Rodney James is a curator, art consultant and writer specialising in 19th and 20th century art writing and research, collection management, exhibitions, visual art projects and museum policy and strategy.

His most recent publications include Una Deerbon: Australian potter 1882–1972 (2019), the first monograph on the art and life of this pioneering mid-century artist, and Letters to a Critic: Alan McCulloch’s World of Art (Melbourne University Press, 2023).

Having recently completed a monograph on critic Alan McCulloch, author and curator Rodney James is honing his research on 20th century Australian women artists, including Roma Thompson, Mary Cecil Allen and Mary Cockburn Mercer.

Rodney’s interest in Scottish born, Australian-raised and French-inspired; Mary Cockburn Mercer (1882–1963), was piqued during research undertaken for the survey exhibition, Janet Cumbrae Stewart: The Perfect Touch, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, 2003. As the curator, Rodney was made aware of family apprehension (and wider industry debates) surrounding Cumbrae Stewart’s relationships with women and how this may or may not have impacted upon her art – a focus of Juliette Peers in her erudite catalogue essay. One of these other women included Mary Cockburn Mercer, a fascinating artist – who James resolved to learn more about.

Image: Rodney James portrait. Photography by Mark Ashkanasy. |

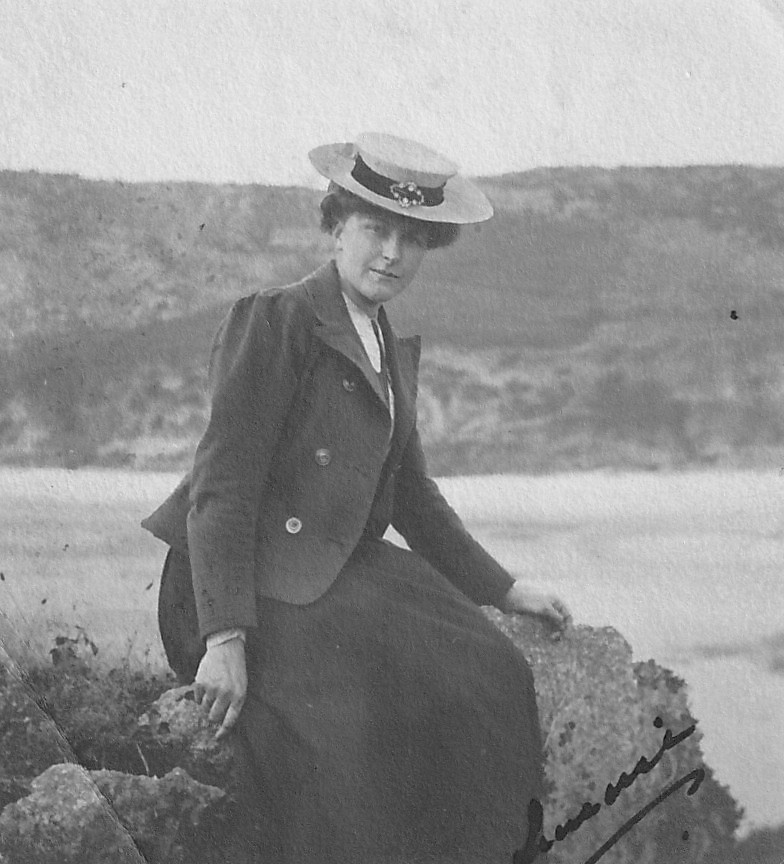

Image: Mary Cockburn Mercer as a young woman

Through his research to date Rodney has compiled a list of over over 100 artworks and many more photographs from what previously appeared as a much smaller oeuvre. MCM’s innovative French Salon and Cubist inspired paintings produced between 1911 and 1929, dreamy Tahitian landscapes from the 1930s, and elaborate allegories, portraits of friends and art colleagues and of course her racy (female) figure studies from the 1940s, paint a complex story of a neglected but multi-layered artist.

Through his planned monograph and catalogue raisonné, Rodney hopes to correct the many misconceptions (and untruths) about her life and place her art with that of contemporaries. By also making use of recent feminist and queer theory and showcasing a wider cache of her work, it is hoped a new and fuller picture of her art and life will emerge.

The visually arresting 1940s portrait of a friend, Kathleen Schlitt: a Romantic Portrait is a case in point (see below). Exhibited at Melbourne Contemporary Artists – Annual Exhibition, Athenaeum Gallery, Melbourne, November 1942, but listed as not for sale, the painting was praised by Sun critic Adrian Lawlor: ‘Miss MC Mercer brings out her extraordinary talent for lyrical distortion in her portrait, Kathleen Schlitt, a piece of expression both strong and feminine in statement.’

It is these things and more – an exercise in dressing up and masquerade, a homage to a friend who supported her, an exemplar of MCM’s larger-than-life studio practice and a coda to the continuing influence of and experimentation with early 20th century artistic styles.