‘THE POSITION OF ART IN THE WOMEN’S LIBERATION MOVEMENT IS THE POSITION OF WOMAN IN THE ART’S MOVEMENT’ (1)

Embedded review by Madeline Sarich

Curator Sandra Murray presents the second incarnation of the exhibition entitled Embedded, in celebration of International Women’s Day 2020. The exhibition is on display at Flux Gallery, Perth until 18 July 2020, showing works by Ruby Armstrong-Porter, Claire Bushby, Olga Cironis, Nikita Dunovits-Ferrier, Michele Elliot, Tania Ferrier, E Anne Jeppe, Pam Kleemann-Passi and Molly Werner .

To embed means ‘to fix something firmly and deeply within a mass or material substrate: to envelope or enclose; incorporate or contain as an essential part or characteristic; insert, implant, assign or place’. (2) The exhibition Embedded is composed of nine personal interpretations of the domestic quilt, through which curator Murray highlights nine explorations of the traditional materiality of the quilt, each in turn charting a breadth of personal anecdotes. The wide representation and experience of the nine artists, which spans a wide variety of age and background, allows the exhibition a distinct capacity for relatability for women of many ages and experiences.

Murray’s curatorship of Embedded is guided by nuanced associations between works. A commonality of the works in the exhibition is the cyclical, repurposed quality of the materials from which the quilts are constructed, from Bushby’s use of natural materials, to Nikita Dunovits-Ferrier’s repurposing of the t-shirts she wore in her adolescence, and Molly Werner’s re-use of polyester chiffon remnants that were, in a past life, dance costumes. The value of sustainable practice has become increasingly commonplace: as understanding and awareness of the catastrophic environmental damage which is unfolding globally, and perpetuated by a frivolous attitude and short lifespan of materials comes to light in popular culture, the art world is no exception. In Embedded, there is a reigning intention with the artists to utilise recycled materials and natural products: it is reassuring to see the potency of materials which have existed in multiple forms and spaces.

This cyclical quality of the materials fosters new layers of meaning: many of the works seek to evoke memories and feeling – the re-use of materials builds upon this intention. When something is reused, there’s inevitably an associated personal history: layers of meaning are created when materials hold their own past. Michele Elliot’s work, slip, sleeve, cover, is composed of material (silk, satin, found clothing) quilted together with hair –the collection of which was durational. Elliot notes that the use of hair in her work functions as a material representation of abjection, the body, and liminality. The story, like many of those attached to works in Embedded, is heavy: the work serves as a physical manifestation of Elliott’s response to a homeless woman whom she encountered on her daily commute, making home in the bus stand at Railway Square in Sydney. This liminality between public and private, an ambiguity in belonging, a dislocation, is a feeling that emanates beyond this particular work, and beyond this particular story. On one level, Elliot raises the alarm on the homelessness issue here in Australia, further, she implores a feeling of empathy by reminding us that this disoriented feeling is one that can be imbued by many experiences, encouraging the viewer to empathise on an uncomfortable level, with this story. Liminality and ambiguity are feelings which run through Embedded. Stories of discomfort, in the home, in the self, and as a woman, run through the exhibition, and, I imagine, through women everywhere.

Claire Bushby’s Bushpig, which was commissioned for the show, stands alone at the beginning of the exhibition. The work is delicate in its materiality: silk, dyed with eucalyptus leaves, creates a backdrop fitting for the embroidery of this ‘bushpig’ character. The soft and malleable silk has been transformed with a harsh rigidity; it stands powerful, a talisman for strength against adversity. The contrasting lines of the red thread enhance its violent beauty; it is an image of trauma and deprecation turned into an image of self love – the persona of ‘…a woman who is strong and connected to the Earth’ and herself. Bushpig, resonated strongly for me as a young woman. Having been called a ‘bushpig’ by bullies in highschool, Bushby creates a space through this work to reclaim and reshape this aspect of her identity. The word ‘bushpig’ lends itself to a very grotesque, distorted image of a girl. Bushby highlights the commonality of experiencing this self-disgust, and shame in adolescence which can be carried nonsensically into adulthood. Acknowledging the source of these feelings, melting the disassociation between adulthood and deep-rooted perspectives and beliefs about oneself, which remain from childhood, and then coming to terms with them, is a worthwhile process which Bushpig encourages. Bushby reclaims the bush pig as a powerful character; retrospectively reconnecting with and re-embodying this identity from a perspective of maturity and self-love. Such a process, I imagine, would be very cathartic, a potent form of self-empowerment.

Molly Werner, OVER:UNDER, 2020. Photo: Pamela Kleemann-Passi

OVER/UNDER by emerging Western Australian artist Molly Werner was one of two new works by local artists (alongside Bushby’s Bushpig), commissioned specifically for the Perth iteration of the show. The quilt hangs from the ceiling: the capacity for the viewer to be able to walk around the work, to take advantage of its ethereal nature, is a noteworthy curatorial decision. Composed of polyester chiffon remnants from Werner’s work as a costume technician, delicately stitched together with leftover project thread, OVER/UNDER breathes new life into these discarded materials, bringing together various material histories and forging an entirely new story for the various elements as a cumulative object. The quilt is large, layers of cream and white fabric envelope together: one can imagine, if hung outside it would gently sway in the breeze. The delicate stitching connects the work to Elliot’s slip, sleeve, cover, the thread reminiscent of the hair with which Elliot’s work is held together. The liminal message of Elliot’s work can also be connected to Werner’s work, which, as an object, occupies a liminal space in the gallery. OVER/UNDER feels like a physical embodiment of this liminality, its process of creation and regenerative quality, a practical response to the feeling of ethereality, of occupying a temporary space, of having the capacity to transform, to exist, to disappear, and to reappear. In this sense, Werner’s work is moving: it reminds the viewer of the capacity to reimagine oneself, that harnessing the temporary, the liminal, can birth new histories, can be a process of creation. Werner notes that in the future the quilt will once again be repurposed, forming a new object, continuing the cycle of regeneration and building upon this material history.

The quilt, as an object, is traditionally domestic: it is associated with comfort and warmth. These qualities of the domestic realm are traditionally embodied and enacted by women: the quilt can be seen as a sort of a metaphor for the safety of the domestic sphere. Embedded makes space for the woman (as artist) to reclaim the quilt: the works tend to remove the comfortable, familiar aspect of the quilt, thus subverting, in a very physical sense, these qualities of the object. The objects assert the discomfort and unease that is embodied when these traditionally safe and warm experiences of the home have been disrupted or totally corrupted by a negative experience or association.

This dichotomy is buried within many of the works: objects of comfort become symbols of discomfort, of fear, objects of subversion. In Embedded the artists have physically and metaphorically dismantled the fixed, safe, familiar nature of the quilt, and in turn, they are working to disturb the traditionally feminine associations with the comfort of objects of the domestic sphere. Objects which are traditionally associated with the feminine break out of their expectations, they become grotesque, confronting, the quilt becomes an object of resistance. By virtue of this action, the feminine is liberated from the domestic.

Tania Ferrier’s Angry Underwear is incorporated into an interpretation of the quilt entitled Ms Angry Underwear Quilt which holds a dark story. The underwear in the quilt originated as a part of Ferrier’s Angry Underwear project in the 1980s in which, after witnessing a sexual assault, Ferrier began making angry underwear for strippers in New York City. The angry underwear works as a very direct embodiment of a desire to interrupt and redirect the male gaze: bras and underpants are painted with eyes and mouths resembling sharks, mouth wide open, big teeth, or wide eyes occupy the place of standard lingerie embellishments of a pretty or delicate nature. Ferrier seems to hold an overt awareness of the often sexualising, even demeaning male gaze, and seeks to interfere with this directly. Ferrier reveals a dark history of childhood sexual abuse, and articulates the way that with humour, and courage, reinforced by her experience making the angry underwear, the process of creating the quilt allowed her to look back at her childhood from an empowered, strong position. Ferrier’s work makes the feminine, the ‘approachable’, physically confronting. Its materiality is effective on a metaphorical level. It interrupts and redirects the male gaze.

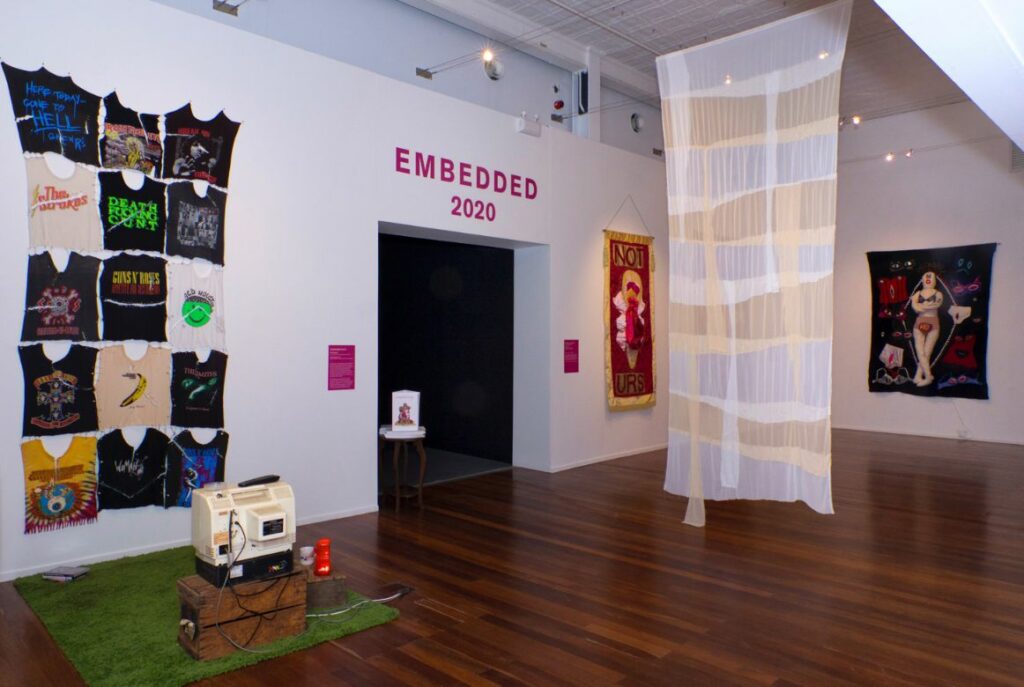

Dunovits-Ferrier’s work, Sweet child o’mine embodies a similar process. The work is composed of a selection of band tees that she wore as a teenager, repurposed into a large ‘quilt’ joined by safety pins, hanging on the wall. Beneath the quilt lies an installation reminiscent of the landscape of a teenage bedroom: shaggy rug, collection of dvds and fuzzy television. The artist seems to find self-acceptance in the creation of the work, by addressing, very directly, events and materials from the past. Similarly to Bushby’s Bushpig, the confrontation of these objects and ideas, relics of the discomforts of adolescence, in retrospect, can foster self-acceptance.

In her 1972 Women’s Art: A Manifesto, Valie Export states: ‘if reality is a social construction and men its engineers, we are dealing with a male reality… let women speak so that they can find themselves, this is what I ask for in order to achieve a self-defined image of ourselves and thus a different view of the social function of women.’ (Export 47) In Export’s spirit, Embedded, as an exhibition, addresses women: an aspect which holds strength and integrity in terms of reclaiming female space in Australian art history. There is a strong sense that the production of these quilts was a cathartic, emotionally charged process for the artists. This emphasis on the process, on re-imagining materials, in such a personal way, is one means by which the works all become by women, and for women. At this moment in art history, a greater recognition of female artists is happening internationally: Embedded addresses the imbalance of women artists in collections and in gallery representation.

Installation view of Embedded with works visible (L-R) by Ruby Armstrong-Porter, Olga Cironis and Tania Ferrier. Photo: Pamela Kleemann-Passi

Sources

- Export, Valie. “Women’s Art: A Manifesto” News Forum 228, January 1973, https://monoskop.org/images/3/3d/Valie_Export_1973_2012_Womens_Art_A_Manifesto.pdf

- Embedded 2020. (catalogue) Sandra Murray, 2020.