evaluating art, and this openness also shifts the foundations of The Present Moment. As Lock notes Beckett’s spiritualised devotional optimism, sincerity and generosity contrasts with an increasingly disturbed and divided public sector in a hostile and disordered world and can offer some solace and succour. The luminosity and transience that can be read into Beckett’s art itself acquired an unexpectedly tangible dimension as the retrospective was organised and put on show against the extreme and unusual contingencies provided by the Covid epidemic. The much-anticipated Hilma Af Klint exhibition in Sydney at the Art Gallery of New South Wales that would have been such a perfect complement was deeply impacted by lockdowns and restrictions on travel and gatherings. Within days of me travelling to Adelaide and back to view The Present Moment, Victoria again went into lockdown, and had I hesitated or waited for a later date I would have missed this significant and moving exhibition.

[i] Juliette Peers “I am Woman, Hear me Weep,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, vol. 1, no. 1, 2000, pp 213-222

[ii] The Swedish landscapist Ivan Agueli also presents a similar landscape vision to Beckett as subtly blurred and spiritually infused see Tracey Lock The Present Moment: The Art of Clarice Beckett, Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia 2021, p 50

[iii] Lock, The Present Moment, p 32

[iv] Peers, I am Woman