Cynthia Nolan: A Biography

M. E. McGuire

Melbourne Books, October 2016

Hardcover $34.95

Available from http://www.melbournebooks.com.au/

The last few years have witnessed a new tranche of revisionist scholarship around women in Australian modernism. Even though curators, dealers, academics and postgraduate students have researched women’s contribution to modernist culture in Australia for four decades, recent projects reveal that many major female modernist advocates are still unfamiliar. New opportunities for closer examination of more obscure source material around better-known women arise as digitisation of on-paper records is unlocking more information. In recent years the art of Mary Alice Evatt and Moya Dyring has been seen in curated retrospectives. A series of new biographies have been published on modernist agents including Cynthia Nolan and Moya Dyring, along with a collection of case studies of entrepreneurial creative expatriate Australian women, from the well documented to the obscure but important such as Clarice Zanders, under the title of Awakening. [i] Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan’s finely detailed examination of the women of Heide comprises a significant tranche of scholarship. Studies of Sunday Reed’s kitchen and garden practices as well as the biography Modern Love, and the small but delightful interview with Pauline McCarthy published as the catalogue Those who made and those who saw 2008[ii], all have provided much clear-eyed information beyond the myths and stereotypes clustering around the Heide circle’s creative and gendered dynamics. This new Heide scholarship deserves attention in a future blog entry, as too Awakenings and the Moya Dyring biography, [iii] and these publications will be discussed. This current essay looks at an important but lesser known figure from the Heide circle, Cynthia Nolan.

Cynthia Reed c1925, Reed/Heide Photography Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, photograph: Ruth Hollick.

For too many years Cynthia Reed Nolan (1909-1976) was barely mentioned in accounts of Australian modernism. Mostly identified as the sister of John Reed and sister-in-law of Sunday Reed, she is actually a significant conduit of modernist culture and avant garde ideas into Australia in her own right. Her relationship to her more famous kin was complex, running the gamut from near symbiosis to longstanding alienation. She was an intrinsic part of Heide, but later did not communicate with John or Sunday for three decades. Towards the end of his life, John notably affirmed Cynthia’s role in the Heide cosmology as “Sunday’s best friend”. [iv] Undoubtedly Cynthia shared many opinions and habits with John and Sunday from commitment to modernism to the love of gardens to a bohemian, but highly aristocratic, taste.

Heide viewed from the trees c.1949, Estate of John Sinclair, reproduced courtesy of Jean Langley. Photograph: John Sinclair.

Generally since historians rediscovered the “Angry Penguins”, Cynthia has been somewhat detached from the main Heide story. Historians’ and curators’ sidelining of Cynthia falls into what Natty Thomas declares as curatorial malpractice.[v] Much is lost in our understanding of the emotional dynamics of the Heide group without Cynthia. She was the only bridesmaid at John and Sunday’s wedding and the centre of subdued but malicious gossip in Melbourne that implied, in view of the modishness of Freudian symbolism, that John Reed’s choice of wife was incestuous rather than oedipal: he was “marrying” his sister, not his mother. This gossip put a shadow over the interaction of John, Sunday and Cynthia, especially due to Sunday’s belief that Cynthia had fuelled the speculation. Yet even after the unpleasant gossip was aired in the trio’s ongoing correspondence, the expected Heide rituals are enthusiastically kept up: birthdays marked and celebrated, presents sent by Sunday and seeds and cuttings collected whilst travelling sent back to Sunday for the Heide garden. Newly released films and modern clothes, “slacks” and “woolies”, were favourite topics of discussion in the letters. Most significantly, Sunday appears to have wished to adopt Cynthia’s daughter Jinx in the early 1940s, as she would actually do Sweeney Tucker, just a few years later. Sunday’s request, along with unasked-for advice on life and motherhood generally, drove Cynthia to move to New South Wales, but not before she warned Sydney Nolan also to get out and escape the claustrophobic controlling Heide dynamic. Simultaneously the many synergies, as well as tensions, between Cynthia and Sunday makes the story of their friendship especially compelling.

Albert Tucker, John and Sunday Reed 1943, gelatin silver photograph, 40.4 x 30.6 cm, collection: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, gift of Barbara Tucker 2001.

Cynthia’s years in the early 1930s as a gallerist and promoter of modern design and interior decoration in Melbourne have been well covered, especially in relation to the emergence of pioneering abstractionist Sam Atyeo. She showed artists as diverse as Ian Fairweather, Margaret Preston and Thea Proctor and also provided a decorating and mural painting service, commissioning artists in her circle on behalf of her clients and promoting the furniture maker Fred Ward. Otherwise she appears in the autobiographies of eminent male Australian contemporaries such as Geoffrey Dutton, John Olsen and Barry Humphries as a “vampire”, gatekeeper and watchdog, keeping fans and foes alike away from her genius husband, Sidney Nolan. Charmian Clift imaged her on equally unflattering terms in her novel Peel Me a Lotus (1959) as a craggy-faced, aloof Medea furiously writing letters to people of importance who could assist or promote her husband. Sense-making professionals in the Australian arts industries – academics’ and curators’ – de facto acceptance of and complicity with these belittling, misogynist and ultimately inaccurate constructs of Cynthia, until recently, offers demonstration of the poor traction that feminism has had in the foundational values of Australian public culture. Whilst there are gestures towards feminism in both the academy and public art galleries and many historical interventions around exhibitions of female-led modernism over the past four decades, the masculinism of many major texts and exhibitions around postwar Australian art remains an uncritiqued norm, that forms the basis of academic curricula and public gallery programs. Sadly counter projects to the heroic legends such as The Field exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (a Kelly, bride and landscape-free zone) were no more receptive to female artists than the standard stories. Equally the historical void around Cynthia indicates the tendency towards repetitive blandness, the focus upon the known, accepted and familiar that dogs both literary and visual sense-making and publication industries in Australia. Above all the lack of even curiosity about, let alone respect for, Cynthia documents the unwillingness in a small pond to directly challenge the pre-selected curriculum or the authoritative voices of respected institutions and personalities.

Historically Cynthia has often been cast in the public eye as the evil “other woman” who broke up the affair between Sidney Nolan and Sunday Reed, often viewed as not only a sexual relationship, but also the source and driver of the best of Nolan’s art. Ironically Nolan’s second and third wives are both tacitly implied by art professionals to be implicated in the perceived fall-off in his work, rather than issues within Nolan’s practice itself. Again this casting of blame to malign female influence upon the “true” “genius” – as if women did not fall within the definition of genius – is a trace of art history’s misogynist defaults. Nolan himself disagreed with Sunday’s ambit claim to have single-handedly made and shaped his practice. Cynthia reports him saying in the late 1950s that Sunday’s bitter prediction that Nolan would not be able to paint without her drove him to work energetically for years ahead.

Later Cynthia became notorious as the catalyst for the high-profiled feud between Sydney Nolan and Patrick White. This clash of two titanic darlings of postwar Australian cultural life was vicariously followed by many contemporaries. Cynthia probably became more famous in the last years of the twentieth century for her symbolic role in the feud than for her own achievements. An edited republication of her travel writing in 1994, which focussed on the “travel” and edited out some of her more complex creative and psychological observations, seems to have been a follow on from that curious but tenacious profile. A long passage from White’s autobiography Flaws in the Glassin praise of Cynthia revealed the fact of her suicide,[vi] tactfully, politely avoided in the Australian press at the time in 1976. White chided Nolan’s callous selfishness in marrying too soon and too disrespectfully after Cynthia’s death. Nolan struck back, painting unflattering caricatures of White. Whilst the public feasted upon the scandal, White’s unconditional praise for a fellow creative, relatively rare as his own aesthetic needs and imperatives tended to dominate his outlook, passed unheeded as a measure of Cynthia’s impact as writer, curator and art advocate.

Portrait of Cynthia Reed smoking 1945, gelatin silver photograph, collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, gift of the Estate of Margaret Michaelis-Sachs 1986, photograph: Margaret Michaelis.

Resisting easy pigeon holing, Cynthia is no obvious and easy heroine. She was prickly, changeable, elitist, unable to tolerate those whom she regarded as fools, and recognised and “called out” the legions of the vapid and conventional around her. Her life was overshadowed by a range of complex physical symptoms and health issues. Although it is tempting for the biographer to suggest that some of these illnesses were psychosomatic, in the late 1950s the enigmatic ongoing malaise that dogged her life was given a dire and unequivocal diagnosis of tuberculosis. Happily for Cynthia, by the mid twentieth century this disease was able to be successfully treated.

Historiographically one could liken her to Wallis Simpson, an older contemporary who outlived Cynthia. Unconventional and un-bland Wallis raises complex emotions in her time and to this day, especially due to stories of her dominating her husband, a direct resonance with public accounts of Cynthia. Amongst her contemporaries Wallis elicited divided opinion, considered to be ugly by expected standards, yet unequivocally modern and progressive in her taste and style. Wallis’ gift was to gender the energy of modernism as distinctly feminine and recast femininity in the symbolic universe of the modern as non-abject. The modern woman, as Wallis demonstrated, could operate as purposeful and mature rather than as the fey, wild child beloved of the surrealists.

In an Australian milieu, Cynthia impacted in a similar manner during the early 1930s, and offered the same extension of the feminine image of options for public self presentation. Cynthia was more concurrently riven with self-doubt than Wallis (or Sunday for that matter) and over a decade and a half subjected herself to an ultimately fruitless and humiliating series of attempts, on three continents, to become a film star. Her efforts encompassed plastic surgery as well as acting classes and unsuccessful screen tests. This quest was itself a perverse engagement with popular modernity – despite having proven herself as a game-changer in high-brow modern art and design – and prefigures the current politicised understanding of agency, appearance and extreme actions such as body modification and eating habits. Finally Cynthia found a new confidence in rejecting conventional glamour and turning her back on fashion, aiming for practical monastic simplicity of dress, and adopting the Mao suit years before it was widely fashionable outside China.

Melbourne Books’ recent publication of M.E.McGuire’s austere, restrained, pared-down biography of Cynthia Nolan provides a much-needed full length study of this remarkable woman.[vii] The modest inflection of the narrative evokes the disciplined aesthetic favoured by its subject. McGuire’s sparse yet poetic prose focuses on Cynthia’s long and varied career prior to her marriage and her wide cultural knowledges, as if to exorcise the dominance of the White-Nolan feud and vampiric metaphors in remembering Cynthia. The cohesive presentation of the chronology, the detailing of Cynthia’s experiences in the 1920s and 1930s make the biography a must-have extension to the known literature on the origins of modernism in Australia.

Undoubtedly it offers a fresh perspective on the Heide story. Whilst John and Sunday Reed, Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and their associates devoured foreign literature and magazines and thus doggedly constructed their knowledge of progressive culture at second hand and by dint of their own ferocious intellects and energies, Cynthia had lived for extended periods in France, Britain, Germany and the USA observing avant garde culture including art, classical music, interior design and theatre, at its source from the late 1920s onwards. She had also been conversant with global political developments, living in the twilight of the Weimar Republic, when the Nazi Party’s presence, demonstrating, harassing and handbilling on city streets, was already unchecked. Equally her profile in early 1930s Melbourne was high after her return from her first overseas trip. The social pages charted her activities in a state of befuddled adoration; if she perplexed the conventional, Miss Reed was altogether chic, modern and novel. She soon captivated the most cosmopolitan and progressive minds of 1930s Australia, including the Evatts and the Caseys. McGuire handles her source material with a dry wit that evokes the períod milieu.

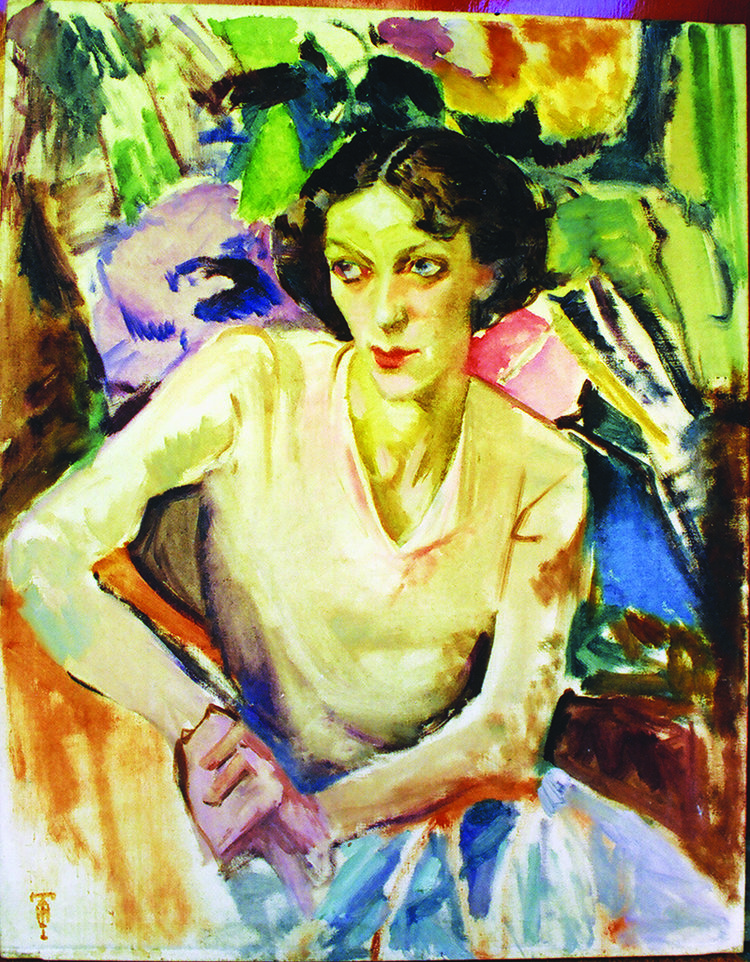

Isabel Hunter Tweddle, Portrait of Cynthia Reed c1933, oil on canvas 92.0 x 71.7 cm, Collection Jinx Nolan.

Cynthia’s striking letters from the Reed archive are rightfully quoted at length and form the backbone of McGuire’s interpretation. These letters alone should assure Cynthia a stronger place in the public canon. Her writing reveals Cynthia as culturally and intellectually the equal of her famous brother and sister-in-law. Filled with engaging unexpected metaphor, bordering on the surreal, and constantly causing the reader to engage with objects and events in a fresh and unconventional manner, the letters belong to the “aesthetic” of Heide and its unbroken continuum between personal expression and progressive, unconventional creative formalism, where art is life. They are also an important Australian exploration of modernism via the written word. Cynthia’s own papers in the Australian National Library, still embargoed until 2021, will undoubtedly offer fresh primary sources around the Heide circle. Certainly there are also “missing” documents around Nolan’s art deposited there. The lifting of the embargo will be an exciting and significant event for art historians and scholars working on both feminist and Heide/Angry Penguins projects.

Albert Tucker, The Dining Room Table c1945, gelatin silver photograph, 30.4 x 40.3 cm, collection: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, gift of Barbara Tucker 2001.

Throughout her life Cynthia remained committed to a very pure vision of innovation and shibboleth-breaking as the driver of creativity, steeped in the haute modernism of the interwar and mid-century period. She advocated an idea of modernism as rightful and self-evidently predominant that has somewhat receded in the wake of post modernism, cultural diversity and the emergence of popular culture and commercially driven cultures, as being equally worthy of academic attention as high modernism. Her self discipline and self analysis was rare in Australian mid-century culture, and lacking amongst many of her associates. White implied that mediocre contemporaries resented her ability to see through them. This rigour perhaps commended Cynthia to White, as noted, one of her greatest advocates. With her intense loathing of convention, her willingness to endure and explore physical and psychic pain in the name of experimentation and searching for a deeper truth, Cynthia could equally have been a character from one of his novels brought to life. Both White and the Reeds, John and Cynthia, shared a family background of social prominence, landed estates and great fortunes. All three were able to devote themselves to creative experimentation and boundary-pushing because of their families’ economic stability. This overlap also predisposed White to identify with Cynthia.

Photographer unknown, The hallway, Heide c1940, Reed/Heide Photograph Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

Since the 1990s other researchers have also engaged with Cynthia Nolan; most particularly Jane Grant advocates for Cynthia’s importance as an agent of bringing a modernist awareness to Australia. Grant’s PhD, like most Australian PhD’s in recent years, is available online to be read and is a major resource for those seeking a fresh perspective not only on Cynthia, but on the Heide circle and Sidney Nolan.[viii] It is a valuable addition to the bibliography around women and modernism in Australia. Written from a literary history perspective, Grant’s analysis often cuts across familiar art historical factoids with a degree of freedom, as there are less art industry norms to be respected from her positioning as a literary scholar. She has no qualms in looking for imagery about Cynthia in one of Nolan’s least famous and least highly regarded series, the Oedipus paintings. Her PhD covers a longer time frame in greater detail than McGuire’s biography, looking into the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the early period. In the PhD Grant especially explores the nexus of autobiography and invention in Cynthia’s writing, and challenges the widespread assumption that Cynthia’s writing was simply reportage of events. The two biographies are complementary and extend the understanding of their shared subject, rather than mutually cancelling the achievements and integrity of each. Grant talked to a slightly different range of informants than did McGuire and that alone enriches public knowledge of Cynthia. However both women were researching back in the 1990s, when many of Cynthia’s friends and colleagues, even family members, were still alive to be interviewed to fill in parts of the story, and their researches captured much that was not otherwise archivally fixed.

Grant’s perspective tends to emphasise the underlying psychological contradictions in Cynthia’s actions and writings, whereas McGuire tends to read the same elements in terms of choice and agency. For McGuire, Cynthia’s evasions and sudden shifts of directions indicate radicalism and intent, not failure of initiative, and are accepted on face value. Conversely Grant suggests that the often vastly different phases of Cynthia’s life and work are triggered by her underlying psychological frailty and the inevitable surfacing of cyclic issues that remained unresolved across the decades. Grant’s approach is perhaps more conventional than McGuire’s, and can be considered to follow on from the Australian literary and academic unease with modernist, highly-wrought, non-social realist novels such as those by Hal Porter, Adrian Lawlor and Eve Langley as well as by Cynthia, and de facto accepts the current obscurity of such writing as an accurate calibration of its status.

However McGuire and Grant both point out unequivocally where first rank cultural players previously have belittled or misrepresented Cynthia. The precision of such critiques and the evidence that is mustered in favour of Cynthia raises questions as to how curatorial and academic practice has accepted these partial and lacking views as the industry standard. Both scholars establish the rigour and credibility of Cynthia’s creative and modernist vision outside the conventional scholarly and curatorial placement of her as a peripheral and servile figure, merely the accessory or handmaiden to others’ creativity. Their quest is valid and McGuire and Grant set out persuasive arguments.

It is typical of the often siloed and competitive vision of Australian cultural and non-fiction publishing that at first glance there does not appear to be much interaction between Grant and McGuire’s dedicated and careful investigations and Nancy Underhill’s comprehensive and iconoclastic 2015 biography of Sydney Nolan.[ix] All these projects were unfolding over much the same time, but the less high profiled scholars’ work is somewhat unfairly sidelined. Also as it is centred upon a male figure, the weight of public prestige and media publicity machines sits more favourably upon Underhill’s book. Underhill’s conclusions about Cynthia’s talent and perspicacity, and her driving much of the foundational values of the Heide legends, the triangulated relationships, the engagement with radical politics and culture in the early 1930s are parallel to Grant and McGuire’s. Underhill ascribes much significance to Cynthia’s professionalism and judgement which substantially shaped and guided Nolan’s high level of fame in the mid 20th century, as well as feeding into nascent Heide cultural ambitions in the early 1930s. Cynthia is defined as both highly influential and yet barely known, but restored to her position of significance within Australian culture in Underhill’s treatment of Nolan. McGuire and Grant rightly put Cynthia at centre stage. It is to be hoped that their revisionist scholarship will create a permanent rethinking of the woman who so greatly expanded the cultural options and vocabulary not only of Melbourne, but via Heide the whole of white Australian settler and immigrant culture and, via her husband. the imaginary of post-war Britain as well.

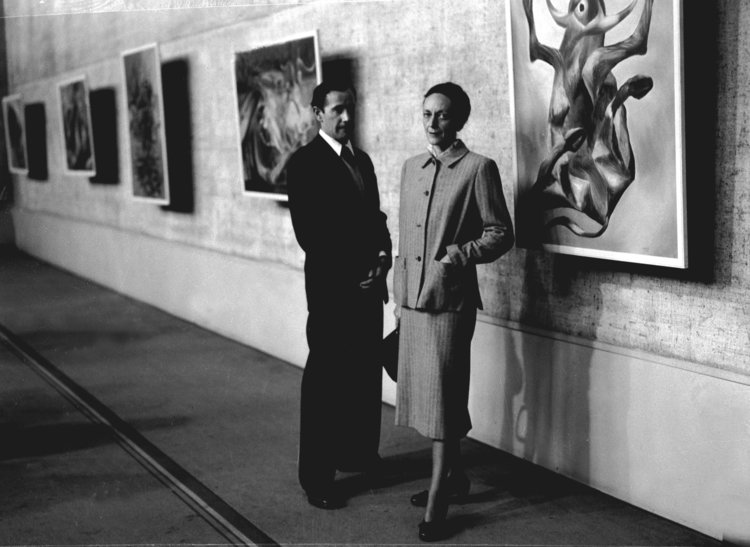

Sidney Nolan and his wife Cynthia 1953.

[i] Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller Awakening: four lives in art. Mile End, South Australia Wakefield Press 2015

[ii] Lesley Harding and Linda Short Those Who Made and Those Who Saw: Portraits of the Heide Circle.Bulleen, Victoria: Heide Museum of Modern Art 2007

[iii] Gaynor Cuthbert Paintings from Paris : the life and art of Moya DyringKerrimuir, Victoria : Rose Library Publications 2014

[iv] Jane Grant Life and work of Cynthia Reed NolanPhD Thesis University of Sydney 2002 p 28 https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/1157

[v] “[t]he dangerous idea of Curatorial Malpractice” Finding The Fieldposted By Natalie Thomas April 11, 2018 In Australian Art https://nattysolo.com/2018/04/11/finding-the-field/[viewed July 2018]

[vi] Patrick White Flaws in the Glass: A Self Portrait. London: Penguin 1983 pp 253-257

[vii] M.E.McGuire Cynthia Nolan: A Biography. Melbourne: Melbourne Books 2016 http://www.melbournebooks.com.au/products/cynthia-nolan

[viii] Details of Jane Grant’s thesis https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/1157

[ix] Nancy Underhill Sidney Nolan: a life. Sydney, NSW New South Publishing 2015