What is the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art?

Whilst known to art curators, academics and art professionals since the later 1980s, the Cruthers Collection was first presented in depth to the public at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts during the National Women’s Art Exhibition in 1995, during a national celebration of women’s art in multiple public art spaces across Australia. Yet this remarkable public collection, unique in Australia, is still unfamiliar to many general art lovers. The strong popular interest in early Australian women’s art – that has at times eclipsed art professionals’ support of women artists over the past forty years – suggests that the collection will grow a far wider fan-base once it is better known.

Michelle Nikou, No vacancy 2011, powder-coated ceramic, neon, Parker table, electrical components, dimensions variable, Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Courtesy the artist, photo Christian Capurro.

The family started collecting art in the early 1970s but since 2007 the collection has been a public one, given by the Cruthers family to the University of Western Australia, after discussions with regional and municipal councils failed to secure a commitment to a permanent home and stand-alone museum of Australian women’s art. The plan is ultimately for the collection to have its own home within the university. Already the collection at the University of Western Australia is the largest stand alone public collection of women’s art in Australia. The earliest pieces are by Ellis Rowan from c 1880s and Clara Southern from c 1890s, and new work is still purchased such as the important sculpture No vacancy 2011 by Michelle Nikou, which recently featured in her survey at Heide Museum of Modern Art, and touring through to 2017. Self-portraits are commissioned from living artists such as Sangeeta Sandrasegar and Sera Waters. Over the years approximately 600 artworks have been donated by the family, with more to come.

The collection has its own small dedicated gallery within the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery on campus, where a series of exhibitions from the collection are presented, in some cases augmented with borrowed or commissioned works. These exhibitions are curated by Gemma Weston, who is employed at the LWAG to support the collection as a physical entity. Moving to a public collection has extended the range of media that could be collected with an increasing component of sculptural pieces and installations that would have been harder to fit within a domestic building. Digital printmaking and photographic imaging and also the return of “craft” into fine arts since c 2000, further emphasised by the recent trends of “new materialism” in the second decade of the 21st century with works in responsive and mutable media such as textiles and wax, also are expanding the range of works, as there is a return to focussing on process and intrinsic qualities of surface and substance.

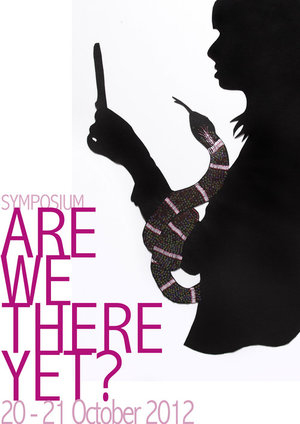

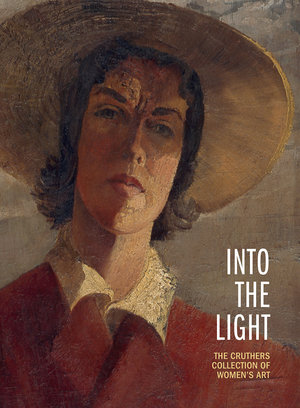

A major survey exhibition Look. Look Again covering the whole timespan of the holdings was presented in 2012 at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, together with a symposium on women’s art practice, Are We There Yet?, organised by the Cruthers Art Foundation. The symposium represents an important component of the whole Cruthers project as the mission is not just to accumulate artworks and build the collection, but to proactively encourage discussion about women’s art. Debate can range from the specific qualities and experiences bound up with women’s art practice to public culture’s blind-spots around endorsing and celebrating women’s art-making. There is a small online presence via the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery and earlier exhibitions are searchable through the gallery’s past exhibition archive. The Cruthers Collection shows are clearly identified within the program for each year. Illustrations of many works from the collection can be found in the two publications featuring the Cruthers Collection, In the Company of Women 1995 and Into the Light 2012, and many will be featured on this blog in months to come. Another overview with illustrations may be found on the Cruthers Art Foundation website.

Symposium Poster: Are We There Yet?, The University of Western Australia, Perth, 20-21 October 2012, commissioned self portrait by Sangeeta Sandrasegar.

Cover of Into the Light – The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, University of Western Australia Publishing, 2012, pp 130.

Given that so many Australian art collections aim to be blueprints of each other, marking “excellence” by including the same range of well-known artists, the Cruthers Collection stands out even more. In 1991 the late Associate Professor Joan Kerr then at the University of Sydney believed that the great Australian collection of women’s art was a dream that was not realised, yet that collection was quietly being assembled on the west coast, even as she aired her dissatisfaction with the contents of Australian public collections. Two areas stand out as featuring a particularly strong representation. Best known are the holdings of early modernism from the 1920s to the 1940s, where women are now recognised as making a highly significant impact upon Australian art. Many works from the Cruthers Collection have been loaned to exhibitions in major interstate public galleries featuring modernist women. A second strength of the Cruthers Collection is art of the 1980s. There is a particularly comprehensive representation of third wave feminist artists, and some of the first women artists to achieve a high profile in the post 1960s contemporary art market, including Vicki Varvaressos, Rosalie Gascoigne, Susan Norrie and Narelle Jubelin alongside some of the key artists exploring Indigeneity, identity and feminism from a contemporary art perspective across the 1980s and 1990s such as Tracey Moffatt, Fiona Foley and Judy Watson.

Another nationally important feature of the collection is the series of self-portraits, which now number almost 100. Whilst not encyclopaedic, they cover a timespan and selection of artists that is unmatched by any other collection of female self-portraits in Australia. They range from the austere and subtly subversive c 1895 self portrait of Cristina Asquith Baker, which unflinchingly includes her damaged right eye, to contemporary commissioned self-portraits. In many cases the self-portraits are matched with significant works by the featured artist. Collecting a self-portrait and representative examples by the same artist was much favoured by Lady Sheila Cruthers. When the collection was in the family home, works by particular artists were often hung in close proximity in a “salon hang” with the self-portrait in a prominent place, as documented by photographs of the time. As well as self-portraits there are women artists’ portraits of siblings such as those by Clarice Beckett and Portia Geach and also images of family members and domestic life such asHelen Grace’s series of images of Christmas Dinner. There are several significant extended caches of works by a number of artists, most notably those of Joy Hester, Narelle Jubelin, Susan Norrie and Julie Dowling.

Cristina Asquith Baker, Self Portrait c1890, oil on canvas, 45 x 36 cm (oval), Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia.

Works on paper ranging from modernist relief prints of the interwar period to works from the print-making revival since the 1950s, form a substantial subgroup. Rare ephemeral protest and political feminist screen-prints from the 1970s and 80s are another focus of collection, as they have often been discarded and destroyed over the last four decades, not being considered worthy of public memory. Often screen-prints were simply functional as much as aesthetic, used to catalyse support for particular meetings or fundraising and lobbying drives, and discarded once the event or campaign had passed. The current exhibition of Kelly Doley’s recent series Things learnt about feminism is both a homage to and an update of this quintessential feminist artform. A series of works feature bright coloured cheap paper and catchy slogans. Sometimes the words are obvious clichés of motherhood statements and motivational catchphrases, others in the set resonate back to historic moments of feminism and in some cases they swerve more into a more surreal and enigmatic textual poésie concrete mode.

Installation view: Kelly Doley, Things Learnt About Feminism #1 – #95, ink on 220 gsm card, 52 x 60 cm (95 pieces), CCWA 956 © Courtesy of the artist. Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, UWA, 8 October-10 December 2016.

Western Australian artists from both settler and Indigenous cultures indicates the vitality of an art history that was in the mid 20th century generally overlooked in east coast-centric models of history writing and curating. The work of the Tasmanian Edith Holmes equally represents less familiar aspects of modernism, as does the work of Hobart-based impressionist Mabel Hookey for the “landscape tradition” in Australian art. Likewise ex-patriate artists such as Sheila Hawkins and artists who moved between Australia and New Zealand such as Maud Sherwood and Helen Stewart also outline a non-standard and multi-layered historical thread. From the 1970s onwards the Cruthers family has been alert to artists who were working on the margins of the accepted narrative, or who had small but impressive oeuvres or careers that did not follow a straightforward path or the clichéd model of a logically built up reputation.

Despite the diversity of outlooks and approaches more apparent since the 1990s, particular themes persist throughout the collection: the female image and perceptions, commentaries on domestic life, families and relationships, both loving celebrations and acidic deconstructions of gender roles and expectations, commentaries on identity and the changing experience of Australian life or being in Australia. A number of works such as Grace Cossington-Smith’s Dawn landing 1945 and Cristina Asquith Baker’s view of the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne engage with public life and politics. Ann Newmarch’s screen-prints address female absence from the public arena and the pressures of control and trivialisation that are applied to women’s lives. Whilst the collection is famed for its avant garde pieces and for tracing a revelatory and interventionist position of women artists exploring new practices, there are some attractive conservative still lives and tonal paintings, and self-portraits by academic artists as well as neo-classical formalism from Nora Heysen and Freda Robertshaw. Another less familiar history that the collection maps is women artists’ important role in developing abstraction in Australia from the 1950s onwards from Margo Lewers to Angela Brennan, and the very characteristic mid 20th century interest in combining landscape and abstraction via Lina Bryans and Carole Rudyard.

I was intending only to write an overview of the contents and range of the Cruthers Collection, but the last few weeks have thrown up some remarkably open and hard-hitting discussions about the ongoing lack of visibility of women’s art in Australian public collections. Given that it is four decades since the emergence of the women’s movement in Australian art c1974-1975 and those four decades have witnessed a rapid increase in unequivocally successful and respected contemporary women artists, there has been a lack of corresponding institutional validation of this generational shift and the four decades of female art-making. No longer personal complaints, these discussions about the measurable inequalities in visuals arts in Australia have been aired in highly visible mainstream media such as ABC Radio and The Guardian newspaper. Partly triggered by The Countess Report (funded by the Cruthers Art Foundation) as well as the outspoken Natty Solo Blog, public disaffection for the constant parade of male artists as featured in blockbuster exhibitions, has finally received some unequivocal and well directed attention. Criticism highlights the unrepresentative nature of the focus of fine arts sense making, as opposed to the expectation in such sectors as health, education, government, from local to federal, as well as national sporting organisations, that the current actual make-up of Australian society shapes the public face of those institutions, which are assumed to speak to and reflect back the images and aspirations of many sectors of a diverse public. At the same time art institutions also have to factor in industry-specific peer-group concepts of what is excellence and what is regarded as a meaningful or relevant aesthetic experience, and that expectation has tended to justify the closed loop of safe and known curatorial choice.

Recent discussion has drawn attention to the repetitive nature of public gallery exhibitions and collections in Australia, particularly in terms of the highly sponsored and elaborately mounted and promoted exhibitions at state galleries and the National Gallery of Australia. Public symposia such as that held by NAVA at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne are also interrogating these absences of a significant sector of the art-making community within public exhibitions and career-making opportunities, and why these inequalities are judged to be acceptable within the industry, despite grass roots dissatisfaction.

So the Cruthers Collection can be read not just as something to enjoy and explore, but as political and a dissonance to this collusive pattern of marginalising women artists. A non-standard collection, when so many public collections across the country are close mirror images of each other – with minor differences begotten only by budget and availability of artworks – is a vital point of cross reference. A collection that is not the same as the others indicates that curatorial choice and policy can look different if the opportunity to think outside the box is taken up and run with. A collection like the Cruthers Collection can be an educational tool, reminding the public and researchers about less familiar artists whilst being itself a change-agent, via the stimulating shifts of perspective that alternative viewpoints may offer.

It can also be, via its exhibitions and this blog, potentially an active participant in these ongoing discussions and debates.