Into the Light: Recovering Australia’s lost women artists 1870-1960 is Sheila’s national research project to collect data about women artists in Australia. One such artist was Sydney-based Elaine Coghlan, whose self portrait was recently purchased for the Into the Light acquisition fund. In this blog Bella Chidlow writes about the work of conservator Anne Gaulton as she unravels the material history of this small painting and restores it to something like its original condition. Anne Gaulton’s own reflections form a fascinating response to her work. The blog concludes with a stimulating essay by Juliette Peers on Elaine Coghlan, the possible reasons for her invisibility in Australian art history and the challenges of reintegrating unknown artists into our art history.

Elaine Coghlan, Self portrait at easel, c1917. Photo Jenny Carter.

The conservation of Elaine Coghlan’s Self portrait at easel c1917. By Bella Chidlow.

Anne Gaulton is one of the most proficient and experienced painting conservators working in Australia today. She began her studies in an art foundation course at City and Guilds London Art School in 1977, followed by a Diploma in Conservation of Easel Paintings at Gateshead Technical College from 1978-1980. She then studied Conservation of mural paintings at the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) in Rome in 1983, then an Honours degree in Visual Arts from Sydney College of the Arts from 1990-1994.

From the 1980s Anne was paintings conservator for the Cruthers family collection, part of which later became the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art. Her research-based practice was ideally suited to a collection which sought to purchase artworks by little known or undiscovered women artists to preserve them for posterity. The collection was gifted to the University of Western Australia in 2007 and now numbers over 700 works.

Conservation involves tracing back the history of an object or artwork through its visual indicators to understand the original intention of its creator, in order to restore it to its original state as much as possible. Before she touches any artwork, conservator Anne Gaulton researches the artist, the time period and the materials used to gain an understanding of why and how each mark was made, which helps her conserve and restore the art works to their full potential. Keeping the artist’s intent in mind throughout the process is important, as is understanding what has happened to the piece in the years since its making. Clues in the painting’s surface and construction can help Anne piece together the history of the object.

Anne examining the painting under ultraviolet light in semi-darkness to reveal any over painting which fluoresces under the ultraviolet light. Photo Bella Chidlow.

Elaine’s portrait reads immediately as a remarkable exercise in restraint; as well as her restricted, almost monochromatic colour palette, she has demonstrated discipline in its application, forming a delicate image in a few considered brushstrokes. The small size of the painting is emphasized by the expertly applied paint; thick, deft strokes capturing how light falls on the folds of fabric. In her condition report Anne notes that “paint layers have been applied quickly and vigorously so that the brushstrokes are integral to the image.”

Anne determined that the wrap-around brown dust coat and easel suggest this little work was painted in an art school setting, and that the monochromatic paint scheme is likely to have been an exercise for the students. In her process of inpainting as part of the cosmetic treatment, Anne realized there is a very limited palette of earth colours present: yellow ochre, red oxide, raw umber, burnt umber along with black and white. She noted: “One can see that the artist is a very proficient painter as this would normally result in drab mixed colours in some hands (especially mixing in black to the reds and yellow ochre to the pinks/browns) but she has managed it beautifully.”

The portrait in raking light with partial removal of retouchings. Photo Anne Gaulton.

The artist’s face is a delicately formed study of colour; the viewer gets the sense that she sat in front of a mirror and translated what she saw onto canvas. The paint has been cleverly applied so that two or three colours are present in each brushstroke; this is an impressionist technique known as ‘broken colour’, which refers to the effect of blending colours optically rather than on the palette. Anne notes that “the artist has also been so restrained that after the spontaneous brushwork she has not gone back to make any changes or retouching i.e. the spontaneity of the brushstrokes is left undimmed.”

Elaine’s restricted colour palette is consistent throughout her career; her 1929 entry to the Archibald Prize was composed of shades of brown, grey and white, capturing in minimal strokes her sitter ‘Tiger’ de Clonsay. In the mid 1920s Coghlan studied under Lawson Balfour at the Sydney Society of Women Painters, and she exhibited a portrait of him in their 1926 exhibition. The Daily Telegraph of 29th April 1926 noted “One admires the adventurous spirit of E. E. Coghlan, who contributes a clever study of Lawson Balfour.” She has indeed skillfully captured the light falling on Balfour’s features in a few deft marks, expanding her usually muted colour palette to illustrate the warmth of his complexion.

Coghlan’s self portrait has pin holes in the top corners indicating the canvas had been pinned up to be painted. Initially Anne suspected Coghlan herself had cut the work down and adhered it to cardboard many years after painting, but it seems likely that the cutting down and adhesion to a board was done by a restorer. Prior to its adhesion to the board, the painting appears to have been bent or rolled as the paint and ground layers show lines of cracking in patterns that indicate these mechanical processes. The artwork seems to have been stored in damaging humidity levels up until this point, as it also had to be cleaned of mould/fungi. The cleaning solution used could have been an anti-fungal chemical compound such as Dieldrin. The drastic cleaning process may have exacerbated the flaking of the paint and ground layers. Then, the work went through a process called marouflage, where the canvas is cut down and adhered to a rigid support, a common technique in the 1970’s to preserve canvases when conservation treatment was still in its infancy. The marouflage process can be undertaken using a vacuum hot table, where the painting is laid face-up on top of the rigid support using the heat and vacuum elements to seal the painting/support sandwich. Anne can see that this was “done with little care” through the number of paint flakes left sitting on the painted surface and because the highest impasti of the dust coat have been melted and flattened. The work was presumably flaking and lifting and so this necessitated some treatment, but “marouflage was not the correct treatment, just the easiest one.”

The work has had a second intervention since the somewhat careless 1970’s treatment, most likely a brief restoration before its auction sale when it was purchased as part of the Into the Light acquisition program in 2019. For presentation at auction many of the small losses of the paint layer had been retouched using oil paint, which was easily removed with petroleum spirits when Anne started to conserve the work after examination and photography. Thus began the third period of intervention in 100 years for this painting. After removal of the oil paint retouchings, which extended beyond the borders of the small losses, Anne could start to see the image a little better. The removal of the oil overpaint started to reveal the fine qualities of the painting and make reading of the image easier.

Removal of oil overpaint (detail). Photo Anne Gaulton.

Detail of portrait in raking light after retouching removed. Photo Anne Gaulton.

Coghlan’s portrait comes in a frame made in the last twenty years, a thick faux gold construction intended to look opulent and classical. It has been treated with acqua sporca (‘dirty water’ in Italian) to make it look antique but Anne dates it to about 1990. She notes the frame provides “adequate support for the work although it may not be aesthetically suitable.” While we know this was not the choice made by the artist, the frame is now part of the object’s history and the conservator must not be quick to replace a frame, whether new or old. When taken out of the frame for treatment, the canvas on board was revealed to have a slight convex warp but has good adhesion of the canvas to the board.

The portrait was purchased in this frame which we believe dates from c1990. The decision was made to retain this frame as it is now part of the object’s history. Photo Jenny Carter.

The process of conservation is like peeling back layers of the past, and so much can be discovered by understanding the history of an art object. Anne’s initial condition report judged this to be a brief conservation job; consolidate the edges, surface clean front and back, and cosmetic work on pin hole losses and at the lower left corner. Once she started investigating the surface she discovered the previous retouching job, as well as the marouflage and anti-fungal treatments this small painting has endured.

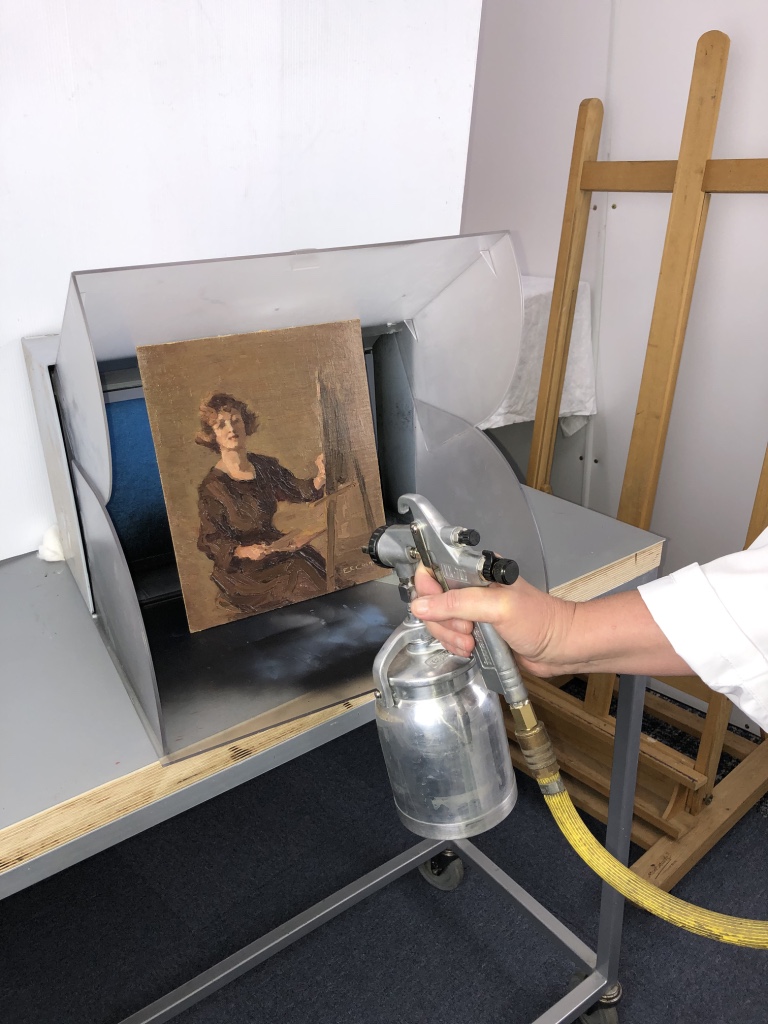

She also initially reported that it had never and should not be varnished, deciding it was an important stylistic choice by the artist that was consistent with her use of the painting materials. This opinion has changed through the process as Anne discovered the extent of the dryness of the paint and ground layers as the result of the anti-fungal treatment, and realized that the dark colours of the work could never show to advantage without varnishing. Just as important, under close examination the fine lines of rolling and folding of the canvas were showing up as white, powdery lines criss-crossing the dark paint layers. A gloss varnish was applied with a brush prior to inpainting, which is the cosmetic part of conservation treatment, where conservation mediums are mixed with dry pigments to match the existing paint layers. After the cosmetic work was completed the painting was sprayed with varnish. It is a glossy finish that shows up the liquid and spontaneous brushstrokes that make this work so appealing. These new layers are made from conservation grade materials that should not degrade or yellow over time and that remain removable in mild solvents.

Application of spray varnish to the painting during conservation. Photo Anne Gaulton.

The experience of working on this piece seemed more intimate than her average conservation job. She said: “It has quite a history for a small work. It managed to look good despite all the bad things that happened to it. The process of reflecting so intensely on the work and reading texts from four different perspectives is not something I normally have the time to do. This job in particular with its smallness, its quality and the opportunity to reflect on it in depth made me realize once again how fortunate I am to spend so much time with a work. The National Gallery of London says that each viewer spends an average of 16 seconds with each work, but I can often spend a week. Some works don’t hold up to be looked at for that long, but this little work remains interesting. When you consider what this poor little work has been through, it is a marvel that it looks so good. It is down to the quality of the work I think”.

Bella Chidlow is a 23 year old artist who grew up in the Blue Mountains and now lives and works in Wollongong, south of Sydney. Since completing her Bachelor of Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong she has interned at the Sheila Foundation and the magazines Art Almanac and Artist Profile in Sydney.

Notes on the conservation process. By Anne Gaulton.

I think the monochromatic paint scheme is likely to have been part of an exercise set at art school for the students. The large easel and the brown wrap coat make me think this is an art school setting.

Inpainting the work made me realise that there is indeed a very limited palette of earth colours – plus white – that has been used. This would be a typical exercise for a painting class, even in contemporary times. I think the pigments used are yellow ochre, a warm rich red oxide, raw umber and burnt umber plus black and white. So maybe the exercise was five earths?

One can see that the artist is a very proficient painter as this would normally result in drab mixed colours in some hands (especially mixing black to the reds and yellow ochre to the pinks/browns), but she has managed it beautifully.

The use of a red oxide mixed with white and yellow ochre is a typical way of making skin tones. Coghlan has picked a vivid red oxide that makes a lively pink when mixed with white. You can see the lively pink on the palette the artist is using.

The artist has mixed the oil colours on the palette and then applied them very quickly to the canvas. The brush strokes are a clever mix of two or three colours put on so that the brush stokes will have another colour at the end or on the sides of the brushstroke. The artist has also been so restrained that after the spontaneous brushwork she has not gone back to make any changes or retouching i.e. the spontaneity of the brushstrokes is left undimmed.

Coghlan’s brushstrokes and colour palette up close. Photo Bella Chidlow.

The paint and ground layers are very dry and brittle. The work appears to have been rolled or bent before the marouflage. The marouflage was done with little care so that there were a number of little paint flakes left on the surface millimetres away from the actual loss. The work was presumably flaking and lifting and so this necessitated some treatment although marouflage was not the correct treatment, just the easiest one.

I think the work may have been marouflaged using a hot vacuum table. The heat and pressure have squashed and flattened the highest points of impasto, which have subsequently been retouched during the last restoration.

I think it is highly likely there are two periods of restoration (rather than conservation):

1. The first intervention which may have been carried out on the hot table during the 1970’s. The work was probably flaking, precipitating treatment. Many of the flakes have been left on the surface after marouflage. There were also fly spots. I don’t think it was varnished. The painting was well and truly dry by the time of marouflage. The canvas was cut with a knife at the edges and put on top of a piece of cardboard with an unidentified adhesive between the two layers, and then put under heat and pressure on the hot table. I don’t think the canvas had ever been stretched before it was cut down. I think it is likely that the canvas was kept rolled after painting and perhaps suffered some folding as well. Very fine white, powdery cracking in the paint and ground layer indicates possible rolling and folding of the canvas.The work had mould or fungi over the surface that was cleaned off before marouflage. It may have been cleaned with Dieldrin, which removes fungus in plant material and which is probably carcinogenic. The anti-fungal treatment would explain the dryness of the paint layer and the uneven harshness of the cleaning. It may have made the flaking worse or even caused it.

2. It seems quite likely that the work has undergone a very brief intervention (i.e. restoration) before the auction when the work was purchased from the David Angeloro collection in July 2019. There were numerous retouchings covering up very small losses all over the work when purchased at auction. It may be that small losses remained after the first restoration in the 1970’s and the owner decided to have the losses retouched before auction. Oil paint has been used for the retouching and this is easily removed with petroleum spirit – the ease of the removal indicates recent work. The retouchings went over the edges of the losses and so reduced the reading of the image.

The work was probably the most difficult to retouch of all the five painting I worked on for the Into the Light acquisition fund because of its spontaneous, mixed-on-the-palette brushwork in the background areas. Each brushstroke is slightly different. As the work is so small but so well painted it was like working on a miniature. Every brushstroke has been made to count by the artist. After the initial varnish of the work – it had to be varnished for a variety of reasons – one could start to see that there is a wonderful and varied pattern of horizontal brush strokes with lovely pink tones here and there for the background, with vigorous diagonal impasti for the body and head, and strong vertical uprights for the easel.

Detail of painting showing the pink tones brought to life by the varnish during conservation. Photo Anne Gaulton.

What a proficient work and most likely painted at age 20. When you consider what this poor little work has been through it is a marvel that it looks so good. It is down to the quality of the work I think.

I feel sorry for these women artists whose work has been purchased for Into the Light. When I look at the works considered to be second tier, I think some of the artists didn’t have enough time to develop their voices and their technical capacity, or what voice and capacity they had was lost through age and adversity.

Anne Gaulton is an experienced paintings conservator undertaking treatments as well as the conservation management of collections. She is well trained in museology and has undertaken work in many of the Sydney museums and galleries, working privately since 1990.

Elaine E Coghlan (1897-1989). By Dr Juliette Peers.

Elaine Coghlan’s lively and confident small self-portrait engages the viewer at once. Buoyant and direct, this charismatic artwork sits above the legions of 20th century Australian impressionist and representational paintings that, when commerce is not in a lockdown, trade monthly or weekly at auctions across the country. Yet the painting is not simply a delight for the eye: behind the painting stands the story of a notably successful and versatile Sydney artist, who is now unknown to all except the most dedicated researchers into obscure art histories, given that it had been in the private collection of David Angeloro, who presented it in the anthology Heritage: The national women’s art book (1995).

Detail of portrait after conservation. Photo Anne Gaulton.

In the 1920s/1930s Elaine Coghlan explored the wide range of opportunities that Sydney offered emerging artists between the wars, without contributing to debates around modernism. The latter have traditionally been the frame of reference for both curators and historians to place an artist within the repertoire of public memory. Thus, Elaine Coghlan has substantially escaped the attention of art professionals focussed on the emergence of modernism in Australia

Coghlan was one of the younger committee members of the Sydney Society of Women Painters in the 1920s and stayed with the group after it became the Women’s Industrial Arts Society in 1935. This shift in name and profile acknowledged women’s increasing participation in commercial and public life in New South Wales, a process that Coghlan stood witness to. She also showed with the Painter-Etchers Society, the Australian Art Society and the Royal Art Society, was selected for the Archibald Prize several times and held small solo exhibitions in the 1930s. Also she received commissions for etched bookplates, a highly popular subset of printmaking during the interwar years. In the context of art making in Sydney at that date, these were all expected benchmarks of success. Several of her surviving portraits of other well-known Edwardian and interwar Australian artists, both male and female, suggests that Coghlan’s colleagues saw her as a co-professional and document her place within a network of artists. The major interwar collector of Sydney art, Howard Hinton, bought and gifted her work to the Armidale Teachers’ College (now located at the New England Regional Art Museum), another clear indication of her reputation in the interwar period.

Far from being marginal, Coghlan’s working life informs later generations about forgotten details of creative experience in early and mid 20th century Sydney, outside of modernist circles. Many of these artists’ lives have been documented by the Sheila Foundation’s project Into the Light and Coghlan substantially shared experiences with a generation of peers. Sydney’s artistic life in the period 1910-1960 was never as clearly trajectoried as that of Adelaide or Melbourne. Whilst artists in the latter two cities enjoyed straightforward career paths, in Sydney pre 1950 there were two, later three, rival art schools, and at least six major art societies for non-contemporary work, even though commercial dealers and smaller art spaces were limited. Coghlan studied with Dattilo-Rubbo and James R. Jackson’s Royal Art Society school from 1919-1923, which set her up her alignment with the RAS itself.

Like many women artists in early and mid 20th century Sydney (more so than Melbourne or Brisbane), Coghlan came from a socially prominent family. Her father was the NSW Attorney General, having himself risen to gentility from humble Irish Australian origins via a stellar career in the public service. Elaine Coghlan lived and painted on the north side of the harbour, which was, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, a cluster of artists’ homes and studios, and a major hub of art activity. Many of her landscapes depicted Sydney Harbour. Interwar Sydney witnessed a large cohort of academic, late impressionist landscapists and portraitists, to which Coghlan belonged. With the coming of contemporary art and the withering of many of the previously robust art societies by the 1960s, Coghlan’s art became less visible in Sydney, although she was discussed in the press as late as the 1950s, after three decades of working in public.

Yet Coghlan’s self-portrait offers far more than the solid-enough documented backstory of her career. Amongst the collection of women’s self-portraits in the Cruthers Collection, relatively few show women as working artists, with the exception of Alice Bale’s early and authoritative vision of herself in formal Edwardian dress, standing at an easel. Most of the Cruthers Collection portraits capture a more intimate vision of the self, focused on psychological insight and self-scrutiny, even self doubt, or the confidence of a glamorous and assured public self-projection. Coghlan’s work, as does Bale’s, resonates with an older, extremely important tradition of European women artists from the Renaissance onwards, using the image of themselves in the act of painting as an assertion of their professional legitimacy. These self portraits symbolise their right to be an artist and simultaneously record their technical accomplishment. Coghlan’s portrayal of herself brush in hand, seated at an easel, gazing into an invisible mirror, yet locking onto and challenging the viewer as well, directly speaks to this tradition. Edwardian art historical publications such as Walter Shaw Sparrow’s Women Painters of the World (1905), made such images accessible in Australia.

Certainly the rise of the alternative, artist-centric value system of the avant-garde from the mid 19th century onwards increasingly rendered such public assertion superfluous. Yet rather than being a tired, belated and derivative response, the brio of Coghlan’s clear enjoyment of mastering the act of painting carries the viewer with her. Coghlan’s work, alongside Bale’s, ports that tradition not only into the Cruthers Collection, but into the narrative of early 20th century Australian art. Equally it is a reminder of the strongly Eurocentric, Italianate thread within Sydney art making documented through illustrations of lost works in art society catalogues and old newspapers across three decades. European art was made real and personal through the ambiance of the Dattilo-Rubbo studio, where Coughlan studied. Dress and hairstyle suggests a date in the late 1910s-early 1920s, soon after World War I, during her student years.

Coghlan appears not to have followed on from this work. Her other currently known oil portraits are stiffer and more reserved in their handling, sometimes with a neo-classical austerity, sometimes more with a commercial art vibe. However both modes of portraiture were current and accepted in exhibitions in Sydney during the 1920s and 1930s and her deployment of them again indicates her synergies with other artists at that date. Only Coghlan’s watercolour landscapes retain the lightness and agility of touch seen in her early self portrait. However given that currently there is no detailed first hand commentaries from Coghlan and, even with parts of her estate appearing in auctions over the past two decades, understanding of the full extent of her talent and motivation remains provisional and speculative.

Portrait of Elaine Coghlan from The Australian Woman’s Weekly, 18 November 1933. Courtesy of Bauer Media Pty Limited/’The Australian Women’s Weekly’.

Many of us remember the fictitious Ern Malley’s lament that he “had read in books that art is not easy”, but equally art history is not as simple as it may seem at a superficial glance. How do we deal with an outlying artist and an outlying painting? Does the outlying painting act as a positive calibration of the artist’s deserved placement in public narrative, or is it a melancholy reminder of a loss of potential, a failure of will, either due to personal shortcomings or a hostile and sexist social environment. If other pictures from the same hand do not share the same qualities how does that shift any judgement? Is the painting sufficient and appealing in itself as an art historical entity, without further debate? Do the regular templates that we use to order the art of the past unfairly devalue and marginalise an individual artwork? Should we then question both the system and those who accord with it for being more at “fault” than the artwork, and unable to deal with variation from the norm? The writing of women’s art history is neither easy nor fixed. So much of what survives or is buried in newspapers and archives falls into this liminal and uncertain zone, lacking clear peer group auspicing, where there is no authority or precedent to aid decision making and good practice may censor and suppress rather than reveal.

Dr Juliette Peers is an art historian and curator specialising in women’s art. Her publications include More than just gumtrees, on the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors, and Completing the picture – Australian women artists and the Heidelberg era.